Sara Poole's historical thriller The Borgia Betrayal begins with a poisoning, not an uncommon occurrence during the deadly power games of the Italian Renaissance, but two things set it apart. First, the perpetrator is a woman, Pope Alexander VI's court poisoner Francesca Giordano, and she seems – almost – to have compassion for the poor fellow who dies. Keeping her boss safe is her mission, and she'll do what she has to.

For her newest assignment, Francesca must find a discreet way of killing off Cardinal della Rovere, the Borgia pope's main rival. The story is hastened forward by several subplots that seem, at first, to be distractions from the main event.

While Borgia fights to keep Spain as a firm ally against the unruly French, Spain pressures him to break off his daughter Lucrezia's betrothal to Giovanni Sforza of Milan and to banish the Jews from Rome. He doesn't plan to do either. Rumors are spreading about the impending arrival of the fanatical monk from Florence, Savonarola. Amid the political tumult, Francesca refuses to abandon her personal quest: killing the mad priest, Bernando Morozzi, who masterminded her father's death.

Francesca fancies herself an outcast, an unnatural woman who enjoys her job a little too much and doesn't want the darkness inside her to touch anyone else. Although it's true that most people around the Vatican fear her (for good reason), she has more friends than she thinks. Among them are the handsome glassmaker she won't let herself get close to; her fellow members of the Lux, a secret society of free-thinkers; and her lover Cesare Borgia, the pope's son, whose lusts and dark leanings match her own.

Poole's depiction of Cesare is refreshing and suitably complex. Just seventeen in the year 1493, Cesare is more than just a power-hungry, immoral adolescent. He truly cares for Francesca, and their developing relationship – as well as his with his father – will be worth watching in future books.

Francesca's first-person voice has a sarcastic directness that comes as a nice change in an era where one's feelings are best kept hidden. Despite the many tangled strands of the plot, the narrative speeds along smoothly, and the author displays an intimate familiarity with this dangerous time and place. The Borgia Betrayal is second in a series after Poison. It works well as a standalone, although there are enough intriguing references to events from the first book for newcomers to regret not having read it.

The Borgia Betrayal was published by St. Martin's Griffin in June at $14.99 ($16.99 in Canada) in trade paperback (389pp, plus bonus material including an author interview, historical essay, and timeline).

Interested in winning a copy for yourself? I have one up for grabs. To enter, leave a comment on this post. Deadline Friday, September 9th. This contest is open internationally. Good luck!

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Monday, August 29, 2011

Bits and pieces

Thanks to whoever chose to nominate this site for "best historical fiction blog" in the Book Blogger Appreciation Week annual awards. It's much appreciated, and congrats to my fellow nominees. If anyone's curious, here are the posts I selected for the judging. At least I think they're what I put down. The fall semester started a week ago and I'm lucky I know which way is up.

And for some historical novel deals, from Publishers Marketplace's Lunch Deluxe reports:

Linda Holeman's untitled book, pitched as 'Anna Karenina meets Downton Abbey', and set in 1861 Imperialist Russia in the aftermath of the Emancipation of the Serfs, a sweeping tale of how the political turmoil of the country affects one landowner's family, to Anne Collins at Random House Canada, in a very nice deal, in a two-book deal, for publication in spring 2012, by Sarah Heller at the Helen Heller Agency. [and I'd actually gone looking to her website when putting together my Canadian preview to see if she had a new book coming out - ask and ye shall receive]

Stephanie Dray's DAUGHTER OF THE NILE, the final book in the author's trilogy tracing the ambitious and passionate life of Selene -- daughter of Cleopatra, princess of Egypt, Queen of Mauretania, and disciple of Isis, to Cindy Hwang at Berkley, by Jennifer Schober at Spencerhill Associates (NA). [I'll be reading this; here's my review of book one.]

Carlene Bauer's FRANCES & BERNARD, an epistolary novel imagining the friendship, discussions of faith and art, and bittersweet romance between two writers in late 1950s New York, inspired by Flannery O'Connor and Robert Lowell, to Jenna Johnson at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, in a pre-empt, for publication in Fall 2012, by PJ Mark at Janklow & Nesbit (World English).

Author of WILDFLOWER HILL Kimberley Freeman's ISABELLA'S GIFT, spanning centuries about two women connected by a secret hidden in the walls of a family lighthouse, to Sally Kim for Touchstone, for publication in summer 2012, by Airlie Lawson at Hachette Australia.

Christine Wade's THE BOWER WIFE, a retelling of the first American folk tale in which a woman's husband mysteriously vanishes, abandoning her and her children on their farm at the foot of the Catskills, and a dark story begins to circulate in the small frontier community near which the family lives, as the Revolutionary War fast approaches, to Sarah Durand at Atria, by Eleanor Jackson at Markson Thoma (World). [folk tale about the early Revolutionary period? I'm there]

The Darling Strumpet and The September Queen author Gillian Bagwell's MY LADY BESS, based on the life of Bess of Hardwick, 1527-1608, the formidable four-times widowed Tudor dynasty who began life in genteel poverty and ended as the richest and most powerful woman in England after Queen Elizabeth; built Chatsworth House and Hardwick Hall; and is the forebear of numerous noble lines including the current royal family of Britain, to Kate Seaver at Berkley, by Kevan Lyon at Marsal Lyon Literary Agency (NA). [about time for a new fictional retelling of Bess of Hardwick's life!]

