Kaite Welsh’s debut, The Wages of Sin, is described as a “feminist Victorian crime novel.”

What this means: the story is seen from a female perspective and features women battling against gender inequality at a time, the Victorian era, when they weren’t accorded equal rights or treatment. Today’s women often forget what their forebears endured, but reading about Sarah Gilchrist’s experience will remind them.

As one of twelve “undergraduettes” at the university medical school in Edinburgh in 1892, Sarah faces disdainful treatment from her instructors, bullying from her male counterparts, and a definite lack of understanding from her stern Uncle Hugh and Aunt Emily, who treat her like an adolescent in need of discipline rather than a mature 27-year-old woman.

They feel their behavior is justified, based on Sarah’s traumatic past—which adds more facets to her character. Once a young woman in London society, she was sent away to Scotland to avoid ruining her younger sister’s marriage prospects. Her narrative doles out the details slowly, as if she must work up sufficient courage to reveal the truth.

The mystery subplot involves the death of a sex worker named Lucy. Four days before her corpse shows up on Sarah’s operating table, her neck with visible signs of bruising, she’d been a strong-willed, mouthy, and surprisingly literate patient at the charity clinic where Sarah volunteers.

When a novel opens mid-dissection, you know you’re in for a reading experience that oozes atmosphere—among other things. The differences between now and then are grimly emphasized. This is a time when women wore gloves for society outings, but took them off when wielding scalpels and digging into people’s innards. Late 19th-century Edinburgh is shown in all its contrasts, from the city’s elegant parlors to its opium dens and underground boxing venues. Life is clearly rough for the lower classes, with people aging long before their time. The plotline is intricate and not predictable, although one clue is essentially given away before it’s explicitly revealed later.

There are some hints of possible romance, too, with the love interest in question being one of Sarah’s superiors—a dicey situation in academia. The mysterious Professor Merchiston, one of her few supporters, clearly has an unusual past.

In the end, Sarah finds hope in female solidarity—despite the many examples of women holding back their own progress—and comes to see the plight all women share in this day and age, regardless of social status: “Why were we so desperate to believe that anything separated the people in drawing rooms from the people in the slums other than sheer luck?”

Although Sarah's a forward-thinking woman, the author avoids making her an overly feisty anachronism. The story remains in its temporal place, while its message rings out clearly. At a time when men in power seek to shut down women’s choices, the themes in The Wages of Sin couldn’t be more relevant.

The Wages of Sin was published by Pegasus in March in hardcover; thanks to the publisher for approving my Edelweiss access.

Friday, April 28, 2017

Monday, April 24, 2017

Elizabeth Ashworth's The de Lacy Inheritance, a standout medieval novel

Having some free time in between review assignments, I decided to pick up a novel that had been on my TBR for years (it was published in 2010). Then, after finishing, I regretted having waited so long.

Elizabeth Ashworth's The de Lacy Inheritance, which includes real-life figures from late 12-century Lancashire, should suit readers who seek out fiction with authentic medieval atmosphere, characters, and scenarios.

The physical book has been handsomely produced by Myrmidon; it's a pleasure to hold and flip through. One of the novel's two viewpoints is male, but if the damsel on the cover (depicting Johanna FitzEustace, the teenage heroine) and lace edging works to get the book into more readers' hands, then it's done its job.

In 1193, Richard FitzEustace has returned from Palestine, where he had accompanied King Richard on Crusade and had, sadly, contracted leprosy. In the opening scene, Richard (presumably a man in his twenties) kneels while his family's priest recites the Mass of Separation, which forbids him from entering a church, touching any well without his gloves on, or claiming his birthright. And more besides. It's a terrible fate even on top of his itchy affliction. In accordance with the mindset of medieval times, Richard accepts it, knowing that it's God's punishment for succumbing to temptation in the Holy Land: he'd fallen in love with an "Infidel" woman there.

Before leaving Halton Castle forever and taking refuge in a leper house, though, he's asked by his grandmother to visit her childless cousin, Sir Robert de Lacy, at Cliderhou Castle in Lancashire, to persuade him to name her as his heir. This way Sir Robert's lands will be kept within the family. Meanwhile, Richard's absence from Halton leaves his headstrong 14-year-old sister, Johanna, vulnerable. Her mother and uncle want her to marry an older man she finds repulsive.

I enjoyed seeing the warm friendship that develops between Richard and Sir Robert, and the ways in which villagers treat Richard with kindness while acknowledging his outcast status: they leave warm bread for him outside the hermit's cave near Cliderhou where he's taken up residence. The novel's conflict comes not just from Johanna's desperate situation but also because another man believes that he should be Sir Robert's rightful heir, rather than Richard.

Following a few intense, demanding reads, The de Lacy Inheritance was a welcome palate-cleanser of a book. There's nothing showy about it – it doesn't involve royalty or large-scale historical events – but the story moves along nicely throughout. I've noticed that British writers seem sparing in their use of commas when compared to Americans, which made for many seemingly run-on sentences, but I got used to the rhythm after a while.

This was Elizabeth Ashworth's first novel. Fortunately she's written many others since, all focused on medieval or Tudor times, and they're now on the TBR as well.

Elizabeth Ashworth's The de Lacy Inheritance, which includes real-life figures from late 12-century Lancashire, should suit readers who seek out fiction with authentic medieval atmosphere, characters, and scenarios.

