In summer 1940, Ruth Gladstone, an English literature student at Girton College, Cambridge, evacuates with her grandmother to the Lancashire village of Martynsborough after an unexploded bomb lands on the campus. While staying with her great-aunt Vera, from whom her Gran (Edith) had been estranged for years, Ruth gets pressed into dreary administrative work and delves into a local ghost story – which she glimpses firsthand.

A young woman garbed in white has been seen lurking around the fields and lanes, calling to mind a tragedy from 30 years before, when a woman’s body was seen floating in a lime-kiln pond on the grounds of Wolstenholme Park, a crumbling old manor.

The story begins as everyone’s already on edge from potential German bombings and amps up the tension with a gothic subplot. Furthermore, Ruth’s seeking an exit strategy from an unwanted engagement to a soldier who writes her embarrassingly crude love letters from overseas, and she worries he’ll come home and expect an impromptu wedding. The stage is set for a tale where suspense and dread build from multiple directions.

What transpires, though, feels more atmospheric than spooky or horrifying; this ghost story is pretty low-key. There is some mystery about whether the white apparition is Elise, wife of Ruth’s coworker Malcolm, a Frenchwoman who became mute and dissociated from the world after a brain injury. From the villagers, depicted (with a few exceptions) as stereotypically insular, emerges the feeling that the evacuees in their midst have stirred up the wraith, but Ruth doesn’t buy that explanation.

On the hunt for a subject for her first novel, Ruth decides to research the history of the hauntings in Martynsborough, which goes over about as well as you’d think. With an occasionally brusque manner, Ruth sometimes feels closed-off and distant, although she does earn the reader's empathy. Her growing rapport with Malcolm makes for an awkward “forbidden romance” scenario, since his wife is very much alive, and it’s unclear how mentally present Elise is.

While all of the mystery threads (including the surprising reason behind Vera and Edith’s falling-out) are sufficient to hold interest, Through a Darkening Glass functions better as a portrait of country life during wartime, showing people’s day-to-day experiences and their adjustments to new circumstances as the war trundles on much longer than anyone expects or wants.

Through a Darkening Glass was published by Lake Union/Amazon Publishing in January 2023; I snagged it from NetGalley. It was also an Amazon First Reads pick last month.

Showing posts with label book reviews. Show all posts

Showing posts with label book reviews. Show all posts

Sunday, January 15, 2023

Tuesday, October 04, 2022

Heather B. Moore's In the Shadow of a Queen introduces Queen Victoria's rebellious daughter Princess Louise

Princess Louise, sixth child and fourth daughter of Queen Victoria, was a trailblazer within the British royal family. Not only did she marry a commoner, a highly unusual circumstance at the time, but she was a talented sculptor who pursued a career as an artist, enrolling in the National Art Training School and attending classes – when her schedule allowed – alongside ordinary people. But getting her devoted Mama’s permission took work. So did essentially everything else in her highly regulated, scrutinized, and isolated existence within royalty’s privileged cocoon.

“Nothing is private when you are the daughter of England’s sovereign,” writes Heather B. Moore in her biographical novel about Princess Louise, succinctly stating her heroine’s predicament and illustrating the difficult path she navigates as she gingerly moves out of Queen Victoria’s shadow and into a role that offers greater fulfillment.

Sadly, Louise’s childhood is dominated by her father Prince Albert’s early death and her mother’s stifling control and refusal to emerge from mourning. Each of Victoria’s unmarried daughters, in turn, is expected to serve as her personal secretary, a role she thinks Louise is too excitable and strong-willed to handle. Louise’s few friendships are supervised, and her associations with outsiders strictly limited.

A good part of the novel involves the husband hunt, a challenging task since there are few good options. Moore nimbly sketches in the political background that overshadows Louise’s choices (many potential fiancés are objectionable to either the Danes or the Prussians, whose families Louise’s older siblings married into, and who are in a territorial dispute). Also, the Queen doesn’t want her to reside abroad. Louise finds the whole process embarrassing, and it’s clear why that is. How could anyone possibly be themselves while dating – to use a modern term – under the view of multiple chaperones?

The standout scenes are those where Louise asserts her independence: perfecting her sculpting abilities to the point where she wears down her mother’s objections to further training; stepping from her carriage into the halls of the art school; daring to visit physician Elizabeth Garrett at her home and pose questions about women in medicine. Queen Victoria’s sense of royal dignity is such that, when Louise does get engaged, she demands that her future husband call her “Princess Louise” all the time – even in private! Louise is her own woman, though, and knows that’s not the type of marriage she wants.

Following Louise from ages 12 through 23, In the Shadow of a Queen uses excerpts from historical letters to start each chapter, and the author’s prose approximates the same tone and characterizations. Moore has done careful research, and her endnotes – which are so detailed that the actual novel ends at the 90% mark on my Kindle – emphasize her dedication to the source material. Readers hoping to find secret love affairs or other juicy rumors brought to life should look elsewhere. Instead, they’ll find a well-rendered, convincing portrait of a talented young woman’s efforts to balance her royal role with her need for independence.

The novel is published by Shadow Mountain Publishing today, October 4th, and my review is part of the blog tour with Austenprose PR (I read it from a NetGalley copy).

“Nothing is private when you are the daughter of England’s sovereign,” writes Heather B. Moore in her biographical novel about Princess Louise, succinctly stating her heroine’s predicament and illustrating the difficult path she navigates as she gingerly moves out of Queen Victoria’s shadow and into a role that offers greater fulfillment.

Sadly, Louise’s childhood is dominated by her father Prince Albert’s early death and her mother’s stifling control and refusal to emerge from mourning. Each of Victoria’s unmarried daughters, in turn, is expected to serve as her personal secretary, a role she thinks Louise is too excitable and strong-willed to handle. Louise’s few friendships are supervised, and her associations with outsiders strictly limited.

A good part of the novel involves the husband hunt, a challenging task since there are few good options. Moore nimbly sketches in the political background that overshadows Louise’s choices (many potential fiancés are objectionable to either the Danes or the Prussians, whose families Louise’s older siblings married into, and who are in a territorial dispute). Also, the Queen doesn’t want her to reside abroad. Louise finds the whole process embarrassing, and it’s clear why that is. How could anyone possibly be themselves while dating – to use a modern term – under the view of multiple chaperones?

The standout scenes are those where Louise asserts her independence: perfecting her sculpting abilities to the point where she wears down her mother’s objections to further training; stepping from her carriage into the halls of the art school; daring to visit physician Elizabeth Garrett at her home and pose questions about women in medicine. Queen Victoria’s sense of royal dignity is such that, when Louise does get engaged, she demands that her future husband call her “Princess Louise” all the time – even in private! Louise is her own woman, though, and knows that’s not the type of marriage she wants.

|

| author Heather B. Moore |

The novel is published by Shadow Mountain Publishing today, October 4th, and my review is part of the blog tour with Austenprose PR (I read it from a NetGalley copy).

AMAZON | BARNES & NOBLE | BOOK DEPOSITORY | BOOKSHOP | GOODREADS

AUTHOR BIO

Heather B. Moore is

a USA Today best-selling and award-winning author of more than

seventy publications, including The Paper Daughters of Chinatown.

She has lived on both the East and West Coasts of the United States, as well as

Hawaii, and attended school abroad at the Cairo American Collage in Egypt and

the Anglican School of Jerusalem in Israel. She loves to learn about history

and is passionate about historical research.

Monday, August 29, 2022

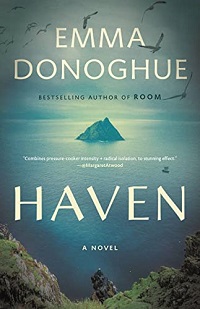

Emma Donoghue's Haven, set in early 7th-century Ireland, explores the demands of faith and obedience

Skellig Michael, a steep, rocky island off the southwestern Irish coast, is the setting for this atmospheric work, an imagined story about its early human inhabitants.

In the seventh century, Artt, a scholar-priest guided by a dream, asks two monks to join him on a pilgrimage to an empty isle “less tainted by the world’s breath.” Excited at achieving a greater life purpose, the elderly Cormac, a talented storyteller and mason, agrees to go, as does Trian, a lanky, adventurous younger man.