- X is for Xenia, my review of Jane Alison's The Love-Artist.

- Daughters of Summer, a visual preview of summer 2011 books that shows a popular title trend...

- My review of Carol K. Carr's India Black, which was as fun to write as the book was to read.

- The interview I conducted with Sonia Gensler about her spooky ghost story The Revenant.

- My compilation of historical fiction picks at BEA 2011. I've read just one of these so far, Stella Tillyard's Tides of War, which was a Booklist review assignment.

And for some historical novel deals, from Publishers Marketplace's Lunch Deluxe reports:

Linda Holeman's untitled book, pitched as 'Anna Karenina meets Downton Abbey', and set in 1861 Imperialist Russia in the aftermath of the Emancipation of the Serfs, a sweeping tale of how the political turmoil of the country affects one landowner's family, to Anne Collins at Random House Canada, in a very nice deal, in a two-book deal, for publication in spring 2012, by Sarah Heller at the Helen Heller Agency. [and I'd actually gone looking to her website when putting together my Canadian preview to see if she had a new book coming out - ask and ye shall receive]

Stephanie Dray's DAUGHTER OF THE NILE, the final book in the author's trilogy tracing the ambitious and passionate life of Selene -- daughter of Cleopatra, princess of Egypt, Queen of Mauretania, and disciple of Isis, to Cindy Hwang at Berkley, by Jennifer Schober at Spencerhill Associates (NA). [I'll be reading this; here's my review of book one.]

Carlene Bauer's FRANCES & BERNARD, an epistolary novel imagining the friendship, discussions of faith and art, and bittersweet romance between two writers in late 1950s New York, inspired by Flannery O'Connor and Robert Lowell, to Jenna Johnson at Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, in a pre-empt, for publication in Fall 2012, by PJ Mark at Janklow & Nesbit (World English).

Author of WILDFLOWER HILL Kimberley Freeman's ISABELLA'S GIFT, spanning centuries about two women connected by a secret hidden in the walls of a family lighthouse, to Sally Kim for Touchstone, for publication in summer 2012, by Airlie Lawson at Hachette Australia.

Christine Wade's THE BOWER WIFE, a retelling of the first American folk tale in which a woman's husband mysteriously vanishes, abandoning her and her children on their farm at the foot of the Catskills, and a dark story begins to circulate in the small frontier community near which the family lives, as the Revolutionary War fast approaches, to Sarah Durand at Atria, by Eleanor Jackson at Markson Thoma (World). [folk tale about the early Revolutionary period? I'm there]

The Darling Strumpet and The September Queen author Gillian Bagwell's MY LADY BESS, based on the life of Bess of Hardwick, 1527-1608, the formidable four-times widowed Tudor dynasty who began life in genteel poverty and ended as the richest and most powerful woman in England after Queen Elizabeth; built Chatsworth House and Hardwick Hall; and is the forebear of numerous noble lines including the current royal family of Britain, to Kate Seaver at Berkley, by Kevan Lyon at Marsal Lyon Literary Agency (NA). [about time for a new fictional retelling of Bess of Hardwick's life!]

Saturday, August 27, 2011

A Canadian historical fiction showcase, part 2

I've been getting a lot of visitors to my first visual preview of Canadian historical fiction so decided to do a followup. Most of these historical novels will be appearing in fall 2011.

In addition, no cover art is available for this one yet, so I haven't listed it below, but I wanted to make a special note of one book I'm highly anticipating. Michael Ennis (author of the fabulous Duchess of Milan) will have a new novel out in late January from McClelland & Stewart. A Most Beautiful Deception is a fact-based historical thriller set in the world of Niccolò Machiavelli and Leonardo da Vinci. Ennis isn't Canadian, but the novel doesn't appear to be published elsewhere.

Happy browsing. Did I miss any important titles? Let me know!

In a series of connected short stories spanning 1901 to 1999, DeGrace takes readers through a century of change in the company of a large cast of characters. The setting moves through the vast Canadian landscape, from early 20th-century Ontario to 1920s Montreal to Depression-era Saskatchewan and beyond. McArthur & Co., Sept.

The story of Molly Norton, the half-native daughter of the governor of Hudson's Bay Company in 18th-century Manitoba, and Samuel Hearne, the explorer she married. A sensitive rendering of a tragic clash of cultures that took place over two centuries ago. The characters are based on historical figures. HarperCollins Canada, March (it's already out, and my copy arrived in yesterday's mail).

The love triangle between novelist Victor Hugo; Hugo's long-suffering wife, Adèle; and Hugo's would-be friend, French journalist and literary critic Charles Sainte-Beuve, set during the reign of Napoleon III. HarperCollins Canada, Sept.; published in the UK in July by Serpent's Tail.

Maureen Jennings' Detective Murdoch mysteries set in late 19th-century Toronto are hugely popular in Canada. Season of Darkness, first in her new series, takes place in rural Shropshire a year into WWII. A detective who expected to be bored by his seemingly dull assignment finds himself investigating the death of a land girl. Read the review from the NY Times. McClelland & Stewart, Aug.

Another of Johnston's literary epics, this time set in late 19th-century Newfoundland, New Jersey, and North Carolina. When his personal circumstances turn sour, a man turns to his wealthy former Princeton classmate, George "Van" Vanderluyden, for help, and gets drawn into his deceitful net. (Van is based on George Washington Vanderbilt II, who constructed Biltmore.) Knopf Canada, Aug.