The physical book has been handsomely produced by Myrmidon; it's a pleasure to hold and flip through. One of the novel's two viewpoints is male, but if the damsel on the cover (depicting Johanna FitzEustace, the teenage heroine) and lace edging works to get the book into more readers' hands, then it's done its job.

In 1193, Richard FitzEustace has returned from Palestine, where he had accompanied King Richard on Crusade and had, sadly, contracted leprosy. In the opening scene, Richard (presumably a man in his twenties) kneels while his family's priest recites the Mass of Separation, which forbids him from entering a church, touching any well without his gloves on, or claiming his birthright. And more besides. It's a terrible fate even on top of his itchy affliction. In accordance with the mindset of medieval times, Richard accepts it, knowing that it's God's punishment for succumbing to temptation in the Holy Land: he'd fallen in love with an "Infidel" woman there.

Before leaving Halton Castle forever and taking refuge in a leper house, though, he's asked by his grandmother to visit her childless cousin, Sir Robert de Lacy, at Cliderhou Castle in Lancashire, to persuade him to name her as his heir. This way Sir Robert's lands will be kept within the family. Meanwhile, Richard's absence from Halton leaves his headstrong 14-year-old sister, Johanna, vulnerable. Her mother and uncle want her to marry an older man she finds repulsive.

I enjoyed seeing the warm friendship that develops between Richard and Sir Robert, and the ways in which villagers treat Richard with kindness while acknowledging his outcast status: they leave warm bread for him outside the hermit's cave near Cliderhou where he's taken up residence. The novel's conflict comes not just from Johanna's desperate situation but also because another man believes that he should be Sir Robert's rightful heir, rather than Richard.

Following a few intense, demanding reads, The de Lacy Inheritance was a welcome palate-cleanser of a book. There's nothing showy about it – it doesn't involve royalty or large-scale historical events – but the story moves along nicely throughout. I've noticed that British writers seem sparing in their use of commas when compared to Americans, which made for many seemingly run-on sentences, but I got used to the rhythm after a while.

This was Elizabeth Ashworth's first novel. Fortunately she's written many others since, all focused on medieval or Tudor times, and they're now on the TBR as well.

Saturday, April 22, 2017

Writing about history: Making the leap from non-fiction to novels, a guest post by A.J. MacKenzie

The authors who write as A.J. MacKenzie are visiting the blog today with an essay on their experiences as historians now writing historical fiction. Welcome!

~

Writing about history:

Making the leap from non-fiction to novels

Making the leap from non-fiction to novels

A.J. MacKenzie

Between us, we had more than twenty published non-fiction books and numerous articles and conference papers under our belts before we published our first novel. So, how hard was it to make the transition from fact to fiction?

The answer – inevitably – is that it was easy in some ways and hard in others. A lot of our non-fiction work is quite narrative – for example, our book about the Battle of Crécy in 1346, The Road to Crécy, or our forthcoming book on the Poitiers campaign of 1356, or Morgen’s business history works – so we are still story-telling; just moving from one kind of story to another.

There’s no doubt that fiction is a lot more freeing to write. Of course historical fiction has to be historically accurate. Details like clothing and food and firearms and means of transport have to be got right. Actual historical events need to be reflected as people at the time would have seen and understood them. But within that framework, you can do anything you want. If there is a quiet period in the story, you can invent some incidents and accidents to fill the gap. And you don't have to provide footnotes for every event or conversation in the book!

No such luck in ‘real’ history. One of the constant problems when writing military history is, how to fill in the gaps. Someone famously observed that warfare is about 5 per cent terror and 95 per cent tedium, and from our observation that is just about true. How do you hold the reader’s attention when all the army did was march for fifteen miles from one place to another very similar place and make camp for the night?

One of our answers is to fall back on details of the daily routine. What did the country they marched through look like? What was the weather like? What obstacles, physical or otherwise, did they have to overcome? What food did they eat and how was it provided? Answering those kinds of questions puts the reader into the position of the marching soldiers and helps them to understand what those people were seeing and experiencing. And actually, as novelists, we are often doing much the same thing. The major difference is with non-fiction you have to have hard evidence of the conditions, weather, food and so on to back up your hypothesis.

Character is another area of difference, though again the gap is not so large as you might think. As historians, we have to form opinions of the characters we are writing about. Sometimes the ‘heroes’ of our narratives are unpleasant people. The Black Prince may have been brave and inspired loyalty in his men, but he was also an arrogant spendthrift who burned and plundered everywhere his army marched (the plunder probably helped pay his bills at home).

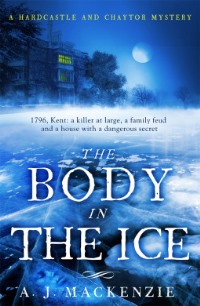

On the other hand, historical characters are often more ‘real’ than fictional ones, and you don’t have to work so hard to invent them. When we wanted an officer of Volunteers for The Body in the Ice, should we take the time and trouble to invent one? Or should we just import a real figure, Jane Austen’s brother Edward, who lived not far from Romney Marsh and was a captain of Volunteers? The decision was easy. Welcome aboard, Captain Austen; help yourself to a glass of madeira, and join the cast of characters.

We will probably always write a mixture of non-fiction and fiction. Writing fiction makes us better story-tellers; writing non-fiction keeps our research skills up to scratch. There is a boundary between the two types of writing that must be respected; but at the same time, like good neighbours, each type of writing reinforces and strengthens the other.