From the days-long boat journey through their mission to establish an island settlement and worship God appropriately, their work is arduous. Donoghue’s (The Pull of the Stars, 2020) prose glimmers with images of the pristine natural world, including many varieties of sea birds, but as Artt’s sanctimonious piety increasingly challenges common sense, Cormac and Trian wonder if their vows of obedience will doom them.

As always, Donoghue extracts realistic emotions from characters interacting within close quarters and delicately explores the demands of faith. This evocative historical novel also works as a cautionary tale about the dangers of religious control.

I wrote this review for the June 1st issue of Booklist. Haven was published by Little, Brown (US) last Tuesday, August 23rd. Isn't the cover art gorgeous? I'm a fan of Emma Donoghue's work, and my favorites are Frog Music and The Wonder, the latter of which is soon to be available as a Netflix film starring Florence Pugh.

For additional perspectives (which are also positive recommendations), please check out Kristen McDermott's review of Haven for the Historical Novels Review as well as Ron Charles's review for the Washington Post. I always enjoy seeing other reviewers' takes on novels I've read myself. Charles's description of Haven as "Room with a view" is an inspired, smart observation that's remarkably accurate!

Emma Donoghue was also interviewed by Margaret Skea for the Historical Novels Review's August issue, and you can read that piece here.

In the seventh century, Artt, a scholar-priest guided by a dream, asks two monks to join him on a pilgrimage to an empty isle “less tainted by the world’s breath.” Excited at achieving a greater life purpose, the elderly Cormac, a talented storyteller and mason, agrees to go, as does Trian, a lanky, adventurous younger man.

From the days-long boat journey through their mission to establish an island settlement and worship God appropriately, their work is arduous. Donoghue’s (The Pull of the Stars, 2020) prose glimmers with images of the pristine natural world, including many varieties of sea birds, but as Artt’s sanctimonious piety increasingly challenges common sense, Cormac and Trian wonder if their vows of obedience will doom them.

As always, Donoghue extracts realistic emotions from characters interacting within close quarters and delicately explores the demands of faith. This evocative historical novel also works as a cautionary tale about the dangers of religious control.

I wrote this review for the June 1st issue of Booklist. Haven was published by Little, Brown (US) last Tuesday, August 23rd. Isn't the cover art gorgeous? I'm a fan of Emma Donoghue's work, and my favorites are Frog Music and The Wonder, the latter of which is soon to be available as a Netflix film starring Florence Pugh.

For additional perspectives (which are also positive recommendations), please check out Kristen McDermott's review of Haven for the Historical Novels Review as well as Ron Charles's review for the Washington Post. I always enjoy seeing other reviewers' takes on novels I've read myself. Charles's description of Haven as "Room with a view" is an inspired, smart observation that's remarkably accurate!

Emma Donoghue was also interviewed by Margaret Skea for the Historical Novels Review's August issue, and you can read that piece here.

Monday, November 08, 2021

Review of Paulette Kennedy's Parting the Veil, a Victorian romantic suspense debut

Paulette Kennedy’s debut, Parting the Veil, is a veritable Gothic feast. Romantic suspense is a genre the author clearly loves, and the novel’s stuffed full of its hallmarks and tropes: a single woman, a mysterious inheritance, a crumbling mansion reputed to be haunted, its broodingly handsome owner, a shocking Tarot card reading… and that’s just to start.

The fun is in recognizing which of these elements will play out as expected, and which will be given an unexpected twist.

In 1899, Eliza Sullivan and her younger, mixed-race half-sister Lydia, natives of New Orleans, arrive in the Hampshire village of Chesterbridge to take up residence at Sherbourne House, which had been left to Eliza by a great-aunt she barely knew. The terms of Tante Theo’s bequest, though, disconcert the independent-minded heiress. Eliza learns that to take possession of her fortune, she must get married within three months.

Malcolm, Viscount Havenwood, is the sole surviving member of his family after a fire three years earlier damaged his home’s south wing. An immediate physical attraction springs up between Eliza and Malcolm. She throws caution to the wind and – against the practical Lydia’s advice – weds him.

But married life perplexes Eliza. While ardent in the bedroom at night, Malcolm is cold and proper, even condescending, during the day. His behavior will have readers wondering whether Malcolm deserves a happily-ever-after with our heroine.

A profusion of mysteries drives the story along. What (or who) causes the rhythmic tapping Eliza hears at night? What happened to Malcolm’s Scottish mother, who was rumored to be mad? Why does he behave so weirdly? Why is Eliza haunted by painful childhood memories?

The atmosphere is a piquant blend of Southern Gothic meets Jane Eyre. As Americans, Eliza and Lydia’s entrance into Hampshire society meets with curiosity; contrary to stereotype, though, they aren't treated like unwelcome outsiders. They form friendships with local women, including newlywed Sarah Nelson, whose candor is a breath of fresh air. There are hints of same-sex relationships in some women’s pasts, which add layers of intrigue. (One minor complaint: the pet name “darling” is overused.)

For readers on the fence about romantic suspense, the ambience may be overwhelming. But for those who adore it, settle into this compulsive read and soak it all in.

The fun is in recognizing which of these elements will play out as expected, and which will be given an unexpected twist.

In 1899, Eliza Sullivan and her younger, mixed-race half-sister Lydia, natives of New Orleans, arrive in the Hampshire village of Chesterbridge to take up residence at Sherbourne House, which had been left to Eliza by a great-aunt she barely knew. The terms of Tante Theo’s bequest, though, disconcert the independent-minded heiress. Eliza learns that to take possession of her fortune, she must get married within three months.

Malcolm, Viscount Havenwood, is the sole surviving member of his family after a fire three years earlier damaged his home’s south wing. An immediate physical attraction springs up between Eliza and Malcolm. She throws caution to the wind and – against the practical Lydia’s advice – weds him.

But married life perplexes Eliza. While ardent in the bedroom at night, Malcolm is cold and proper, even condescending, during the day. His behavior will have readers wondering whether Malcolm deserves a happily-ever-after with our heroine.

A profusion of mysteries drives the story along. What (or who) causes the rhythmic tapping Eliza hears at night? What happened to Malcolm’s Scottish mother, who was rumored to be mad? Why does he behave so weirdly? Why is Eliza haunted by painful childhood memories?

|

| author Paulette Kennedy |

The atmosphere is a piquant blend of Southern Gothic meets Jane Eyre. As Americans, Eliza and Lydia’s entrance into Hampshire society meets with curiosity; contrary to stereotype, though, they aren't treated like unwelcome outsiders. They form friendships with local women, including newlywed Sarah Nelson, whose candor is a breath of fresh air. There are hints of same-sex relationships in some women’s pasts, which add layers of intrigue. (One minor complaint: the pet name “darling” is overused.)

For readers on the fence about romantic suspense, the ambience may be overwhelming. But for those who adore it, settle into this compulsive read and soak it all in.

Parting the Veil is published by Lake Union this month; I read it from a NetGalley copy as part of the blog tour for Historical Fiction Virtual Book Tours.

Sunday, July 18, 2021

The Lengthening Shadow by Liz Harris, a saga set in England and Germany between the world wars

The title of this fast-paced and memorable saga, spanning from 1914 through 1934 in England and Germany, reflects the historical atmosphere: the darkness spreading across the land as the Nazis rise in power and influence, and its chilling effect on the people living beneath it.

Each volume in the Linford series focuses on different characters. In this third entry, the protagonists are Dorothy Linford, eldest daughter of Joseph, chairman of a prominent London-based building company; and her troubled younger cousin, Louisa. Although some material overlaps with the previous two books, they can all be read independently, and readers familiar with the saga will appreciate how Harris has avoided spoilers for The Dark Horizon (book one) and The Flame Within (book two) – this is very skillfully done!

Serving as a nurse with the Voluntary Aid Detachment during WWI, Dorothy meets and falls in love with one of her hospital patients, Franz Hartmann, a German internee. Disowned by her parents after their marriage, Dorothy moves with Franz to Germany, where they raise two children. Although she misses England dreadfully, she loves the friendliness and religious amity in their small town, Rundheim.

Through the experiences of the Hartmanns and their neighbors, the novel shows the subtle and, later, overt pressures that ordinary German citizens felt to support Hitler, even against their better judgment. One scene set in 1933, where the view from a mountain hike sweeps from the beauteous natural backdrop to the swastika flags flying from windows below, evokes an unsettling contrast.