It's been four years since McKay's debut, The Birth House, her celebrated and bestselling novel about the trials of a determined young midwife in an early 20th-century Nova Scotia fishing village. Expect plenty of demand for The Virgin Cure, which was inspired by her great-great-grandmother's story. Moth grows up in the slums of New York's Bowery district, where she befriends a female physician and become wise to the cruel ways of the adult world. Knopf Canada, Oct; to be pub by HarperCollins US in Feb 2012.

The Forgetful Shore by Newfoundlander Trudy Morgan-Cole reveals the stories of two friends, closer than sisters, who grow up in a small coastal town in the early 20th century. Although they remain in touch after their adult lives diverge, their friendship abruptly changes when a long-held secret emerges. The author has also written novels about biblical women as well as The Violent Friendship of Esther Johnson, about a shadowy woman who was Jonathan Swift's good friend and possibly more. Breakwater, Sept.

Gayla Reid is a multi-award winning Australian-Canadian writer, and her latest work incorporates elements from the history of both countries. It tells the story of an Australian nurse longing for news of her Canadian lover, a volunteer on the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War. While she waits, she reveals her life story to her daughter. Cormorant, Aug.

Polish-Canadian writer Stachniak's third work of fiction is an epic historical novel about Catherine the Great's rise to power in mid-18th century Russia, as seen from the viewpoint of her servant, Varvara. The US publisher is gearing up for promotion already (my copy arrived last week) and I'm sure we'll be seeing much more of it this winter. Let's hope this means Russian settings are on the upswing. Doubleday Canada, Dec; also Bantam US, January, and Doubleday UK, January.

Vanderhaeghe, an author of significance in modern Canadian literature, presents his 3rd epic of the American and Canadian West in the late 19th century. The first two books in this loosely formed trilogy are The Englishman's Boy and The Last Crossing. McClelland & Stewart, Sept., and Atlantic Monthly (US), Jan.

In 1788, Lt. George Cartwright's trading expedition set out to make peaceful contact with the Beothuk, the native inhabitants of Newfoundland, in 1768. Literary historical adventure along the early Canadian frontier. Breakwater, Sept.

In addition, no cover art is available for this one yet, so I haven't listed it below, but I wanted to make a special note of one book I'm highly anticipating. Michael Ennis (author of the fabulous Duchess of Milan) will have a new novel out in late January from McClelland & Stewart. A Most Beautiful Deception is a fact-based historical thriller set in the world of Niccolò Machiavelli and Leonardo da Vinci. Ennis isn't Canadian, but the novel doesn't appear to be published elsewhere.

Happy browsing. Did I miss any important titles? Let me know!

In a series of connected short stories spanning 1901 to 1999, DeGrace takes readers through a century of change in the company of a large cast of characters. The setting moves through the vast Canadian landscape, from early 20th-century Ontario to 1920s Montreal to Depression-era Saskatchewan and beyond. McArthur & Co., Sept.

The story of Molly Norton, the half-native daughter of the governor of Hudson's Bay Company in 18th-century Manitoba, and Samuel Hearne, the explorer she married. A sensitive rendering of a tragic clash of cultures that took place over two centuries ago. The characters are based on historical figures. HarperCollins Canada, March (it's already out, and my copy arrived in yesterday's mail).

The love triangle between novelist Victor Hugo; Hugo's long-suffering wife, Adèle; and Hugo's would-be friend, French journalist and literary critic Charles Sainte-Beuve, set during the reign of Napoleon III. HarperCollins Canada, Sept.; published in the UK in July by Serpent's Tail.

Maureen Jennings' Detective Murdoch mysteries set in late 19th-century Toronto are hugely popular in Canada. Season of Darkness, first in her new series, takes place in rural Shropshire a year into WWII. A detective who expected to be bored by his seemingly dull assignment finds himself investigating the death of a land girl. Read the review from the NY Times. McClelland & Stewart, Aug.

Another of Johnston's literary epics, this time set in late 19th-century Newfoundland, New Jersey, and North Carolina. When his personal circumstances turn sour, a man turns to his wealthy former Princeton classmate, George "Van" Vanderluyden, for help, and gets drawn into his deceitful net. (Van is based on George Washington Vanderbilt II, who constructed Biltmore.) Knopf Canada, Aug.

It's been four years since McKay's debut, The Birth House, her celebrated and bestselling novel about the trials of a determined young midwife in an early 20th-century Nova Scotia fishing village. Expect plenty of demand for The Virgin Cure, which was inspired by her great-great-grandmother's story. Moth grows up in the slums of New York's Bowery district, where she befriends a female physician and become wise to the cruel ways of the adult world. Knopf Canada, Oct; to be pub by HarperCollins US in Feb 2012.

The Forgetful Shore by Newfoundlander Trudy Morgan-Cole reveals the stories of two friends, closer than sisters, who grow up in a small coastal town in the early 20th century. Although they remain in touch after their adult lives diverge, their friendship abruptly changes when a long-held secret emerges. The author has also written novels about biblical women as well as The Violent Friendship of Esther Johnson, about a shadowy woman who was Jonathan Swift's good friend and possibly more. Breakwater, Sept.