~

Christmas Day, Kent, 1796.

On the frozen fields of Romney Marsh stands New Hall; silent, lifeless, deserted. In its grounds lies an unexpected Christmas offering: a corpse, frozen into the ice of a horse pond.

It falls to the Reverend Hardcastle, justice of the peace at St Mary in the Marsh, to investigate. But with the victim's identity unknown, no murder weapon and no known motive, it seems like an impossible task. Working along with his trusted friend, Amelia Chaytor, and new arrival Captain Edward Austen, Hardcastle soon discovers there is more to the mystery than there first appeared.

With the arrival of an American family torn apart by war and desperate to reclaim their ancestral home, a French spy returning to the scene of his crimes, ancient loyalties and new vengeance combine to make Hardcastle and Mrs Chaytor's attempts to discover the secret of New Hall all the more dangerous.

The Body in the Ice, with its unique cast of characters, captivating amateur sleuths and a bitter family feud at its heart, is a twisting tale that vividly brings to life eighteenth-century Kent and draws readers into its pages.

About the author: A.J. MacKenzie is the pseudonym of Marilyn Livingstone and Morgen Witzel, a collaborative Anglo-Canadian husband-and-wife duo. Between them they have written more than twenty non-fiction and academic titles, with specialisms including management, medieval economic history and medieval warfare. The original idea for The Body…series came when the authors were living in Kent, when they often went down to Romney Marsh to enjoy the unique landscape and the beautiful old churches. The authors now live in Devon.

See also the authors' previous guest post about the atmospheric Romney Marsh.

Wednesday, April 19, 2017

A visual preview of the summer season in historical fiction

The area where I live in Illinois has suddenly become very green, and warm, and the spring semester's almost over. It feels like summer's almost here at last. If you're like me, your mind's been turning not just towards vacations and barbecues but also summer's crop of historical novels. Here are 12 books set to be released between May and August this year that looked especially enticing, and which have settings spanning four continents. The books themselves are published in the US, Canada, the UK, and Australia. This time, too, I remembered to add the Goodreads links!

The Ohio River, 1838: A young seamstress becomes enmeshed in secrets and deception when she's blackmailed into participating in the Underground Railroad. Touchstone, June 20; note that the UK title is The Floating Theatre. [see on Goodreads]

A multi-period novel, set in 1884 and a century later, about two women, a host of secrets, and the elegant New York City apartment residence known as The Dakota. Dutton, August 1. [see on Goodreads]

Forsyth, an Australian author, has recently specialized in re-imaginings of classic fairy tales, which are presented in a well-researched historical milieu. Her latest novel sets "Sleeping Beauty" amid the circle of pre-Raphaelite artists in Victorian times. Vintage Australia, July 3. [see on Goodreads]

Described as reminiscent of Possession and People of the Book, Kadish's newest novel tells the intertwined stories of women from two centuries: a Dutch immigrant serving as a scribe for a blind rabbi in Restoration London, and a modern historian specializing in Jewish history. HMH, June 6th. [see on Goodreads]

A sprawling story of politics, culture, and heritage focusing on the Ugandan people, beginning in 1750 and following a man's descendants as they try to evade a curse affecting their bloodline. Transit, May 16. [see on Goodreads, which also has reviews of the original edition, from Kenya.]

Part of McCrumb's Ballad series, set in the Appalachian region, fictionalizes the events behind the Greenbrier Ghost in late 19th-century West Virginia, happenings which have passed into American folklore. Atria, September 12. [see on Goodreads]

This second novel in the Kate Clifford mystery series is set in 1399 in York, England, a city on the brink of civil war. Meanwhile, Kate's mother shocks people by returning to town soon after her husband's mysterious death. Pegasus, June 6. [see on Goodreads]

Ross's debut novel fictionalizes the life of one of Canada's best-known pioneers and early memoirists, Englishwoman Susanna Moodie, in the Canadian wilderness of the 1830s. HarperAvenue, May. [see on Goodreads]

This novel of WWII begins in a Texas internment camp, where a Japanese diplomat's daughter first meets and falls in love with a young German-American man whose parents were unjustly imprisoned. The story later moves to Japan and the war in the Pacific. Washington Square, July 11. [see on Goodreads]

This family saga, the author's second novel after Daughter of Australia, follows a German immigrant family as they move from Pittsburgh to a farm in rural Pennsylvania in the early 20th century. Kensington, June 27. [see on Goodreads]

I enjoyed Wells' previous historical novel (The Wife's Tale) so much that I'm eagerly awaiting this new novel, a multi-period Gothic about an abandoned old house, WWII espionage, and a woman investigating her grandmother's hidden past. Penguin Australia, May 1st. [see on Goodreads]

First in a new mystery series set in the colony of Singapore in 1936, this novel features a young Chinese woman who turns sleuth after murder visits the country's Governor House. Constable, June 1. [see on Goodreads]

The Ohio River, 1838: A young seamstress becomes enmeshed in secrets and deception when she's blackmailed into participating in the Underground Railroad. Touchstone, June 20; note that the UK title is The Floating Theatre. [see on Goodreads]

A multi-period novel, set in 1884 and a century later, about two women, a host of secrets, and the elegant New York City apartment residence known as The Dakota. Dutton, August 1. [see on Goodreads]