As her worry and fear grow, Dorothy has painful decisions to make. Back in England, Louisa, a surly teenager, must reassess her priorities after a major wrongdoing. The characters realistically grow and change, and readers will turn the pages eagerly, hoping for optimistic endings for them all.

The Lengthening Shadow was published by Heywood Press in 2021; I reviewed it for May's Historical Novels Review. This is the third and last book in the Linford series. The author's next historical novel, The Darjeeling Inheritance, out in October, is set in India in 1930. I look forward to reading it.

Each volume in the Linford series focuses on different characters. In this third entry, the protagonists are Dorothy Linford, eldest daughter of Joseph, chairman of a prominent London-based building company; and her troubled younger cousin, Louisa. Although some material overlaps with the previous two books, they can all be read independently, and readers familiar with the saga will appreciate how Harris has avoided spoilers for The Dark Horizon (book one) and The Flame Within (book two) – this is very skillfully done!

Serving as a nurse with the Voluntary Aid Detachment during WWI, Dorothy meets and falls in love with one of her hospital patients, Franz Hartmann, a German internee. Disowned by her parents after their marriage, Dorothy moves with Franz to Germany, where they raise two children. Although she misses England dreadfully, she loves the friendliness and religious amity in their small town, Rundheim.

Through the experiences of the Hartmanns and their neighbors, the novel shows the subtle and, later, overt pressures that ordinary German citizens felt to support Hitler, even against their better judgment. One scene set in 1933, where the view from a mountain hike sweeps from the beauteous natural backdrop to the swastika flags flying from windows below, evokes an unsettling contrast.

As her worry and fear grow, Dorothy has painful decisions to make. Back in England, Louisa, a surly teenager, must reassess her priorities after a major wrongdoing. The characters realistically grow and change, and readers will turn the pages eagerly, hoping for optimistic endings for them all.

The Lengthening Shadow was published by Heywood Press in 2021; I reviewed it for May's Historical Novels Review. This is the third and last book in the Linford series. The author's next historical novel, The Darjeeling Inheritance, out in October, is set in India in 1930. I look forward to reading it.

Tuesday, May 04, 2021

Hour of the Witch by Chris Bohjalian, a thrilling novel of 17th-century New England

How far will a woman go to escape an abusive husband? In Puritan Boston in 1662, divorces are rarely granted, but Mary Deerfield, a beautiful 24-year-old goodwife, sees no alternative. Barren after five years of marriage to Thomas, a prosperous miller in his mid-forties, Mary conceals bruises beneath her coif and brushes off concerns from her adult stepdaughter.

Thomas has a pattern of returning “drink-drunk” from the tavern, taking his anger out on Mary, and apologizing the next morning. Their indentured servant, who admires Thomas, never sees any violence, only a husband properly correcting his wife. Then comes the evening when Thomas attacks Mary’s left hand with a fork.

Mary has allies, most notably her caring, wealthy parents. But in a culture that views women as subservient helpmeets, and with no witnesses to Thomas’s cruelty, Mary’s petition has slim chances. She must also tread carefully: the Hartford witch-hunts weigh on people’s minds, some of her behavior appears suspicious, and Satan’s temptations lurk everywhere.

Themes of women’s agency in a patriarchal society are common in historical novels, but this fast-moving, darkly suspenseful novel stands out with Bohjalian’s extraordinary world-building skills. From speech patterns to the detailed re-creation of colonial households to the religious mindset, the historical setting is very credible.

The rich have finer options—Mary’s mother wears vivid colors, for instance—but her father struggles to get across that the three-pronged forks he imports from abroad are just utensils, not the “Devil’s tines.” Mary isn’t an outspoken iconoclast but a product of her era, and readers will worry for her—for many reasons, which become clear as the story progresses.

The quotes opening each chapter, taken from court proceedings occurring later on, diminish some of the novel’s surprises. Nonetheless, the plot moves with increasing urgency that will have readers racing toward the ending.

Hour of the Witch is published today by Doubleday; I reviewed it from NetGalley for the Historical Novels Review. If this doesn't convince you to read it, also check out Diana Gabaldon's recent review for the Washington Post.

Thomas has a pattern of returning “drink-drunk” from the tavern, taking his anger out on Mary, and apologizing the next morning. Their indentured servant, who admires Thomas, never sees any violence, only a husband properly correcting his wife. Then comes the evening when Thomas attacks Mary’s left hand with a fork.

Mary has allies, most notably her caring, wealthy parents. But in a culture that views women as subservient helpmeets, and with no witnesses to Thomas’s cruelty, Mary’s petition has slim chances. She must also tread carefully: the Hartford witch-hunts weigh on people’s minds, some of her behavior appears suspicious, and Satan’s temptations lurk everywhere.

Themes of women’s agency in a patriarchal society are common in historical novels, but this fast-moving, darkly suspenseful novel stands out with Bohjalian’s extraordinary world-building skills. From speech patterns to the detailed re-creation of colonial households to the religious mindset, the historical setting is very credible.

The rich have finer options—Mary’s mother wears vivid colors, for instance—but her father struggles to get across that the three-pronged forks he imports from abroad are just utensils, not the “Devil’s tines.” Mary isn’t an outspoken iconoclast but a product of her era, and readers will worry for her—for many reasons, which become clear as the story progresses.

The quotes opening each chapter, taken from court proceedings occurring later on, diminish some of the novel’s surprises. Nonetheless, the plot moves with increasing urgency that will have readers racing toward the ending.

Hour of the Witch is published today by Doubleday; I reviewed it from NetGalley for the Historical Novels Review. If this doesn't convince you to read it, also check out Diana Gabaldon's recent review for the Washington Post.

Sunday, April 18, 2021

Women in the margins: Pip Williams' The Dictionary of Lost Words

Some historical novels forever change the way you think about their subjects. Pip Williams’ debut novel is one of these.

Moving from the late Victorian period through the suffrage movement, World War I, and after, The Dictionary of Lost Words examines with a questioning eye the painstaking process involved in producing the Oxford English Dictionary. Scholars are so used to regarding this masterwork as an authoritative reference for meanings and etymologies that it’s easy to forget that, as a product of human labor, its contents reflected the fallibility and biases of its compilers and its era.

The narrator, Esme Nicoll, is the daughter of one of the OED’s lexicographers. Her mother had died in childbirth, so Esme’s father, Harry, is obliged to bring her with him to his office in Oxford. As Harry and his male colleagues collect words, definitions, and quotes on slips of paper, young Esme spends her days concealed under their worktables in the Scriptorium (a building resembling a garden shed) near the house of the dictionary’s principal editor, James Murray.

When one slip floats down to her on the floor, forgotten, she claims it, reads the word – “bondmaid” – and learns what it means. (This word really did slip through the cracks.) Thus begins Esme’s private collection of words omitted from the dictionary. She becomes attuned to the reasons that words are left out: for example, if they’re quoted only in books written by women (and considered of lower importance), or if they have the potential to offend (such as those referring to female body parts). Slang only spoken aloud doesn’t get included, either.

As she grows up, Esme takes it upon herself to gather as many of these “lost words” as possible, using the local community of women as her informants. These include the Murrays’ illiterate maid, Lizzie, who loves her like a younger sister, and Mabel O’Shaughnessy, a poor, shabbily dressed woman with a raunchy vocabulary who has a stall at the Covered Market. These women, terrific characters both, have their own hard-earned wisdom. Who’s to say that their words aren’t worth recording?

Esme’s journey is not just an intellectual exercise but also an emotional one, related with deep empathy by the author. She soaks up life along with the words describing it, feeling their joys and many sorrows. Meanwhile, work on the OED continues, and Esme yearns to be a full contributor. Pip Williams also manages to create an overtly feminine-centered narrative without stereotyping its men. Harry Nicoll obviously loves his daughter, encourages her curiosity, and supports her in times of strife. Sometimes the story is almost too sad to bear, but there’s beauty within the melancholy, and hope shines through at the end.

Esme is a fictional character, but her presence in this historically based story isn’t too much of an imaginative stretch. Women did play roles in the OED’s creation, although they didn’t receive proper acknowledgment. In The Dictionary of Lost Words, Pip Williams lifts them out of the margins of the OED and gives them, and their words, the recognition they deserve.