Gayla Reid is a multi-award winning Australian-Canadian writer, and her latest work incorporates elements from the history of both countries. It tells the story of an Australian nurse longing for news of her Canadian lover, a volunteer on the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War. While she waits, she reveals her life story to her daughter. Cormorant, Aug.

Polish-Canadian writer Stachniak's third work of fiction is an epic historical novel about Catherine the Great's rise to power in mid-18th century Russia, as seen from the viewpoint of her servant, Varvara. The US publisher is gearing up for promotion already (my copy arrived last week) and I'm sure we'll be seeing much more of it this winter. Let's hope this means Russian settings are on the upswing. Doubleday Canada, Dec; also Bantam US, January, and Doubleday UK, January.

Vanderhaeghe, an author of significance in modern Canadian literature, presents his 3rd epic of the American and Canadian West in the late 19th century. The first two books in this loosely formed trilogy are The Englishman's Boy and The Last Crossing. McClelland & Stewart, Sept., and Atlantic Monthly (US), Jan.

In 1788, Lt. George Cartwright's trading expedition set out to make peaceful contact with the Beothuk, the native inhabitants of Newfoundland, in 1768. Literary historical adventure along the early Canadian frontier. Breakwater, Sept.

Monday, August 22, 2011

A look at Karleen Koen's Before Versailles

Karleen Koen’s lush and literary fourth novel takes place over the six-month period, March through September 1661, when Louis XIV of France transformed himself into an absolute monarch. Reading it provides complete immersion into the elaborate rituals and gorgeous décor at the French royal court. While the atmosphere at the Château de Fontainebleau may seem light and carefree on the surface, however, cruel power games play out behind the scenes.

France’s greatest administrator, Cardinal Mazarin, has just died, and rival statesmen are moving in to fill the void. With the country’s recent civil wars (the Fronde) never far from his mind, 22-year-old King Louis must decide who pledges their true loyalty and who intrigues against him. The omniscient viewpoint ensures a comprehensive portrait of the place and time. Readers get to see the inner thoughts and motives of all the major players, from the worries and ambitions of the queen mother, Anne of Austria, to the lusty schemes of Catherine, Princess of Monaco, all without losing sight of the larger story.

As Louis solidifies his grip on the reins of power, he begins to understand that some choices simply aren’t open to him. Even a king can’t have everything he wants, especially if one of them is Henriette, his younger brother Philippe’s fun-loving and flirtatious wife. Fortunately, before the court erupts in scandal over their forbidden love affair, his eye turns to someone new.

Louise de la Baume le Blanc is a kind, gentle, and shy maid of honor, and in a court full of hidden agendas, Louis appreciates a woman who won’t play him false. Their connection is deep and passionate, and, as Koen alludes, on his side it will be temporary – but it feels no less poignant for that. Louise also has a curious streak. One day while out riding in the woods, she spies a boy wearing an iron mask, not realizing her quest to discover his secret has the potential to shake the kingdom.

With its richly decadent setting, Before Versailles is a dazzling feast for the visual imagination. The abundance of detail can be too much to take in all at once (you wouldn’t expect to see all of Fontainebleau in a single day, would you?) so prepare for a leisurely read. In addition, the novel is a skilled evocation of one man’s determination to take control of the land he was born to rule.

Before Versailles was published by Crown in late June at $26.00 / $31 in Canada (hardcover, 460pp).

France’s greatest administrator, Cardinal Mazarin, has just died, and rival statesmen are moving in to fill the void. With the country’s recent civil wars (the Fronde) never far from his mind, 22-year-old King Louis must decide who pledges their true loyalty and who intrigues against him. The omniscient viewpoint ensures a comprehensive portrait of the place and time. Readers get to see the inner thoughts and motives of all the major players, from the worries and ambitions of the queen mother, Anne of Austria, to the lusty schemes of Catherine, Princess of Monaco, all without losing sight of the larger story.

As Louis solidifies his grip on the reins of power, he begins to understand that some choices simply aren’t open to him. Even a king can’t have everything he wants, especially if one of them is Henriette, his younger brother Philippe’s fun-loving and flirtatious wife. Fortunately, before the court erupts in scandal over their forbidden love affair, his eye turns to someone new.

Louise de la Baume le Blanc is a kind, gentle, and shy maid of honor, and in a court full of hidden agendas, Louis appreciates a woman who won’t play him false. Their connection is deep and passionate, and, as Koen alludes, on his side it will be temporary – but it feels no less poignant for that. Louise also has a curious streak. One day while out riding in the woods, she spies a boy wearing an iron mask, not realizing her quest to discover his secret has the potential to shake the kingdom.

With its richly decadent setting, Before Versailles is a dazzling feast for the visual imagination. The abundance of detail can be too much to take in all at once (you wouldn’t expect to see all of Fontainebleau in a single day, would you?) so prepare for a leisurely read. In addition, the novel is a skilled evocation of one man’s determination to take control of the land he was born to rule.

Before Versailles was published by Crown in late June at $26.00 / $31 in Canada (hardcover, 460pp).

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Guest post from Elisabeth Storrs: Snail Mail, Rome and Ursula Le Guin

I'm so pleased to present this guest post from Elisabeth Storrs, whose excellent historical novel of ancient Etruria, The Wedding Shroud, I reviewed last December. While the paperback version is currently available only in Australia, it's newly out in ebook format worldwide and can be purchased on Amazon, iBookstore and Kobo. Visit her website for links.