Forsyth, an Australian author, has recently specialized in re-imaginings of classic fairy tales, which are presented in a well-researched historical milieu. Her latest novel sets "Sleeping Beauty" amid the circle of pre-Raphaelite artists in Victorian times. Vintage Australia, July 3. [see on Goodreads]

Described as reminiscent of Possession and People of the Book, Kadish's newest novel tells the intertwined stories of women from two centuries: a Dutch immigrant serving as a scribe for a blind rabbi in Restoration London, and a modern historian specializing in Jewish history. HMH, June 6th. [see on Goodreads]

A sprawling story of politics, culture, and heritage focusing on the Ugandan people, beginning in 1750 and following a man's descendants as they try to evade a curse affecting their bloodline. Transit, May 16. [see on Goodreads, which also has reviews of the original edition, from Kenya.]

Part of McCrumb's Ballad series, set in the Appalachian region, fictionalizes the events behind the Greenbrier Ghost in late 19th-century West Virginia, happenings which have passed into American folklore. Atria, September 12. [see on Goodreads]

This second novel in the Kate Clifford mystery series is set in 1399 in York, England, a city on the brink of civil war. Meanwhile, Kate's mother shocks people by returning to town soon after her husband's mysterious death. Pegasus, June 6. [see on Goodreads]

Ross's debut novel fictionalizes the life of one of Canada's best-known pioneers and early memoirists, Englishwoman Susanna Moodie, in the Canadian wilderness of the 1830s. HarperAvenue, May. [see on Goodreads]

This novel of WWII begins in a Texas internment camp, where a Japanese diplomat's daughter first meets and falls in love with a young German-American man whose parents were unjustly imprisoned. The story later moves to Japan and the war in the Pacific. Washington Square, July 11. [see on Goodreads]

This family saga, the author's second novel after Daughter of Australia, follows a German immigrant family as they move from Pittsburgh to a farm in rural Pennsylvania in the early 20th century. Kensington, June 27. [see on Goodreads]

I enjoyed Wells' previous historical novel (The Wife's Tale) so much that I'm eagerly awaiting this new novel, a multi-period Gothic about an abandoned old house, WWII espionage, and a woman investigating her grandmother's hidden past. Penguin Australia, May 1st. [see on Goodreads]

First in a new mystery series set in the colony of Singapore in 1936, this novel features a young Chinese woman who turns sleuth after murder visits the country's Governor House. Constable, June 1. [see on Goodreads]

Monday, April 17, 2017

Wilderness gothic: Sarah Maine's Beyond the Wild River

There was a beauty to this place, wild and unspoilt, vivid and sharp. Between the roar of the rapids there were stretches of exquisite calm water where the river widened along its course to form narrow lakes which sparkled with a piercing clarity...

Sarah Maine's work pays homage to the world's wild, remote places. Amid the forests of northwestern Ontario, thousands of miles from their home in the Scottish Borders, the characters of her second novel commune with nature: breathing in the scents of spruce and woodsmoke, catching and cooking fish for their suppers, and sleeping in tents along the banks of the Nipigon River.

Their relative isolation from all things familiar and safe heightens the sense of discovery but brings considerable risks. Several members of the expedition have unfinished business from five years ago that’s brought back into the open, and this time there's no running from it.

One might call this novel "wilderness gothic." As appropriate to the genre, we have a young ingénue as the heroine: Evelyn Ballantyre, age nineteen in 1893, relatively sheltered, and “lovely” (as we’re told a few times). Recently Evelyn’s father, a prominent Scottish philanthropist and investor, had misinterpreted an innocent act of hers – it appeared she was becoming too friendly with a servant – and she’s been paying the price.

Rather than continue to keep her cooped up at home as punishment, Charles Ballantyre decides to bring her on an excursion he'd planned to North America, to see the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and then to points north, across Lake Michigan and past the frontier town of Port Arthur (which will later become the city of Thunder Bay). There, they’ll fish in the “world’s finest trout stream.” Evelyn yearns to see more of the world, and for the chance to prove that she deserves to be treated as an adult.

To the surprise of both, one of their guides in the frontier turns out to be James Douglas, the former Ballantyre House stable hand who was accused of killing a poacher on their land five years earlier, and who had fled for parts unknown to save his neck. Back then, James and Evelyn had been good friends. Ever since, the sense of injustice toward him had weighed on her mind.

Their unlikely meeting isn’t the only coincidence in this atmospheric novel, whose story flows in a leisurely fashion for most of the book, then amps up the suspense toward the end – rather like waters in a peaceful stream gaining speed as they edge toward a waterfall. There are flashbacks here and there, and they’re not always smoothly inserted. However, the mystery itself is complex and interesting, with distinct aspects revealed little by little. Both Evelyn and her father know more about that night of the poacher’s murder than they dare reveal, to each other or to anyone else – including the friends accompanying them.

Maine crafts breathtaking turns of phrase that brings her settings alive. She recreates the era with a fine hand, too, with the Industrial Revolution bringing a revolution in technological developments. Scenes at Chicago’s White City explore these transformative changes. The author also offers period-appropriate commentary, through Evelyn’s eyes, on the land’s native peoples, who feature in exhibits at the World’s Fair – a shameful episode – but who negotiate with intelligence and foresight as their “old ways” are encroached upon.

