Historical fiction and historical nonfiction are interrelated and can be based on the same material. But when an author gets an idea for a new project, how do they decide which route to take? Read about Julia Park Tracey's experience below, and many thanks to the author for her thought-provoking essay!

~

How I Wrote a True Story as a Novel

Julia Park Tracey

I first started writing The Bereaved (a novel) as nonfiction. I'm a journalist by trade, and that means I look for facts and figures and actual quotes and information. I had just finished editing the second of two books called The Doris Diaries, about a teenager flapper in the Roaring Twenties. They were my great aunt’s diaries that I had inherited after she died. I had done a ton of background research, everything from teenagers in society, what were they eating and drinking, cars and technology, social upheaval, medical practices, clothes and fashion, and so on. I wrote a long introduction, several appendices, and indexed both books.

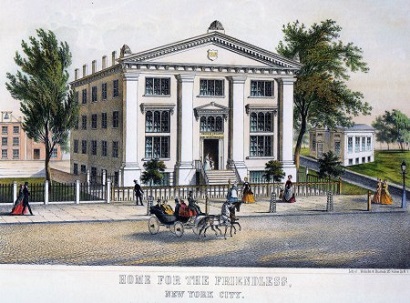

As a journalist and a part-time scholar of women’s history, I fully intended to take the story of The Bereaved—the true story of my third great grandmother and how she lost four of her children to the Orphan Trains, and how she tried to get them back—and tell it as nonfiction. In fact, I was excited at becoming known as a writer of women's history and telling untold stories.

I knew all of the facts of this story. But I wasn't quite sure how I was going to tell it. I laid it out chronologically and looked at the details, and I read several books of creative nonfiction about historical events. I took my outline with me to the Community of Writers at the Olympic Valley in Lake Tahoe and shared it with my group. The other writers gave me a lot of great ideas—for how to write a novel. So did the male leader of my group in my one-on-one meeting.

I was outraged. Are they saying that women should write novels instead of serious history? I spent a lot of time in the next two months raging internally about the misogyny inherent in that idea. But at the same time, I wanted to know what it was like to be Martha Seybolt Lozier.

So I bought some fabric and I bought a pattern for a Civil War dress; I cut it out and started sewing by hand. I sat in that wicker chair by the window and stitched lace and facings and top-stitched. I continued my hand sewing, between bouts of further research into her days and her era, while thinking about Martha and her children.

And as I sewed, I started thinking about all the things that Martha knew.

She knew how a pound of butter felt in the hand. How an old hen’s pulse beat against her fingers before she twisted its neck. How the feathers made a thin wet pop as she pulled them from the cooling skin.

That was the first paragraph that I wrote: Some of the things that Martha would know from living on a farm. And I knew that the language of living on a farm was what informed her character. I kept hearing Martha in my thoughts—what she might think about things and what she might have to do.

Managing the eggs: They need to be wiped but not washed. They’ll keep for weeks, but store them away from onions, fish, the smokehouse.

Ducks rose from the water loud with their honking voices, their clumsy splashing, the rapid beat of wings. How did Canada geese make flight so graceful, while ducks just seemed late and worried and fatigued? Like herself.

I kept writing what I was thinking about. And then when November rolled around and it was time for NaNoWriMo, I took advantage of the thirty days of enforced writing and coughed up a 50,000-word draft. Later, I went back through and wrote it again, adding another 40,000 words. Martha took shape, and so did her children, and so, too, The Bereaved.

Instead of writing in a journalistic style, I was writing a close third person, telling Martha’s story and (gasp) filling in the details that I imagined, that I invented: The color of her hair, her eyes. Her relationship with her in-laws. The terrible thing that made her flee from the farm. And so on—breaking the sacred journalism rule that Everything Must Be True.

I reality, there are many facts I don’t know about Martha. I have not yet seen a photo, if any exist. I found her burial site but not when she died. I have seen her signature but I don’t know her voice or anything she might have said directly. All of my quotes are imagined.

For a journalist like me, that was hard to do—but Martha and her story are worth it.

The Bereaved: A Novel—Historical fiction by Julia Park Tracey; Sibylline Press, August 2023; 270 pages; ISBN 9781736795422. $18.

Julia Park Tracey, a journalist of 40 years, is the author of seven books. Her latest is The Bereaved, historical fiction about a destitute widow who takes her children to an aid society in New York City for safekeeping, but the agency sends them out on the Orphan Train, and the bereaved mother must find her children again (based on the story of her third great grandmother). Find her online, any platform, @juliaparktracey.

I love this story of how Julia brought her character to life. This is what I love about historical fiction. In the words of Jessamyn West, "Fiction reveals truths that reality obscures."

ReplyDelete