Elisabeth's post will be of interest to writers as well as readers. How does a debut novelist approach a well-known author for an endorsement? Please read on!

Snail Mail, Rome and Ursula Le Guin

Old fashioned courtesy can go a long way. And so, too, can snail mail. When I requested Ursula Le Guin to endorse my novel I used both.

Last year my first novel, The Wedding Shroud, was published in Australia (and has now been released as an e-book world wide). The book is set in C5th BCE at a time when Rome was still scrapping for ascendancy over its Latin neighbours. The book compares the intolerant insular Romans with its enemies, the Etruscans, a people whose highly sophisticated civilisation spread throughout Italy and across the Mediterranean into northern Europe. My protagonist is a young Roman girl married to an Etruscan nobleman to seal a truce. Leaving behind a righteous society, she is determined to remain true to Roman virtues while living among the sinful Etruscans. Instead she finds herself tempted by a mystical, hedonistic culture which offers pleasure and independence to women.

As an unknown writer I faced the daunting task of gaining publicity and credibility amid a plethora of new releases in the market place. My publisher suggested I have the book endorsed by a well known author. Sounded like a great idea. Only problem was to find one who would do it!

My immediate thought was to find an historical fiction author whom I admired. There was no lack of these. I also thought it would be best if I could identify someone who was interested in the subject matter of my novel not just in history per se.

Around this time, a friend of mine mentioned that Ursula Le Guin’s Lavinia had been released to rave reviews. I was fascinated by this as I only knew her as the eminent author of amazing fantasy novels. I was also intrigued by the title of her book as I recognised it as the name of the wife of Aeneas, the hero of The Aeneid, an epic written by the Roman poet Vergil.

I read Lavinia and was transported back to a time when Rome was yet to be founded and a war weary Trojan wanderer fell in love with the daughter of Latium’s king. The character of Lavinia is not developed in The Aeneid but Ursula Le Guin created a complex woman whose love for a stranger started a war.

As a school girl I loved translating The Aeneid and it struck me that Ursula Le Guin must have a similar affection. In her Author’s Note I read how she had visited the area in Italy where ancient Latium was situated. Her delight in walking the same land upon which her characters had dwelt was clear. Her enthusiasm resonated with me. I also had dreams of standing in the ruins of Veii, the Etruscan city in which my novel is set.

I looked at Ursula Le Guin’s website and found that she was prepared to write blurbs for books but would only respond to letters i.e. snail mail. With a gentle sense of humour she also specified that overseas correspondents should include an international reply coupon if they expected a response due to the fact she would have to bear the costs of mailing a reply. As she personally answered her own correspondence this could take some time. In her own words ‘Silence means I'm sorry: Art is long, life is short, and I want to get on with my own book.’

On the premise of ‘she can only say no’ or more to the point - reply with silence, I wrote her a letter. In it I explained how much I enjoyed Lavinia because of my fondness for Vergil’s The Aeneid. I also provided a one page synopsis of my novel and explained how I, too, wished to walk upon ancient land in reality as well as in my imagination.

I have a vivid memory of hurrying to my local post office and asking for an international reply coupon before slipping the letter into the big red mailbox and crossing my fingers. To my utter astonishment, she responded only a few weeks later to say that she had always been fascinated by the Etruscans and would like to visit ancient Veii through reading my book. Imagine my excitement when she then agreed to endorse it! I still find it hard to believe she was gracious enough to reply let alone write a blurb.

Only Ursula Le Guin can tell why she was prepared to give her time and endorsement to an unknown Australian writer but in the end I believe that, in this world of Twitter, Facebook and email, the old fashioned courtesy of taking time to write and post a letter with a self addressed envelope and a reply coupon must have helped. It was also fate, too, because not longer after this Australia Post phased out international reply coupons. So maybe the Etruscan gods were smiling upon me. I’m certainly glad they did.

~Elisabeth Storrs

Elisabeth Storrs graduated from the University of Sydney in Arts Law, majoring in English and having studied Classics. She lives with her husband and two sons in Sydney and over the years has worked as a solicitor, corporate lawyer, senior manager and company secretary.

Elisabeth's first novel, The Wedding Shroud, is set in early Rome and Etruria, and was researched and written over a period of ten years. It is now available as an ebook world wide. She is currently writing the sequel which will be released by Pier 9 / Murdoch Books in 2012.

Elisabeth's post will be of interest to writers as well as readers. How does a debut novelist approach a well-known author for an endorsement? Please read on!

Snail Mail, Rome and Ursula Le Guin

Old fashioned courtesy can go a long way. And so, too, can snail mail. When I requested Ursula Le Guin to endorse my novel I used both.

Last year my first novel, The Wedding Shroud, was published in Australia (and has now been released as an e-book world wide). The book is set in C5th BCE at a time when Rome was still scrapping for ascendancy over its Latin neighbours. The book compares the intolerant insular Romans with its enemies, the Etruscans, a people whose highly sophisticated civilisation spread throughout Italy and across the Mediterranean into northern Europe. My protagonist is a young Roman girl married to an Etruscan nobleman to seal a truce. Leaving behind a righteous society, she is determined to remain true to Roman virtues while living among the sinful Etruscans. Instead she finds herself tempted by a mystical, hedonistic culture which offers pleasure and independence to women.