Ironically, in this female-centered historical novel, it proves to be the men – James and Charles – who have the most layers to their personalities. But for readers with a yen to explore the “wild and unspoilt” lands depicted here, it takes a worthwhile journey.

Beyond the Wild River will be published tomorrow by Atria/Simon & Schuster in trade pb/ebook (I read it from an Edelweiss e-copy).

Added 4/19: Read more about Sarah Maine's inspiration for the novel in a post for the H is for History site, Researching the Nipigon River.

Sarah Maine's work pays homage to the world's wild, remote places. Amid the forests of northwestern Ontario, thousands of miles from their home in the Scottish Borders, the characters of her second novel commune with nature: breathing in the scents of spruce and woodsmoke, catching and cooking fish for their suppers, and sleeping in tents along the banks of the Nipigon River.

Their relative isolation from all things familiar and safe heightens the sense of discovery but brings considerable risks. Several members of the expedition have unfinished business from five years ago that’s brought back into the open, and this time there's no running from it.

One might call this novel "wilderness gothic." As appropriate to the genre, we have a young ingénue as the heroine: Evelyn Ballantyre, age nineteen in 1893, relatively sheltered, and “lovely” (as we’re told a few times). Recently Evelyn’s father, a prominent Scottish philanthropist and investor, had misinterpreted an innocent act of hers – it appeared she was becoming too friendly with a servant – and she’s been paying the price.

Rather than continue to keep her cooped up at home as punishment, Charles Ballantyre decides to bring her on an excursion he'd planned to North America, to see the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and then to points north, across Lake Michigan and past the frontier town of Port Arthur (which will later become the city of Thunder Bay). There, they’ll fish in the “world’s finest trout stream.” Evelyn yearns to see more of the world, and for the chance to prove that she deserves to be treated as an adult.

To the surprise of both, one of their guides in the frontier turns out to be James Douglas, the former Ballantyre House stable hand who was accused of killing a poacher on their land five years earlier, and who had fled for parts unknown to save his neck. Back then, James and Evelyn had been good friends. Ever since, the sense of injustice toward him had weighed on her mind.

Their unlikely meeting isn’t the only coincidence in this atmospheric novel, whose story flows in a leisurely fashion for most of the book, then amps up the suspense toward the end – rather like waters in a peaceful stream gaining speed as they edge toward a waterfall. There are flashbacks here and there, and they’re not always smoothly inserted. However, the mystery itself is complex and interesting, with distinct aspects revealed little by little. Both Evelyn and her father know more about that night of the poacher’s murder than they dare reveal, to each other or to anyone else – including the friends accompanying them.

Maine crafts breathtaking turns of phrase that brings her settings alive. She recreates the era with a fine hand, too, with the Industrial Revolution bringing a revolution in technological developments. Scenes at Chicago’s White City explore these transformative changes. The author also offers period-appropriate commentary, through Evelyn’s eyes, on the land’s native peoples, who feature in exhibits at the World’s Fair – a shameful episode – but who negotiate with intelligence and foresight as their “old ways” are encroached upon.

Ironically, in this female-centered historical novel, it proves to be the men – James and Charles – who have the most layers to their personalities. But for readers with a yen to explore the “wild and unspoilt” lands depicted here, it takes a worthwhile journey.

Beyond the Wild River will be published tomorrow by Atria/Simon & Schuster in trade pb/ebook (I read it from an Edelweiss e-copy).

Added 4/19: Read more about Sarah Maine's inspiration for the novel in a post for the H is for History site, Researching the Nipigon River.

Friday, April 14, 2017

Georgia Hunter's We Were the Lucky Ones, an unlikely WWII survival story

This debut novel recounts not only one but multiple harrowing tales of unlikely survival. It’s also an amazing piece of historical reconstruction, expertly translated into fiction.

As Hunter reveals at the start, fewer than 300 of the 30,000-plus Jewish residents of Radom, Poland, remained alive after WWII. Her grandfather and his four siblings were among them. Learning about her family’s Holocaust past as a teenager, she set out to uncover their stories: interviewing older relatives, tracing their paths across Europe and elsewhere, poring through archives for relevant facts.

Knowing the ultimate outcome, one may wonder whether the novel offers any suspense. In short, yes. The circumstances her characters endure are excruciatingly traumatic; that they manage to survive is thanks to a combination of resourceful planning, split-second decisions made under tremendous pressure, and random luck.

Also, there are numerous other people they care deeply about, and readers will anxiously hope that they survive as well. Many chapters end with a mini-cliffhanger, which seems over-the-top initially but does heighten tension.

The story has impressive breadth, spanning over six years and many countries around the globe as the Kurcs pursue separate quests for safety through a Nazi-darkened world. One can sense the terror faced by Mila, forced to hide her two-year-old daughter, Felicia, in a paper sack of fabric scraps when the Gestapo invades the factory where she works—and feel Felicia’s claustrophobic fear as well.

Genek and his wife Herta endure near-frozen conditions in a Siberian gulag, where their baby son is born. The author’s grandfather, Addy, an affable, talented musician, leaves Paris early on, but his planned voyage to Brazil is held up, and he remains consumed by worry over his family.

The novel is full of tangible details but has thriller-style pacing. Reading it is a consuming experience.

We Were the Lucky Ones was published by Viking in February and was reviewed in February's Historical Novels Review. The UK publisher is Allison & Busby. Read more about the author's background and multi-year quest to track her family's story at her website.