If you’ve read this far, and are curious to learn more, please jump over to the author’s website to read her blog post on the real history, Reflecting on the work of women in compiling the Oxford English Dictionary.

Moving from the late Victorian period through the suffrage movement, World War I, and after, The Dictionary of Lost Words examines with a questioning eye the painstaking process involved in producing the Oxford English Dictionary. Scholars are so used to regarding this masterwork as an authoritative reference for meanings and etymologies that it’s easy to forget that, as a product of human labor, its contents reflected the fallibility and biases of its compilers and its era.

The narrator, Esme Nicoll, is the daughter of one of the OED’s lexicographers. Her mother had died in childbirth, so Esme’s father, Harry, is obliged to bring her with him to his office in Oxford. As Harry and his male colleagues collect words, definitions, and quotes on slips of paper, young Esme spends her days concealed under their worktables in the Scriptorium (a building resembling a garden shed) near the house of the dictionary’s principal editor, James Murray.

When one slip floats down to her on the floor, forgotten, she claims it, reads the word – “bondmaid” – and learns what it means. (This word really did slip through the cracks.) Thus begins Esme’s private collection of words omitted from the dictionary. She becomes attuned to the reasons that words are left out: for example, if they’re quoted only in books written by women (and considered of lower importance), or if they have the potential to offend (such as those referring to female body parts). Slang only spoken aloud doesn’t get included, either.

As she grows up, Esme takes it upon herself to gather as many of these “lost words” as possible, using the local community of women as her informants. These include the Murrays’ illiterate maid, Lizzie, who loves her like a younger sister, and Mabel O’Shaughnessy, a poor, shabbily dressed woman with a raunchy vocabulary who has a stall at the Covered Market. These women, terrific characters both, have their own hard-earned wisdom. Who’s to say that their words aren’t worth recording?

Esme’s journey is not just an intellectual exercise but also an emotional one, related with deep empathy by the author. She soaks up life along with the words describing it, feeling their joys and many sorrows. Meanwhile, work on the OED continues, and Esme yearns to be a full contributor. Pip Williams also manages to create an overtly feminine-centered narrative without stereotyping its men. Harry Nicoll obviously loves his daughter, encourages her curiosity, and supports her in times of strife. Sometimes the story is almost too sad to bear, but there’s beauty within the melancholy, and hope shines through at the end.

Esme is a fictional character, but her presence in this historically based story isn’t too much of an imaginative stretch. Women did play roles in the OED’s creation, although they didn’t receive proper acknowledgment. In The Dictionary of Lost Words, Pip Williams lifts them out of the margins of the OED and gives them, and their words, the recognition they deserve.

If you’ve read this far, and are curious to learn more, please jump over to the author’s website to read her blog post on the real history, Reflecting on the work of women in compiling the Oxford English Dictionary.

The Dictionary of Lost Words is published by Ballantine this month in the US. In Australia, where it became a bestseller, the publisher is Affirm Press. I read it from a NetGalley copy.

Thursday, March 04, 2021

W. S. Winslow visits small-town Maine across the 20th century in The Northern Reach

There’s a large genealogical chart at the beginning of W. S. Winslow’s debut novel, a collection of integrated stories set in and around the small coastal town of Wellbridge, Maine, across the twentieth century and beyond. The timeline for this saga is as original as the many individuals populating it. The tales move forward and back in time, sometimes zipping along the chart on the diagonal as they center on separate families – the Lawsons, Moody, Baineses, and Martins – linked by blood, marriage, and illicit relationships.

The Northern Reach recounts how the unforgiving environment molds its characters, who have mixed or antagonistic reactions to their hometown. The austerity of the locale suffuses many lives, and happiness can be as fleeting as the summer temperatures. Perhaps it’s not surprising that the hero of one story ends up as the villain in a tale set a generation later.

The most sympathetic characters are those who consider themselves outsiders – those who escape from Wellbridge or want to. Among them are Liliane, a Frenchwoman who in 1958 meets fisherman Mason Baines, a handsome sailor in the merchant marines, marries him, and raises two children. Her foreign ways are denigrated by her narrow-minded mother-in-law, Edith. Edith appears as an elderly woman in the opening story, her mind fading as she stares out to sea following her husband’s and favorite son’s deaths in a boating accident.

Winslow incorporates dark humor in the tale of Victoria Moody, who returns to Wellbridge after ten years’ absence to attend her father’s funeral. Relieved to have left her fiancé back in Portland, away from the “horror show” of her embarrassing family, she finds it impossible to leave the past behind. Another insightful story shows a woman’s ghost coming face to face with her children’s true feelings, learning details they never spoke in her presence during her lifetime.

In the earliest accounts, especially, the bleakness can be overwhelming, but the descriptions create memorable images nonetheless: “Above the reach low clouds sleepwalk across the February sky. Today they are fibrous, striated, like flesh being slowly torn from bone.” Other observations about troubled lives pique the imagination with their realness. Admirers of character-centered historical fiction will find much to like in these introspective stories.

The Northern Reach recounts how the unforgiving environment molds its characters, who have mixed or antagonistic reactions to their hometown. The austerity of the locale suffuses many lives, and happiness can be as fleeting as the summer temperatures. Perhaps it’s not surprising that the hero of one story ends up as the villain in a tale set a generation later.

The most sympathetic characters are those who consider themselves outsiders – those who escape from Wellbridge or want to. Among them are Liliane, a Frenchwoman who in 1958 meets fisherman Mason Baines, a handsome sailor in the merchant marines, marries him, and raises two children. Her foreign ways are denigrated by her narrow-minded mother-in-law, Edith. Edith appears as an elderly woman in the opening story, her mind fading as she stares out to sea following her husband’s and favorite son’s deaths in a boating accident.

Winslow incorporates dark humor in the tale of Victoria Moody, who returns to Wellbridge after ten years’ absence to attend her father’s funeral. Relieved to have left her fiancé back in Portland, away from the “horror show” of her embarrassing family, she finds it impossible to leave the past behind. Another insightful story shows a woman’s ghost coming face to face with her children’s true feelings, learning details they never spoke in her presence during her lifetime.

In the earliest accounts, especially, the bleakness can be overwhelming, but the descriptions create memorable images nonetheless: “Above the reach low clouds sleepwalk across the February sky. Today they are fibrous, striated, like flesh being slowly torn from bone.” Other observations about troubled lives pique the imagination with their realness. Admirers of character-centered historical fiction will find much to like in these introspective stories.

The Northern Reach is published by Flatiron this month; thanks to the publisher for the e-copy.

Wednesday, February 24, 2021

Zorrie by Laird Hunt observes a woman's 20th-century life in the rural Midwest

Deliberately echoing the form of Gustave Flaubert’s novella, “A Simple Heart,” Hunt celebrates the majesty and depth in a life that may superficially seem undistinguished. Zorrie Underwood is a farmer in central Indiana, and as she and readers survey her 70-or-so years, her joys and sorrows are deeply observed and felt.

Raised by a cranky aunt, Zorrie is left homeless at 21, in 1930, and travels though the countryside doing odd jobs for food. Following a stint painting clock faces at the Radium Dial Company in Ottawa, Illinois, she settles in her home state and marries a kindly couple’s farmer son, enduring setbacks and grief while adhering to daily routines.

With compassion and realism, Hunt recounts Zorrie’s story straightforwardly, with setting-appropriate dialogue and an eye for sensory details: the glint of fireflies, the clay soil’s rich scent, the “mineral-sweet taste of warm blackberries picked off the vines.” Zorrie’s relationship with her neighbor Noah Summers, the eccentric protagonist of Hunt’s Indiana, Indiana (2003), is presented with expressive subtlety. A beautifully written ode to the rural Midwest.

Zorrie was published by Bloomsbury this month, and I'd reviewed it from an Edelweiss e-copy for the Nov. 1st issue of Booklist. I was impressed by how well Hunt encapsulated a full life within a novella of fewer than 200 pages. Living in the rural Midwest myself (Illinois rather than Indiana), I recognized the landscapes of the story. You can find more background on the Radium Dial Company and the young female dial-painters employed there in Kate Moore's bestselling The Radium Girls.

Sunday, December 20, 2020

Snow by John Banville, a chilling historical mystery set in 1950s Ireland

Snow: cold, soft, brilliantly blinding. It muffles sound and casts a thick shroud over whatever lies beneath. The symbolism is apropos in Banville’s newest crime novel, the first to be written under his own name rather than the pseudonym (Benjamin Black) he’d established for genre-fiction purposes.

