The authors who write as A.J. MacKenzie are visiting the blog today with an essay on their experiences as historians now writing historical fiction. Welcome!

~

Writing about history:

Making the leap from non-fiction to novels

Making the leap from non-fiction to novels

A.J. MacKenzie

Between us, we had more than twenty published non-fiction books and numerous articles and conference papers under our belts before we published our first novel. So, how hard was it to make the transition from fact to fiction?

The answer – inevitably – is that it was easy in some ways and hard in others. A lot of our non-fiction work is quite narrative – for example, our book about the Battle of Crécy in 1346, The Road to Crécy, or our forthcoming book on the Poitiers campaign of 1356, or Morgen’s business history works – so we are still story-telling; just moving from one kind of story to another.

There’s no doubt that fiction is a lot more freeing to write. Of course historical fiction has to be historically accurate. Details like clothing and food and firearms and means of transport have to be got right. Actual historical events need to be reflected as people at the time would have seen and understood them. But within that framework, you can do anything you want. If there is a quiet period in the story, you can invent some incidents and accidents to fill the gap. And you don't have to provide footnotes for every event or conversation in the book!

No such luck in ‘real’ history. One of the constant problems when writing military history is, how to fill in the gaps. Someone famously observed that warfare is about 5 per cent terror and 95 per cent tedium, and from our observation that is just about true. How do you hold the reader’s attention when all the army did was march for fifteen miles from one place to another very similar place and make camp for the night?

One of our answers is to fall back on details of the daily routine. What did the country they marched through look like? What was the weather like? What obstacles, physical or otherwise, did they have to overcome? What food did they eat and how was it provided? Answering those kinds of questions puts the reader into the position of the marching soldiers and helps them to understand what those people were seeing and experiencing. And actually, as novelists, we are often doing much the same thing. The major difference is with non-fiction you have to have hard evidence of the conditions, weather, food and so on to back up your hypothesis.

Character is another area of difference, though again the gap is not so large as you might think. As historians, we have to form opinions of the characters we are writing about. Sometimes the ‘heroes’ of our narratives are unpleasant people. The Black Prince may have been brave and inspired loyalty in his men, but he was also an arrogant spendthrift who burned and plundered everywhere his army marched (the plunder probably helped pay his bills at home).

On the other hand, historical characters are often more ‘real’ than fictional ones, and you don’t have to work so hard to invent them. When we wanted an officer of Volunteers for The Body in the Ice, should we take the time and trouble to invent one? Or should we just import a real figure, Jane Austen’s brother Edward, who lived not far from Romney Marsh and was a captain of Volunteers? The decision was easy. Welcome aboard, Captain Austen; help yourself to a glass of madeira, and join the cast of characters.

We will probably always write a mixture of non-fiction and fiction. Writing fiction makes us better story-tellers; writing non-fiction keeps our research skills up to scratch. There is a boundary between the two types of writing that must be respected; but at the same time, like good neighbours, each type of writing reinforces and strengthens the other.

~

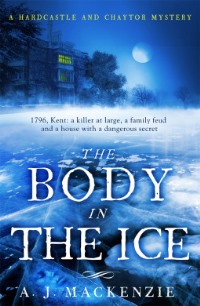

Christmas Day, Kent, 1796.

On the frozen fields of Romney Marsh stands New Hall; silent, lifeless, deserted. In its grounds lies an unexpected Christmas offering: a corpse, frozen into the ice of a horse pond.

It falls to the Reverend Hardcastle, justice of the peace at St Mary in the Marsh, to investigate. But with the victim's identity unknown, no murder weapon and no known motive, it seems like an impossible task. Working along with his trusted friend, Amelia Chaytor, and new arrival Captain Edward Austen, Hardcastle soon discovers there is more to the mystery than there first appeared.

With the arrival of an American family torn apart by war and desperate to reclaim their ancestral home, a French spy returning to the scene of his crimes, ancient loyalties and new vengeance combine to make Hardcastle and Mrs Chaytor's attempts to discover the secret of New Hall all the more dangerous.

The Body in the Ice, with its unique cast of characters, captivating amateur sleuths and a bitter family feud at its heart, is a twisting tale that vividly brings to life eighteenth-century Kent and draws readers into its pages.

About the author: A.J. MacKenzie is the pseudonym of Marilyn Livingstone and Morgen Witzel, a collaborative Anglo-Canadian husband-and-wife duo. Between them they have written more than twenty non-fiction and academic titles, with specialisms including management, medieval economic history and medieval warfare. The original idea for The Body…series came when the authors were living in Kent, when they often went down to Romney Marsh to enjoy the unique landscape and the beautiful old churches. The authors now live in Devon.

See also the authors' previous guest post about the atmospheric Romney Marsh.

No comments:

Post a Comment