As Hunter reveals at the start, fewer than 300 of the 30,000-plus Jewish residents of Radom, Poland, remained alive after WWII. Her grandfather and his four siblings were among them. Learning about her family’s Holocaust past as a teenager, she set out to uncover their stories: interviewing older relatives, tracing their paths across Europe and elsewhere, poring through archives for relevant facts.

Knowing the ultimate outcome, one may wonder whether the novel offers any suspense. In short, yes. The circumstances her characters endure are excruciatingly traumatic; that they manage to survive is thanks to a combination of resourceful planning, split-second decisions made under tremendous pressure, and random luck.

Also, there are numerous other people they care deeply about, and readers will anxiously hope that they survive as well. Many chapters end with a mini-cliffhanger, which seems over-the-top initially but does heighten tension.

The story has impressive breadth, spanning over six years and many countries around the globe as the Kurcs pursue separate quests for safety through a Nazi-darkened world. One can sense the terror faced by Mila, forced to hide her two-year-old daughter, Felicia, in a paper sack of fabric scraps when the Gestapo invades the factory where she works—and feel Felicia’s claustrophobic fear as well.

Genek and his wife Herta endure near-frozen conditions in a Siberian gulag, where their baby son is born. The author’s grandfather, Addy, an affable, talented musician, leaves Paris early on, but his planned voyage to Brazil is held up, and he remains consumed by worry over his family.

The novel is full of tangible details but has thriller-style pacing. Reading it is a consuming experience.

We Were the Lucky Ones was published by Viking in February and was reviewed in February's Historical Novels Review. The UK publisher is Allison & Busby. Read more about the author's background and multi-year quest to track her family's story at her website.

Tuesday, April 11, 2017

Kathy Lynn Emerson's Murder in the Merchant's Hall, a detailed portrait of Elizabethan-era daily life

Back in 2015, I wrote a post, Tudor Fiction without the Famous, that collected Tudor historical novels about lesser-known or fictional characters, and which didn’t take place at court. As Kathy Lynn Emerson mentioned in the comments, her Mistress Jaffrey series fits this description. Book two, Murder in the Merchant’s Hall, has sat on my virtual TBR for too long, and I’m glad I finally had the chance to read it.

The heroine, Rosamond Jaffrey, was called upon in the past to do some work for Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth I’s spymaster, and he appears briefly in one scene. Primarily, though, the novel concerns itself with life among the gentry and merchant class in greater London and Kent, with a brief sojourn to Cambridge, where Rosamond’s husband is a student.

In London in autumn 1583, Godlina Walkenden stands accused of murdering her brother-in-law, mercer Hugo Hackett. She had discovered his body the night after arguing with him; she’d refused to marry the elderly Italian merchant Hugo wanted for her, claiming her would-be husband was “steeped in vice.” Lina’s half-sister Isolde wants her to suffer for her crime, but Lina claims not to have killed Hugo.

Lina quietly makes her way to Leigh Abbey in Kent, the residence of Susanna, Lady Appleton, where she’d been educated as a young girl. She hopes Susanna and her foster daughter, Rosamond, Lina’s childhood friend, can prove her innocence. (For those not in the know, Susanna was the heroine of another long-running mystery series by Emerson.) As Lina thinks: “Rosamond always knew what to do. Sometimes it was the wrong thing, but she was never at a loss when it came to making plans.”

That’s a fair description. A young woman of means whose past decisions have caused trouble for her family, Rosamond can be hard to take at times. She’s multilingual, very clever and knows it, and a master of disguises, which she uses a-plenty in her sleuthing. Rosamond also doesn’t value her devoted husband, Rob, as much as she should. She has some maturing to do, so it’s rewarding to see the scenes with their growing closeness. Lina’s a flawed character herself, and as the plot unravels, her foolish decisions become more obvious. For one, she’s infatuated with her would-be husband’s smooth-talking nephew, Tommaso.

If liking your protagonists is a necessity, you may not warm to this novel. That’s not a deal-breaker for me, though; characters’ realistic attitudes and behavior are more important, and I did find Rosamond and Lina realistic. The novel’s best part is its rich portrait of Elizabethan daily life. If you’ve ever wondered about various modes of transport during this era, requirements for the attire of Cambridge undergraduates, or the benefits of being a silkwoman in Tudor-era London, you’ll thoroughly revel in the atmosphere of this book.

Murder in the Merchant's Hall was published in 2015 by Severn House (I received access via NetGalley).

The heroine, Rosamond Jaffrey, was called upon in the past to do some work for Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth I’s spymaster, and he appears briefly in one scene. Primarily, though, the novel concerns itself with life among the gentry and merchant class in greater London and Kent, with a brief sojourn to Cambridge, where Rosamond’s husband is a student.

In London in autumn 1583, Godlina Walkenden stands accused of murdering her brother-in-law, mercer Hugo Hackett. She had discovered his body the night after arguing with him; she’d refused to marry the elderly Italian merchant Hugo wanted for her, claiming her would-be husband was “steeped in vice.” Lina’s half-sister Isolde wants her to suffer for her crime, but Lina claims not to have killed Hugo.