Snow takes place in County Wexford, Ireland, a time when the Catholic Church reigned supreme and buried its adversaries. One frigid day in 1957, Detective Inspector St. John (pronounced “Sinjun”) Strafford arrives at Ballyglass House to investigate a murder. The body of Father Tom Lawless, longtime friend of the Osborne family, lies on the floor of the ornate library, throat cut and private parts removed. A parish priest’s killing is bizarre enough on its own, and almost no one seems upset about it. Strafford shares the privileged Protestant background of the Osbornes but finds, to his annoyance, that this doesn’t gain him any ground in his sleuthing.

The story appears to follow a standard country-house mystery plot, with a closed-in setting and characters fitting familiar types: a refined patriarch, his attractive younger wife, their rebellious adult children. Banville peels away at these tropes as the personalities behind the theatrical parts make themselves known. Strafford is himself an intriguing figure, both in his career – most policemen in the Garda are Catholic – and in his reactions to the women he meets.

That said, he’s surprisingly slow on the uptake in pinpointing motive. An interlude late in the story, seen from Father Tom’s viewpoint, makes things clear for anyone who hasn’t yet figured it out. Banville has a consummate hand with establishing atmosphere, though, in sentences of chillingly ethereal beauty: “Surely such a violent act should leave something behind, a trace, a tremor in the air, like the hum that lingers when a bell stops tolling?”

Snow takes place in County Wexford, Ireland, a time when the Catholic Church reigned supreme and buried its adversaries. One frigid day in 1957, Detective Inspector St. John (pronounced “Sinjun”) Strafford arrives at Ballyglass House to investigate a murder. The body of Father Tom Lawless, longtime friend of the Osborne family, lies on the floor of the ornate library, throat cut and private parts removed. A parish priest’s killing is bizarre enough on its own, and almost no one seems upset about it. Strafford shares the privileged Protestant background of the Osbornes but finds, to his annoyance, that this doesn’t gain him any ground in his sleuthing.

The story appears to follow a standard country-house mystery plot, with a closed-in setting and characters fitting familiar types: a refined patriarch, his attractive younger wife, their rebellious adult children. Banville peels away at these tropes as the personalities behind the theatrical parts make themselves known. Strafford is himself an intriguing figure, both in his career – most policemen in the Garda are Catholic – and in his reactions to the women he meets.

That said, he’s surprisingly slow on the uptake in pinpointing motive. An interlude late in the story, seen from Father Tom’s viewpoint, makes things clear for anyone who hasn’t yet figured it out. Banville has a consummate hand with establishing atmosphere, though, in sentences of chillingly ethereal beauty: “Surely such a violent act should leave something behind, a trace, a tremor in the air, like the hum that lingers when a bell stops tolling?”

Snow was published by Hanover Square Press in October; in the UK, Faber and Faber is the publisher. I reviewed it for the Historical Novels Review from a NetGalley copy. This novel seemed apropos for this time of year in the US Midwest. This is my first time reading one of John Banville's (that is, Benjamin Black's) crime novels; if you've read others you'd recommend, please comment.

Saturday, November 28, 2020

The Four Winds by Kristin Hannah, her forthcoming epic about women's strength during the Dust Bowl

With this emotionally charged epic of Dust Bowl-era Texas and its dramatic aftermath, the prolific Hannah has added another outstanding novel to her popular repertoire.

In 1921, Elsa Wolcott is a tall, bookish woman of 25 whose soul is stifled by her superficial parents. By 1934, after marrying Rafe Martinelli, a young Italian Catholic who was the first man to show her affection, Elsa is a mother of two who has found a home on her beloved in-laws’ farm. Severe drought and terrible dust storms affect everyone in this proud family, and they are all forced to make tough choices.

This wide-ranging saga ticks all the boxes for deeply satisfying historical fiction. Elsa is an achingly real character whose sense of self-worth slowly emerges through trying circumstances, and her shifting relationship with her rebellious daughter, Loreda, is particularly moving. Hannah brings the impact of the environmental devastation on the Great Plains down to a personal level with ample period-appropriate details and reactions, showing how people’s love for their land made them reluctant to leave.

The storytelling is propulsive, and the contemporary relevance of the novel’s themes—for example, how outsiders are unfairly blamed for economic inequities—provides additional depth in this rich, rewarding read about family ties, perseverance, and women’s friendships and fortitude.

The Four Winds will be published by St. Martin's Press in February 2021. I'd reviewed it from an Edelweiss e-copy for Booklist's 10/15/20 issue. Hannah's earlier historical novel, The Nightingale, was the historical fiction category winner in the Goodreads Choice awards for 2015 (I haven't read it yet, so no spoilers, please!). Will you be reading this one, and which among her works is your favorite so far? Happy to hear your recommendations.

Monday, October 19, 2020

We All Fall Down: Stories of Plague and Resilience, nine historically rich tales

I wasn’t always a fan of historical short stories. The format seemed too concise to support the world-building and character depth necessary for the genre. But the more I read, the more I grew to appreciate them. Short stories are powerfully concentrated in terms of character, plot, and historical detail. When done right, the length suits the material perfectly.

Several weeks ago, I watched a Zoom panel, “Stories of Plague in the time of Covid,” sponsored by the Historical Novel Society NYC Chapter, over my lunch hour. A collection of international authors who contributed to the We All Fall Down anthology spoke about their stories and took questions. It was one of the best online panels I’ve seen, and now that I’ve read the book, I’m tempted to watch it again.

The book was conceptualized long before the current pandemic, and it’s eerie how well some situations in the nine tales reflect our time. All are set during periods of the Black Death between the 14th and 17th centuries: stories of sorrow, grief, family, love, art, beauty, and the strength to survive after immense loss.

Kristin Gleeson’s “The Blood of the Gaels,” set in Ireland in 1348, follows a young novice as she travels home to her family after getting word of her father’s illness. This unpredictable story has hints of mystery as it showcases the religion, folk beliefs, and laws of the time.

“The Heretic” by Lisa J. Yarde introduced me to a less familiar period, 14th-century Moorish Spain, and to the historical figure of Ibn al-Khatib, personal secretary to the sultan, who observes how the plague is spreading and develops controversial views about how to lessen its severity. I highlighted multiple passages that felt historically relevant and uncannily familiar to today.

Lastly, “778” by Melodie Winawer, a tale of regret and resilience, shows how the rapidly shifting political climate in 17th-century Mystras, Greece, affects everyone in a Turkish man’s household. The arrival of plague adds to the heightened tensions.

A wide-ranging, rich collection of human experiences, all contained in a collection of fewer than 200 pages. This was a personal purchase. Hope this post encourages others to check it out for themselves. You can watch the YouTube recording of the panel below.

Several weeks ago, I watched a Zoom panel, “Stories of Plague in the time of Covid,” sponsored by the Historical Novel Society NYC Chapter, over my lunch hour. A collection of international authors who contributed to the We All Fall Down anthology spoke about their stories and took questions. It was one of the best online panels I’ve seen, and now that I’ve read the book, I’m tempted to watch it again.

The book was conceptualized long before the current pandemic, and it’s eerie how well some situations in the nine tales reflect our time. All are set during periods of the Black Death between the 14th and 17th centuries: stories of sorrow, grief, family, love, art, beauty, and the strength to survive after immense loss.

Kristin Gleeson’s “The Blood of the Gaels,” set in Ireland in 1348, follows a young novice as she travels home to her family after getting word of her father’s illness. This unpredictable story has hints of mystery as it showcases the religion, folk beliefs, and laws of the time.

“The Heretic” by Lisa J. Yarde introduced me to a less familiar period, 14th-century Moorish Spain, and to the historical figure of Ibn al-Khatib, personal secretary to the sultan, who observes how the plague is spreading and develops controversial views about how to lessen its severity. I highlighted multiple passages that felt historically relevant and uncannily familiar to today.

Following a girl as she hawks elixirs with her motley group of faith-healers and fraudsters on their travels through 14th-century Siena, Laura Morelli’s “Little Bird” draws readers into the world of the Lorenzetti painters as the “Great Mortality” lands in the city – perhaps, as was thought, as punishment for its residents’ sins. This was one of my favorites, for its re-creation of the tools of the artists’ workshop and the glories of medieval Siena: “The cathedral is a chamber of echoing footsteps and pigeon wings, lit by dozens of gilded altarpieces shimmering in the candlelight.”