As an unknown writer I faced the daunting task of gaining publicity and credibility amid a plethora of new releases in the market place. My publisher suggested I have the book endorsed by a well known author. Sounded like a great idea. Only problem was to find one who would do it!

My immediate thought was to find an historical fiction author whom I admired. There was no lack of these. I also thought it would be best if I could identify someone who was interested in the subject matter of my novel not just in history per se.

Around this time, a friend of mine mentioned that Ursula Le Guin’s Lavinia had been released to rave reviews. I was fascinated by this as I only knew her as the eminent author of amazing fantasy novels. I was also intrigued by the title of her book as I recognised it as the name of the wife of Aeneas, the hero of The Aeneid, an epic written by the Roman poet Vergil.

I read Lavinia and was transported back to a time when Rome was yet to be founded and a war weary Trojan wanderer fell in love with the daughter of Latium’s king. The character of Lavinia is not developed in The Aeneid but Ursula Le Guin created a complex woman whose love for a stranger started a war.

As a school girl I loved translating The Aeneid and it struck me that Ursula Le Guin must have a similar affection. In her Author’s Note I read how she had visited the area in Italy where ancient Latium was situated. Her delight in walking the same land upon which her characters had dwelt was clear. Her enthusiasm resonated with me. I also had dreams of standing in the ruins of Veii, the Etruscan city in which my novel is set.

I looked at Ursula Le Guin’s website and found that she was prepared to write blurbs for books but would only respond to letters i.e. snail mail. With a gentle sense of humour she also specified that overseas correspondents should include an international reply coupon if they expected a response due to the fact she would have to bear the costs of mailing a reply. As she personally answered her own correspondence this could take some time. In her own words ‘Silence means I'm sorry: Art is long, life is short, and I want to get on with my own book.’

On the premise of ‘she can only say no’ or more to the point - reply with silence, I wrote her a letter. In it I explained how much I enjoyed Lavinia because of my fondness for Vergil’s The Aeneid. I also provided a one page synopsis of my novel and explained how I, too, wished to walk upon ancient land in reality as well as in my imagination.

I have a vivid memory of hurrying to my local post office and asking for an international reply coupon before slipping the letter into the big red mailbox and crossing my fingers. To my utter astonishment, she responded only a few weeks later to say that she had always been fascinated by the Etruscans and would like to visit ancient Veii through reading my book. Imagine my excitement when she then agreed to endorse it! I still find it hard to believe she was gracious enough to reply let alone write a blurb.

Only Ursula Le Guin can tell why she was prepared to give her time and endorsement to an unknown Australian writer but in the end I believe that, in this world of Twitter, Facebook and email, the old fashioned courtesy of taking time to write and post a letter with a self addressed envelope and a reply coupon must have helped. It was also fate, too, because not longer after this Australia Post phased out international reply coupons. So maybe the Etruscan gods were smiling upon me. I’m certainly glad they did.

~Elisabeth Storrs

Elisabeth Storrs graduated from the University of Sydney in Arts Law, majoring in English and having studied Classics. She lives with her husband and two sons in Sydney and over the years has worked as a solicitor, corporate lawyer, senior manager and company secretary.

Elisabeth's first novel, The Wedding Shroud, is set in early Rome and Etruria, and was researched and written over a period of ten years. It is now available as an ebook world wide. She is currently writing the sequel which will be released by Pier 9 / Murdoch Books in 2012.

Monday, August 15, 2011

Guest post from Nancy Means Wright: An 18th-century Feminist Takes on an Unfair, Feudal Practice

Today author Nancy Means Wright is visiting the blog to discuss the historical practice of primogeniture -- in particular as it figured in the lives of her heroine Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary's contemporaries, and their fictional creations. If you read novels with historical British settings, you'll want to understand the concepts of inheritance law explained in this informative post!

------

An 18th-century Feminist Takes on an Unfair, Feudal Practice

by Nancy Means Wright

“Property, ” Mary Wollstonecraft wrote in her flaming Vindication of the Rights of Man (1790), “should be fluctuating, which would be the case if it were more equally divided amongst all the children of a family. Else it is an everlasting rampart, in consequence of a barbarous feudal institution that enables the elder son to overpower talents and depress virtue.”

The “feudal institution” Mary decried in her rebuttal to the reactionary Edmund Burke, was the law of primogeniture. In practice since the Norman conquest, a father’s fortune would go directly to the eldest son, and so on down the male line—the objective being to keep estates intact from generation to generation.

“Security of property: Behold in a few words, the definition of English ‘liberty,’” was Mary’s ironic reply to Burke, who not only upheld the practice but had attacked Mary’s mentor, Unitarian Dr. Richard Price who like Mary, was thrilled with the Liberté, Égalité ideals of the French Revolutionaries.

“To this selfish principle (primogeniture),” she declared, “every nobler one is sacrificed!”

The practice was ensured by means of entail, a legal arrangement under which the father had only an allowance and life interest in the estate, which was then entailed to the eldest son. Any sale of the property was prevented by law, resulting in vast estates owned by extravagantly rich families. By the mid-19th century, one quarter of all British land was held by a mere 701 individuals. Primogeniture, they insisted, was the only way to ensure political and economic stability, and so remained on the law books until 1925!