Lina quietly makes her way to Leigh Abbey in Kent, the residence of Susanna, Lady Appleton, where she’d been educated as a young girl. She hopes Susanna and her foster daughter, Rosamond, Lina’s childhood friend, can prove her innocence. (For those not in the know, Susanna was the heroine of another long-running mystery series by Emerson.) As Lina thinks: “Rosamond always knew what to do. Sometimes it was the wrong thing, but she was never at a loss when it came to making plans.”

That’s a fair description. A young woman of means whose past decisions have caused trouble for her family, Rosamond can be hard to take at times. She’s multilingual, very clever and knows it, and a master of disguises, which she uses a-plenty in her sleuthing. Rosamond also doesn’t value her devoted husband, Rob, as much as she should. She has some maturing to do, so it’s rewarding to see the scenes with their growing closeness. Lina’s a flawed character herself, and as the plot unravels, her foolish decisions become more obvious. For one, she’s infatuated with her would-be husband’s smooth-talking nephew, Tommaso.

If liking your protagonists is a necessity, you may not warm to this novel. That’s not a deal-breaker for me, though; characters’ realistic attitudes and behavior are more important, and I did find Rosamond and Lina realistic. The novel’s best part is its rich portrait of Elizabethan daily life. If you’ve ever wondered about various modes of transport during this era, requirements for the attire of Cambridge undergraduates, or the benefits of being a silkwoman in Tudor-era London, you’ll thoroughly revel in the atmosphere of this book.

Murder in the Merchant's Hall was published in 2015 by Severn House (I received access via NetGalley).

Friday, April 07, 2017

Book review: Stacia Pelletier's The Half Wives, set in late 19th-century San Francisco

Jack Plageman would have turned sixteen on May 22, 1897. However, tragically, he'd died in his crib on his second birthday. His parents’ lives haven’t been the same since. The observance of the sad anniversary takes the form of a ritual – an annual visit, timed precisely for 2pm, to San Francisco’s city cemetery, preceded by the replanting of a small garden around his tombstone. Nobody dares to change this.

That is, until this year, when the patterns are disrupted. All the characters come together at last, and long-concealed secrets spill forth.

The chapters in this finely tuned novel about grief, interpersonal connections, and the long journey toward independence revolve among four viewpoints. Henry Plageman, Jack’s father, is a former Lutheran minister turned hardware store owner. Stuck in the Golden Gate police station overnight after disturbing the peace at a local meeting, he needs to get himself out before 2pm, when he’s due to meet his wife. The cemetery where Jack’s buried sits on prime California real estate, overlooking the Golden Gate strait, and it’s a potter’s field: mostly immigrants and the destitute are interred there. When locals had proposed that the graves be moved elsewhere, Henry had made his objections loudly known.

Henry’s wife, Marilyn, who’s emotionally estranged from him yet tied to him via Jack, tries to drown her grief in endless charity work, but never succeeds, and doesn’t really want to. The third and fourth perspectives are those of Lucy Christensen, Henry’s secret lover, who misses him greatly but needs to break things off for her own sanity; and her lively eight-year-old daughter, Anna (nicknamed Blue), Henry’s only living child, who adores her father even though he sees them only rarely.

The Half Wives has three aspects that may take potential readers aback, even those who seek out literary fiction. The dialogue uses dashes instead of quotation marks; the plot of this 320-page book spans a mere six hours; and the perspectives of Henry, Marilyn, and Lucy are told in the second person. (Still with me?) This latter choice is startling, and I found it difficult to process at first. Fortunately, the pronoun difficulties mostly fell away after the first few chapters, and the use of “you” served to enhance the effect of characters going through the motions, rather than actively participating in their own lives.

The novel moves smoothly among the four viewpoints, and between present-day events and people’s memories about their moments of happiness and heartache. Pelletier provides poignant insight into the odd dependent relationship between Lucy and Marilyn that directs their lives, even though they’ve never met, and Marilyn doesn’t know of Lucy’s existence. Henry can’t bring himself to leave either woman, though it’s clear that his avoiding that decision has wrought its own set of consequences.

Henry’s also oblivious to the reality of Lucy’s situation, which she knows.

He loves your humble cottage by the sea. He used to call it home. Even though he never spent a full night inside. He adored its cleanliness, its unpretentiousness. Its separation from the everyday.

His everyday. Not yours. He never saw you scrub a floorboard. But you did scrub them.

The questions of whether Lucy can get up the courage to leave him, and how, create some compelling moments.

Although the characters are the focus, the historical setting, the “Outside Lands” of northwestern San Francisco – stunning yet remote, decades before the Golden Gate Bridge’s construction – is critical. The story emphasizes how the city treats its orphaned and poor residents, from childhood until after death.

Recommended for literary fiction readers who don’t mind taking their time or making some mental adjustments to the unusual style. It’s well worth it.

The Half Wives was published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt on Tuesday in hardcover and ebook; thanks to the publisher for sending the review copy.

That is, until this year, when the patterns are disrupted. All the characters come together at last, and long-concealed secrets spill forth.

The chapters in this finely tuned novel about grief, interpersonal connections, and the long journey toward independence revolve among four viewpoints. Henry Plageman, Jack’s father, is a former Lutheran minister turned hardware store owner. Stuck in the Golden Gate police station overnight after disturbing the peace at a local meeting, he needs to get himself out before 2pm, when he’s due to meet his wife. The cemetery where Jack’s buried sits on prime California real estate, overlooking the Golden Gate strait, and it’s a potter’s field: mostly immigrants and the destitute are interred there. When locals had proposed that the graves be moved elsewhere, Henry had made his objections loudly known.