As a reader interested in fiction about little-known royal figures, I appreciated J. K. Knauss’s illustration of the life of Leonor de Guzmán, mistress of Alfonso XI of Castile, and the challenges she faces after he dies of plague in 14th-century Seville.

With the poignantly meditative “On All Our Houses,” set in Gargagnago, Italy, in 1362, David Blixt revisits his character Pietro Alighieri (Dante’s son) later in life. Aged 64, Pietro reflects on his existence and the fearsome inevitability of death as his eldest daughter Betha lies dying of plague.

Moving ahead to Venice (Venezia) in 1576, Jean Gill’s “A Certain Shade of Red,” replete with historical detail and symbolism, is narrated by Death himself as he observes the famous painter, Tician (Titian), dying of pestilence, and at earlier moments in his life. Then, as now, political leaders make choices about public health vs. the economy; these passages hit home.

“The Repentant Thief” by Deborah Swift stars an Irish immigrant boy in 1645 Edinburgh who steals a coin and locket from a tenement he’s broken into and then, as plague spreads, worries he’s brought God’s wrath down on his family. Historical atmosphere, well-wrought characters, realistic dialogue, pertinent themes, and a great ending: they’re all here.

Demonstrating the state of health care at the time, Katherine Pym’s “Arrows that Fly in the Dark” takes the perspective of time-traveling youths who inhabit the bodies of a physician’s apprentices in 1665 London. They find their master’s techniques for protecting against plague distasteful and sometimes ridiculous.

As a reader interested in fiction about little-known royal figures, I appreciated J. K. Knauss’s illustration of the life of Leonor de Guzmán, mistress of Alfonso XI of Castile, and the challenges she faces after he dies of plague in 14th-century Seville.

With the poignantly meditative “On All Our Houses,” set in Gargagnago, Italy, in 1362, David Blixt revisits his character Pietro Alighieri (Dante’s son) later in life. Aged 64, Pietro reflects on his existence and the fearsome inevitability of death as his eldest daughter Betha lies dying of plague.

Moving ahead to Venice (Venezia) in 1576, Jean Gill’s “A Certain Shade of Red,” replete with historical detail and symbolism, is narrated by Death himself as he observes the famous painter, Tician (Titian), dying of pestilence, and at earlier moments in his life. Then, as now, political leaders make choices about public health vs. the economy; these passages hit home.

“The Repentant Thief” by Deborah Swift stars an Irish immigrant boy in 1645 Edinburgh who steals a coin and locket from a tenement he’s broken into and then, as plague spreads, worries he’s brought God’s wrath down on his family. Historical atmosphere, well-wrought characters, realistic dialogue, pertinent themes, and a great ending: they’re all here.

Demonstrating the state of health care at the time, Katherine Pym’s “Arrows that Fly in the Dark” takes the perspective of time-traveling youths who inhabit the bodies of a physician’s apprentices in 1665 London. They find their master’s techniques for protecting against plague distasteful and sometimes ridiculous.

Lastly, “778” by Melodie Winawer, a tale of regret and resilience, shows how the rapidly shifting political climate in 17th-century Mystras, Greece, affects everyone in a Turkish man’s household. The arrival of plague adds to the heightened tensions.

A wide-ranging, rich collection of human experiences, all contained in a collection of fewer than 200 pages. This was a personal purchase. Hope this post encourages others to check it out for themselves. You can watch the YouTube recording of the panel below.

Monday, October 12, 2020

A Wild Winter Swan by Gregory Maguire, a fairy-tale sequel set in 1960s NYC

New York at Christmastime can be an enchanting place.

With his newest literary fantasy, a sort-of sequel to Hans Christian Andersen's “Wild Swans” fairy

tale set in the 1960s, Maguire adds new facets of wonder to this locale.

Raised

by her stern Italian grandparents, Laura Ciardi is a lonely fifteen-year-old

recently expelled after retaliating against a school bully. Her main company is

their cook, the delightful Mary Bernice, and two friendly workmen repairing the

family brownstone before a big holiday feast.

There, Laura’s grandparents hope

to entice their rich Irish brother-in-law into investing in her Nonno’s

grocery, while Laura wants a guardian angel to rescue her from potential

boarding school in Montreal. Appearing instead on the roof, one stormy night,

is a dirty, bedraggled young man with a swan’s wing for an arm.

Hilarity and

awkwardness ensue as Laura tries to care for him and build him another

wing without anyone noticing. Sensitive portraits of generational conflict and

coming-of-age intertwine with whimsy as Maguire touchingly shows how people

invoke stories to help elucidate their complicated world.

A Wild Winter Swan was published last week by William Morrow/HarperCollins. I reviewed it for the 9/1/20 issue of Booklist (reprinted with permission). A number of Maguire's novels incorporate historical settings: Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister (17th-c Holland), Hiddensee (early 19th-c Germany), Mirror Mirror (16th-c Italy). It was a nice change to see an American setting used for this latest imaginative tale.

Saturday, October 03, 2020

The Dark Horizon by Liz Harris, a saga set between the two world wars in England and America

Spanning the post-WWI period through the Great Depression in England and America, Harris delivers an addictive saga reminiscent of early Barbara Taylor Bradford. The story follows the romance between two young people from different worlds and its dramatic fallout.

Lily Brown had met Robert Linford when she was a land girl working near his family’s Oxfordshire estate. Enraptured with one another, they marry and have a son, James, but Joseph Linford, the intimidating and stubborn family patriarch, schemes to split them up, since he thinks Lily is inappropriate wife material and only after Robert’s money.

Joseph is a villain with depth. As head of Linford & Sons, he oversees a company building new housing developments on London’s outskirts and knows that Robert, his son and future successor, will need a partner who bolsters his social position. While beautiful Lily is a devoted wife and mother, it’s true that her naivete, lack of education, and the resulting anxiety hold her back. After Robert and Lily are driven apart and forced to rebuild their lives separately, it leaves a question open about whether they will ever reunite, and how, especially with both unaware of the deceit underlying their split.

The novel journeys along with their well-developed coming-of-age stories, told in parallel, as they form ties with others that help them grow in confidence. The backdrop of early 20th-century Hampstead, a community in north London, is an original setting, and the Jewish tenements of New York’s Lower East Side are vibrantly animated.

Joseph is a villain with depth. As head of Linford & Sons, he oversees a company building new housing developments on London’s outskirts and knows that Robert, his son and future successor, will need a partner who bolsters his social position. While beautiful Lily is a devoted wife and mother, it’s true that her naivete, lack of education, and the resulting anxiety hold her back. After Robert and Lily are driven apart and forced to rebuild their lives separately, it leaves a question open about whether they will ever reunite, and how, especially with both unaware of the deceit underlying their split.

The novel journeys along with their well-developed coming-of-age stories, told in parallel, as they form ties with others that help them grow in confidence. The backdrop of early 20th-century Hampstead, a community in north London, is an original setting, and the Jewish tenements of New York’s Lower East Side are vibrantly animated.

The story zips along with emotional currents that make the book hard to put down. Harris also manages to navigate a path through a complicated plot maze at the end, wrapping up her tale in a satisfying manner while leaving room for future volumes in the Linford Saga.

The Dark Horizon was published by Heywood Press in 2020; I reviewed it for August's Historical Novels Review and will be reviewing the next book, The Flame Within, next month. The next book will focus on Alice, the wife of Thomas Linford, who plays a secondary role here.

Wednesday, September 16, 2020

Before the Crown by Flora Harding fictionalizes the royal courtship of Elizabeth II and Prince Philip

Tailor-made for enthusiasts of The Crown, Flora Harding’s novel explores the intricate courtship between Elizabeth II and her consort, Prince Philip, now 94 and 99 years old. They married in 1947 and who – as avid royal watchers know – recently celebrated the wedding of their granddaughter Beatrice. Both the show and the novel provide the convincing illusion of breaching the wall that separates these world-famous, ultimately unknowable people from the rest of us.

While it can be read as a prequel to the Netflix series, Before the Crown stands independently and shouldn’t be thought of as “fan fiction.” At its heart, it reveals a love story presented as both predestined (since Elizabeth’s heart is set on Philip as a teenager) and unlikely (due to their very different temperaments, and the political roadblocks in the way of their union).