Mary’s grandfather had amassed a small fortune as master silk weaver, but her father squandered it in his attempt to become a gentleman farmer. He failed at every move, and drank away much of the inheritance. Mary’s autocratic brother Ned didn’t inherit enough money to became a man of leisure, like many elder brothers, but he did practice law, and kept for himself the small legacy assigned to his six siblings. So after her mother’s death, elder daughter Mary was left with no money, but all the responsibility for her younger brothers and sisters.

At fourteen, Mary’s brother Henry was apprenticed to an apothecary-surgeon, and then disappeared from record. But Mary outfitted James for a naval career, and sent Charles off to make his fortune in America (with middling success). She helped her sister Eliza escape an abusive husband; yet unable to remarry, Eliza had to earn her way as governess. Governessing was the fate of the youngest sister, Everina, as well, and for a time, of Mary herself—“a most humilating occupation!” Her whole short life, Mary sent the little money she earned from her writing to prop up her siblings, along with her feckless father.

No wonder then, that early on, as Virginia Woolf put it, life for Mary became “one cry for justice!” And justice was sorely needed, according to philosopher Francis Bacon, who wrote that tempted by money and power, elder sons were likely to become “disobedient, negligent and wasteful.”

Like Mary, 18th-century Nelly Weeton valued family ties and responsibilities, even rejecting an offer of marriage to keep house for her elder brother Tom after their father died at sea. But Tom, who as a boy was close to Nelly, married a woman who wanted no part of the sister. He ultimately stole the little legacy their mother left Nelly, and virtually sold her into servitude. A desperate marriage to a tyrant who appropriated her teaching money, and after a separation, denied her entry to their daughter, turned Nelly’s life to abject misery. Mary Wollstonecraft’s stepsister, Claire Clairmont, had a similar loss when her indifferent lover, poet Lord Byron, an only son, refused all visits to their daughter, who at eight years of age died alone in a convent.

Although loving and supportive, Jane Austen’s elder brother Edward took advantage of the system through the practice of surrogate heirship and its device of name changing, aimed at keeping estates whole. Edward was adopted by a distant cousin, Thomas Knight, and gave up the name of Austen for Knight when he inherited. Biographer David Nokes suggested that Jane felt abandoned by her brother, although Jane’s only known comment was: “I must learn to make a better K.”

Yet the poison of primogeniture is paramount in Austen’s novels. In Pride and Prejudice the Bennet estate is entailed to the pompous Mr. Collins, clergyman cousin to Mr. Bennet who had no sons, leaving the silly Mrs. Bennet, who finds the subject of entail “beyond the reach of reason,” to scheme up husbands for her five daughters. Should she fail in the event of her husband’s death, mother and daughters would have no home or income. In Northanger Abbey, Austen portrays elder brother Frederick as corrupt and cruel, while in Mansfield Park elder Tom is everyone’s party boy. Austen questions the validity of primogeniture when she makes younger brother Edmund the good son, although the latter loses the young woman he loves because he isn’t rich enough and is destined to become a boring (to her) clergyman. Happily, in the long run, he discovers he’s better off without her.

The disparity of riches between elder and younger brothers was huge, often creating a wide rift between siblings. In a lecture on Shakespeare’s King Lear, Samuel Coleridge notes “the mournful alienation of brotherly love…in children of the same stock.” 19th century Anthony Trollope’s novels are full of younger sons pursuing heiresses, or simply seeking a comfortable bachelorhood without an expensive wife—whereas the elder son must marry in order to produce an heir—think Henry the Eighth!

But considering the fates of Henry’s wives, it was females who were the true victims. For most females there was little money or opportunity to find a suitable husband; some indigent ladies found a taboo against marrying beneath them and remained spinsters. But the main drawback, as Mary Wollstonecraft makes clear in her A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, was failure to receive an equal education. A lack of proper schooling, she allowed, often contributed to a pampered indolence in females, and “a false regard for wealth and status over reason and true moral values.” In her own life, her mother indulged her first born son, neglecting Mary, though it was Mary, not Ned, who lay nights in front of her mother’s bedchamber to waylay the drunken husband.

No doubt Mary was, in part, vindicating the abuses of her own life in her rebuttal to conservative Edmund Burke who considered primogeniture an anchor of social order, but she had known the “demon of property…to encroach on the sacred rights” of legions of unhappy men and women.

“I glow,” she cried, “with indignation!”

------

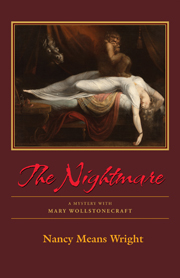

Nancy Means Wright’s latest novel is The Nightmare: a Mystery with Mary Wollstonecraft (Perseverance Press, September, '11). www.nancymeanswright.com

------

An 18th-century Feminist Takes on an Unfair, Feudal Practice

by Nancy Means Wright

“Property, ” Mary Wollstonecraft wrote in her flaming Vindication of the Rights of Man (1790), “should be fluctuating, which would be the case if it were more equally divided amongst all the children of a family. Else it is an everlasting rampart, in consequence of a barbarous feudal institution that enables the elder son to overpower talents and depress virtue.”

The “feudal institution” Mary decried in her rebuttal to the reactionary Edmund Burke, was the law of primogeniture. In practice since the Norman conquest, a father’s fortune would go directly to the eldest son, and so on down the male line—the objective being to keep estates intact from generation to generation.