Henry’s wife, Marilyn, who’s emotionally estranged from him yet tied to him via Jack, tries to drown her grief in endless charity work, but never succeeds, and doesn’t really want to. The third and fourth perspectives are those of Lucy Christensen, Henry’s secret lover, who misses him greatly but needs to break things off for her own sanity; and her lively eight-year-old daughter, Anna (nicknamed Blue), Henry’s only living child, who adores her father even though he sees them only rarely.

The Half Wives has three aspects that may take potential readers aback, even those who seek out literary fiction. The dialogue uses dashes instead of quotation marks; the plot of this 320-page book spans a mere six hours; and the perspectives of Henry, Marilyn, and Lucy are told in the second person. (Still with me?) This latter choice is startling, and I found it difficult to process at first. Fortunately, the pronoun difficulties mostly fell away after the first few chapters, and the use of “you” served to enhance the effect of characters going through the motions, rather than actively participating in their own lives.

The novel moves smoothly among the four viewpoints, and between present-day events and people’s memories about their moments of happiness and heartache. Pelletier provides poignant insight into the odd dependent relationship between Lucy and Marilyn that directs their lives, even though they’ve never met, and Marilyn doesn’t know of Lucy’s existence. Henry can’t bring himself to leave either woman, though it’s clear that his avoiding that decision has wrought its own set of consequences.

Henry’s also oblivious to the reality of Lucy’s situation, which she knows.

He loves your humble cottage by the sea. He used to call it home. Even though he never spent a full night inside. He adored its cleanliness, its unpretentiousness. Its separation from the everyday.

His everyday. Not yours. He never saw you scrub a floorboard. But you did scrub them.

The questions of whether Lucy can get up the courage to leave him, and how, create some compelling moments.

Although the characters are the focus, the historical setting, the “Outside Lands” of northwestern San Francisco – stunning yet remote, decades before the Golden Gate Bridge’s construction – is critical. The story emphasizes how the city treats its orphaned and poor residents, from childhood until after death.

Recommended for literary fiction readers who don’t mind taking their time or making some mental adjustments to the unusual style. It’s well worth it.

The Half Wives was published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt on Tuesday in hardcover and ebook; thanks to the publisher for sending the review copy.

Monday, April 03, 2017

My Last Lament by James William Brown, a novel of 1940s Greece

Aliki, a teenager in a northeastern Greek village in the 1940s, has an innate talent for singing dirge-poems honoring the deceased. After her father is executed by German soldiers, she’s taken in by Chrysoula, a neighbor woman with a son, Takis, who may be mentally ill.

Aliki grows close to Stelios, the young Greek Jewish man Chrysoula hides in her basement with his mother, and their bond makes Takis jealous. Then their household is betrayed, and violence erupts, forcing the trio into political chaos as civil war tears the country apart and Communist guerrillas roam the streets.

Because their characterizations are rather flat, Aliki and Stelios’ love story doesn’t attain the emotional heights it reaches for; the book’s gripping final chapters, however, have undeniable power. Aliki’s dry humor is entertaining as she records her life story on cassette for a modern American ethnographer.

Full of details on folk traditions, like shadow-puppet theater and ritual laments, Brown’s novel should entice readers curious about Greek history and culture and WWII enthusiasts seeking a new angle on the era.

My Last Lament is published tomorrow in hardcover and ebook by Berkley, and this review was submitted for Booklist's 3/1 issue.

Some more notes:

- It's a great concept for a novel. Even though the epic love story aspect didn't quite deliver for me, I appreciated the unique setting and all details on Greek culture. The WWII era is still immensely popular as a historical fiction setting, yet few authors have written about its effects on Greece and its people.

- This is Brown's second novel. His debut, Blood Dance (see the review from Publishers Weekly), published in 1993, focused on the women in a Greek village in the early 20th century. According to his bio, he lived and taught in Greece for a decade.

- Gorgeous cover! It's one of my favorites for the year: simple yet effective.

Aliki grows close to Stelios, the young Greek Jewish man Chrysoula hides in her basement with his mother, and their bond makes Takis jealous. Then their household is betrayed, and violence erupts, forcing the trio into political chaos as civil war tears the country apart and Communist guerrillas roam the streets.

Because their characterizations are rather flat, Aliki and Stelios’ love story doesn’t attain the emotional heights it reaches for; the book’s gripping final chapters, however, have undeniable power. Aliki’s dry humor is entertaining as she records her life story on cassette for a modern American ethnographer.

Full of details on folk traditions, like shadow-puppet theater and ritual laments, Brown’s novel should entice readers curious about Greek history and culture and WWII enthusiasts seeking a new angle on the era.

My Last Lament is published tomorrow in hardcover and ebook by Berkley, and this review was submitted for Booklist's 3/1 issue.

Some more notes:

- It's a great concept for a novel. Even though the epic love story aspect didn't quite deliver for me, I appreciated the unique setting and all details on Greek culture. The WWII era is still immensely popular as a historical fiction setting, yet few authors have written about its effects on Greece and its people.

- This is Brown's second novel. His debut, Blood Dance (see the review from Publishers Weekly), published in 1993, focused on the women in a Greek village in the early 20th century. According to his bio, he lived and taught in Greece for a decade.

- Gorgeous cover! It's one of my favorites for the year: simple yet effective.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)