Harding is an experienced historical novelist who previously wrote Elizabethan-era fiction as Pamela Hartshorne. Her research into this considerably more modern timeframe is as thorough as ever, and her multifaceted characters have well-developed interior lives. Elizabeth, the shy and steadily reliable elder daughter of King George VI, carefully hides her feelings for Philip, whom she’s adored for years, behind a polite reserve. Philip, an outgoing Greek prince and Royal Navy lieutenant uprooted from his home country at a young age, finds himself nudged toward Elizabeth by his maternal uncle, “Dickie” Mountbatten, who knows she’d be a great catch.

Philip enjoys his naval career and a social life in which he does as he pleases, but he comes to appreciate Elizabeth’s kindness and generosity of spirit. His initiation into royal life is rocky and complicated by his sisters’ marriage to prominent Germans (former SS officers, even) and his future in-laws’ antipathy toward him as a suitor. George VI is stuffy and tradition-bound, and it doesn’t help that Philip finds hunting a dull pastime. Eventually he must decide whether to continue to pursue Elizabeth, knowing how much his lifestyle will change if they marry. The scenes at Balmoral Castle, a favorite residence of their joint ancestor Queen Victoria, evoke the rustic beauty of the Scottish landscape as the pair get to know each other better.

For readers interested in imagining what it’s like to be part of the British royals’ inner circle, Before the Crown fulfills its promises. It’s satisfying escapism perfect for these stressful times.

Before the Crown will be published tomorrow (Thursday, Sept. 17th) as an ebook by One More Chapter/HarperCollins. The paperback will be out in December. Thanks to the publisher for access via NetGalley.

While it can be read as a prequel to the Netflix series, Before the Crown stands independently and shouldn’t be thought of as “fan fiction.” At its heart, it reveals a love story presented as both predestined (since Elizabeth’s heart is set on Philip as a teenager) and unlikely (due to their very different temperaments, and the political roadblocks in the way of their union).

Harding is an experienced historical novelist who previously wrote Elizabethan-era fiction as Pamela Hartshorne. Her research into this considerably more modern timeframe is as thorough as ever, and her multifaceted characters have well-developed interior lives. Elizabeth, the shy and steadily reliable elder daughter of King George VI, carefully hides her feelings for Philip, whom she’s adored for years, behind a polite reserve. Philip, an outgoing Greek prince and Royal Navy lieutenant uprooted from his home country at a young age, finds himself nudged toward Elizabeth by his maternal uncle, “Dickie” Mountbatten, who knows she’d be a great catch.

Philip enjoys his naval career and a social life in which he does as he pleases, but he comes to appreciate Elizabeth’s kindness and generosity of spirit. His initiation into royal life is rocky and complicated by his sisters’ marriage to prominent Germans (former SS officers, even) and his future in-laws’ antipathy toward him as a suitor. George VI is stuffy and tradition-bound, and it doesn’t help that Philip finds hunting a dull pastime. Eventually he must decide whether to continue to pursue Elizabeth, knowing how much his lifestyle will change if they marry. The scenes at Balmoral Castle, a favorite residence of their joint ancestor Queen Victoria, evoke the rustic beauty of the Scottish landscape as the pair get to know each other better.

For readers interested in imagining what it’s like to be part of the British royals’ inner circle, Before the Crown fulfills its promises. It’s satisfying escapism perfect for these stressful times.

Before the Crown will be published tomorrow (Thursday, Sept. 17th) as an ebook by One More Chapter/HarperCollins. The paperback will be out in December. Thanks to the publisher for access via NetGalley.

Saturday, September 12, 2020

The Forgotten Kingdom by Signe Pike continues an epic story of sixth-century Scotland

In the second book of her epic trilogy of sixth-century Scotland, Pike adeptly balances brutal power struggles and Celtic mysticism.

Languoreth, the determined heroine from The Lost Queen (2018), is now the longtime wife of the King of Strathclyde's likely heir and a mother of four. Distraught to have her husband and twin brother, Lailoken, on opposite sides of the Battle of Arderydd, Languoreth finds her world further devastated when her eight-year-old daughter, Angharad, who was away learning druidic ways from Lailoken, vanishes in the battle’s aftermath.

Pike interweaves their three narratives as they endure emotional losses and begin physical and inward-focused journeys to regain strength. Moving from the shaded depths of the Caledonian Wood to the Pictish kingdom in the Orkney Islands and beyond, the story delves into the beguiling religious and cultural lore of several ancient Scottish peoples.

This book doesn’t stand alone, but ongoing readers will relish the escape into Pike’s fully developed milieu while seeing its connections to Arthurian legend grow more prominent; among other aspects, Lailoken serves as a historical model for Merlin.

The Forgotten Kingdom will be published on September 15th by Atria/Simon & Schuster (488pp, hardcover and ebook). I reviewed it for the August issue of Booklist (reprinted with permission). I'd previously reviewed The Lost Queen two years ago. As mentioned, interested readers will likely want to start with book one, since it provides considerable context for the interpersonal relationships and power imbalances in this novel. I look forward to continuing the story later on. The author's website says that book three will be out in September 2023.

Saturday, September 05, 2020

Old Lovegood Girls by Gail Godwin spans four decades of female friendship

Beautifully evoking a longtime friendship’s transformative power, Godwin traces two women’s intellectual development and life decisions, and how they intertwine, across four decades.

In 1958, Meredith Grace (“Merry”) Jellicoe and Feron Hood are matched as roommates at Lovegood College, a two-year school for women in North Carolina. The daughter of tobacco farmers, Merry has a welcoming personality, and the college dean, Susan Fox, believes she’ll be a comforting influence on the guarded Feron, who had a troubled home life. She’s right. The two become close; both are talented writers, sharing deep conversations on literary approaches and reading each other’s stories. Envious of Merry’s writing fluency, Feron feels she can do even better and uses this emotion to push herself forward.

Old Lovegood Girls focuses on connections rather than competition, though, and in this and other aspects, it gracefully subverts the tropes that pervade fiction about women. Likewise, Lovegood College, one of those old-fashioned, rigid-seeming institutions with longstanding rituals and values, breaks away from stereotype. Dean Fox, for example, is a wonderful character, an open, nurturing administrator with a full inner life. After the girls’ first semester, tragedy forces Merry to return home and take up family responsibilities. She and Feron correspond sporadically and rarely meet, but their friendship is of the type where they know each other’s qualities so well (they stay in each other’s “reference aura,” as Feron expresses it) that they rely on each other as guides through life.

With an unhurried pace that enables characters to develop and mature, the story delves with eloquent wisdom into a wide swath of issues: love, grief, family relationships, the value of storytelling, even (in a way that feels slyly meta) the challenges of writing historical novels. It’s a fine example of introspective fiction, and an ideal read for these uneasy times.

In 1958, Meredith Grace (“Merry”) Jellicoe and Feron Hood are matched as roommates at Lovegood College, a two-year school for women in North Carolina. The daughter of tobacco farmers, Merry has a welcoming personality, and the college dean, Susan Fox, believes she’ll be a comforting influence on the guarded Feron, who had a troubled home life. She’s right. The two become close; both are talented writers, sharing deep conversations on literary approaches and reading each other’s stories. Envious of Merry’s writing fluency, Feron feels she can do even better and uses this emotion to push herself forward.

Old Lovegood Girls focuses on connections rather than competition, though, and in this and other aspects, it gracefully subverts the tropes that pervade fiction about women. Likewise, Lovegood College, one of those old-fashioned, rigid-seeming institutions with longstanding rituals and values, breaks away from stereotype. Dean Fox, for example, is a wonderful character, an open, nurturing administrator with a full inner life. After the girls’ first semester, tragedy forces Merry to return home and take up family responsibilities. She and Feron correspond sporadically and rarely meet, but their friendship is of the type where they know each other’s qualities so well (they stay in each other’s “reference aura,” as Feron expresses it) that they rely on each other as guides through life.

With an unhurried pace that enables characters to develop and mature, the story delves with eloquent wisdom into a wide swath of issues: love, grief, family relationships, the value of storytelling, even (in a way that feels slyly meta) the challenges of writing historical novels. It’s a fine example of introspective fiction, and an ideal read for these uneasy times.

Old Lovegood Girls was published by Bloomsbury this year; I read it from an Edelweiss e-copy and reviewed it for August's Historical Novels Review. I became interested in it after hearing the author interviewed by Jenna Blum at A Mighty Blaze on Facebook Live in May. The historical college setting was enticing, and the discussion about the novel's themes piqued my attention. I also love the cover.

Thursday, August 20, 2020

Spindle and Dagger by J. Anderson Coats depicts a woman's necessary charade in 12th-century Wales

Coats’ newest historical novel is a penetrating portrait of women’s resilience and how they work through violent trauma. It’s based around a historical incident likely unfamiliar to its intended young adult audience: the abduction of Nest of Deheubarth by her second cousin Owain, Prince of Powys, during the increasing conflict between Welshmen and the land’s Norman invaders. Nest was married to Gerald of Windsor, leader of the Norman forces.

The tale’s narrator is Elen, a richly complex fictional character. In 1109, Elen has solidified a place for herself in Owain’s warband as his nightly bedmate. Three years earlier, Owain and his men had attacked her family’s steading, killing her two sisters. Seeing no other alternative for survival, Elen healed Owain of his injury and declared—falsely—that Saint Elen would faithfully guard Owain’s life if he always kept her namesake close by. Owain believes in the saint’s protection, but his men are more dubious.

Tension remains high, evoking the political strain, and Owain augments it after his penteulu (right-hand man) is killed by the Normans, and he captures Nest and her three young children in revenge. This angers his father, Cadwgan ap Bleddyn, who fears paying the price for his hotheaded son’s act. Elen faces her own battles. The flashbacks to her earlier ordeal are delicately handled, and even now, Elen’s mind vies between the status quo—staying with Owain and remaining alive and cared for—and wanting to take a dagger and stab him. Elen desperately wants a female ally. While Owain’s stepmother, Isabel, proves hostile to the idea, Elen sees how Nest bravely endures her captivity and envisions how to escape her longtime charade.

This gritty tale of feminine strength deserves attention from all medieval history enthusiasts, from YAs through adults.

Spindle and Dagger was published by Candlewick in 2020; I'd reviewed it for August's Historical Novels Review based on a publisher-supplied ARC.

Some other notes:

- This novel is classified as YA, and the heroine is seventeen, I believe, but the themes are hardly juvenile. It would work well as a crossover novel, in the vein of Julie Berry's The Book of Dolssa and Elizabeth Wein's Code Name Verity. Along these lines, the cover art is attractive, yes, but it's clearly aimed at teen readers. Adult readers of historical novels shouldn't be dissuaded from picking it up by the art or the marketing category.

- I've been fascinating by the story of Nest of Deheubarth ever since reading Eleanor Fairburn's 1966 novel The Golden Hive, a biographical novel about her. Nest/Nesta has been called the "Helen of Wales" as she was a woman whose beauty supposedly drove men to war, but the reality was likely far different than the romanticized legend. Soon after I'd reviewed The Golden Hive for this blog in 2010, I'd received an email from the author, which was a nice surprise. As I recall, she had been debating finding a publisher to bring her work back into print, but this never happened. She died in 2015. I'd still love to see her work made more widely available. Getting back to the subject at hand, when Spindle and Dagger became available for review, I knew I'd have to read it.

- The author's earlier The Wicked and the Just is also set in medieval Wales, specifically the 13th century. It's on my list to read.

- You can find Spindle and Dagger on Goodreads, but be aware that many readers gave it a low rating because the e-ARC had more than the usual number of typos.

The tale’s narrator is Elen, a richly complex fictional character. In 1109, Elen has solidified a place for herself in Owain’s warband as his nightly bedmate. Three years earlier, Owain and his men had attacked her family’s steading, killing her two sisters. Seeing no other alternative for survival, Elen healed Owain of his injury and declared—falsely—that Saint Elen would faithfully guard Owain’s life if he always kept her namesake close by. Owain believes in the saint’s protection, but his men are more dubious.

Tension remains high, evoking the political strain, and Owain augments it after his penteulu (right-hand man) is killed by the Normans, and he captures Nest and her three young children in revenge. This angers his father, Cadwgan ap Bleddyn, who fears paying the price for his hotheaded son’s act. Elen faces her own battles. The flashbacks to her earlier ordeal are delicately handled, and even now, Elen’s mind vies between the status quo—staying with Owain and remaining alive and cared for—and wanting to take a dagger and stab him. Elen desperately wants a female ally. While Owain’s stepmother, Isabel, proves hostile to the idea, Elen sees how Nest bravely endures her captivity and envisions how to escape her longtime charade.

This gritty tale of feminine strength deserves attention from all medieval history enthusiasts, from YAs through adults.

Spindle and Dagger was published by Candlewick in 2020; I'd reviewed it for August's Historical Novels Review based on a publisher-supplied ARC.

Some other notes:

- This novel is classified as YA, and the heroine is seventeen, I believe, but the themes are hardly juvenile. It would work well as a crossover novel, in the vein of Julie Berry's The Book of Dolssa and Elizabeth Wein's Code Name Verity. Along these lines, the cover art is attractive, yes, but it's clearly aimed at teen readers. Adult readers of historical novels shouldn't be dissuaded from picking it up by the art or the marketing category.

- I've been fascinating by the story of Nest of Deheubarth ever since reading Eleanor Fairburn's 1966 novel The Golden Hive, a biographical novel about her. Nest/Nesta has been called the "Helen of Wales" as she was a woman whose beauty supposedly drove men to war, but the reality was likely far different than the romanticized legend. Soon after I'd reviewed The Golden Hive for this blog in 2010, I'd received an email from the author, which was a nice surprise. As I recall, she had been debating finding a publisher to bring her work back into print, but this never happened. She died in 2015. I'd still love to see her work made more widely available. Getting back to the subject at hand, when Spindle and Dagger became available for review, I knew I'd have to read it.

- The author's earlier The Wicked and the Just is also set in medieval Wales, specifically the 13th century. It's on my list to read.

- You can find Spindle and Dagger on Goodreads, but be aware that many readers gave it a low rating because the e-ARC had more than the usual number of typos.

Monday, June 29, 2020

A Perfect Explanation by Eleanor Anstruther, a riveting historical novel about a dysfunctional aristocratic family

Anstruther’s debut centers on a shocking truth from her family history. Her paternal grandmother Enid Campbell, descendant of the Earls of Argyll, sold her younger son Ian to her sister for £500, following Enid’s divorce and bitter custody battle. Having received her father’s permission to tell his story, and infusing it with details from public court records and private sources, the author brings us into her characters’ thoughts with unvarnished candor and lays bare their flaws alongside the burdens and cruelties of aristocratic life.

The novel volleys between the 1920s and 1964, with Enid in a Hampstead nursing home before a prospective family reunion with her daughter and Ian, who she hasn’t seen since she gave him up 25 years earlier. Here she ponders a “perfect explanation” for her life choices, some of which were outside her control.

Emotionally cold, Enid is impossible to like, which makes being within her head uncomfortable. However, as we learn about the context behind her terrible decisions, we come to deeply empathize. After her older brother’s death at Gallipoli, and her sister Joan a confirmed “spinster” (who lived with her lesbian partner), Enid’s mother pushes her to provide an heir. Married to Douglas Anstruther, a man she comes to detest, Enid produces a boy and a girl, but her son Fagus’s physical challenges make him a deficient option in their view, and she feels pressured to try again.

Enraptured by religion, particularly Christian Science, Enid never wanted to marry or be a mother; the inside perspective of her descent into postpartum depression, which spurs her to abandon her family, feels wrenching. We also experience the views of Finetta, Enid’s daughter, yet another victim of a broken system that neglects its female children’s mental health and values money above all. This eye-opening novel is moving and psychologically shrewd throughout.

A Perfect Explanation was published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt in February, and by Salt (in the UK) last year. I read it from NetGalley and reviewed it for the Historical Novels Review's May issue.

For more background on the facts behind the story, the Daily Mail published an interview with the author, published when the novel came out in the UK in 2019.

The novel volleys between the 1920s and 1964, with Enid in a Hampstead nursing home before a prospective family reunion with her daughter and Ian, who she hasn’t seen since she gave him up 25 years earlier. Here she ponders a “perfect explanation” for her life choices, some of which were outside her control.