“Security of property: Behold in a few words, the definition of English ‘liberty,’” was Mary’s ironic reply to Burke, who not only upheld the practice but had attacked Mary’s mentor, Unitarian Dr. Richard Price who like Mary, was thrilled with the Liberté, Égalité ideals of the French Revolutionaries.

“To this selfish principle (primogeniture),” she declared, “every nobler one is sacrificed!”

The practice was ensured by means of entail, a legal arrangement under which the father had only an allowance and life interest in the estate, which was then entailed to the eldest son. Any sale of the property was prevented by law, resulting in vast estates owned by extravagantly rich families. By the mid-19th century, one quarter of all British land was held by a mere 701 individuals. Primogeniture, they insisted, was the only way to ensure political and economic stability, and so remained on the law books until 1925!

Mary’s grandfather had amassed a small fortune as master silk weaver, but her father squandered it in his attempt to become a gentleman farmer. He failed at every move, and drank away much of the inheritance. Mary’s autocratic brother Ned didn’t inherit enough money to became a man of leisure, like many elder brothers, but he did practice law, and kept for himself the small legacy assigned to his six siblings. So after her mother’s death, elder daughter Mary was left with no money, but all the responsibility for her younger brothers and sisters.

At fourteen, Mary’s brother Henry was apprenticed to an apothecary-surgeon, and then disappeared from record. But Mary outfitted James for a naval career, and sent Charles off to make his fortune in America (with middling success). She helped her sister Eliza escape an abusive husband; yet unable to remarry, Eliza had to earn her way as governess. Governessing was the fate of the youngest sister, Everina, as well, and for a time, of Mary herself—“a most humilating occupation!” Her whole short life, Mary sent the little money she earned from her writing to prop up her siblings, along with her feckless father.

No wonder then, that early on, as Virginia Woolf put it, life for Mary became “one cry for justice!” And justice was sorely needed, according to philosopher Francis Bacon, who wrote that tempted by money and power, elder sons were likely to become “disobedient, negligent and wasteful.”

Like Mary, 18th-century Nelly Weeton valued family ties and responsibilities, even rejecting an offer of marriage to keep house for her elder brother Tom after their father died at sea. But Tom, who as a boy was close to Nelly, married a woman who wanted no part of the sister. He ultimately stole the little legacy their mother left Nelly, and virtually sold her into servitude. A desperate marriage to a tyrant who appropriated her teaching money, and after a separation, denied her entry to their daughter, turned Nelly’s life to abject misery. Mary Wollstonecraft’s stepsister, Claire Clairmont, had a similar loss when her indifferent lover, poet Lord Byron, an only son, refused all visits to their daughter, who at eight years of age died alone in a convent.

Although loving and supportive, Jane Austen’s elder brother Edward took advantage of the system through the practice of surrogate heirship and its device of name changing, aimed at keeping estates whole. Edward was adopted by a distant cousin, Thomas Knight, and gave up the name of Austen for Knight when he inherited. Biographer David Nokes suggested that Jane felt abandoned by her brother, although Jane’s only known comment was: “I must learn to make a better K.”

Yet the poison of primogeniture is paramount in Austen’s novels. In Pride and Prejudice the Bennet estate is entailed to the pompous Mr. Collins, clergyman cousin to Mr. Bennet who had no sons, leaving the silly Mrs. Bennet, who finds the subject of entail “beyond the reach of reason,” to scheme up husbands for her five daughters. Should she fail in the event of her husband’s death, mother and daughters would have no home or income. In Northanger Abbey, Austen portrays elder brother Frederick as corrupt and cruel, while in Mansfield Park elder Tom is everyone’s party boy. Austen questions the validity of primogeniture when she makes younger brother Edmund the good son, although the latter loses the young woman he loves because he isn’t rich enough and is destined to become a boring (to her) clergyman. Happily, in the long run, he discovers he’s better off without her.

The disparity of riches between elder and younger brothers was huge, often creating a wide rift between siblings. In a lecture on Shakespeare’s King Lear, Samuel Coleridge notes “the mournful alienation of brotherly love…in children of the same stock.” 19th century Anthony Trollope’s novels are full of younger sons pursuing heiresses, or simply seeking a comfortable bachelorhood without an expensive wife—whereas the elder son must marry in order to produce an heir—think Henry the Eighth!

But considering the fates of Henry’s wives, it was females who were the true victims. For most females there was little money or opportunity to find a suitable husband; some indigent ladies found a taboo against marrying beneath them and remained spinsters. But the main drawback, as Mary Wollstonecraft makes clear in her A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, was failure to receive an equal education. A lack of proper schooling, she allowed, often contributed to a pampered indolence in females, and “a false regard for wealth and status over reason and true moral values.” In her own life, her mother indulged her first born son, neglecting Mary, though it was Mary, not Ned, who lay nights in front of her mother’s bedchamber to waylay the drunken husband.

No doubt Mary was, in part, vindicating the abuses of her own life in her rebuttal to conservative Edmund Burke who considered primogeniture an anchor of social order, but she had known the “demon of property…to encroach on the sacred rights” of legions of unhappy men and women.

“I glow,” she cried, “with indignation!”

------

Nancy Means Wright’s latest novel is The Nightmare: a Mystery with Mary Wollstonecraft (Perseverance Press, September, '11). www.nancymeanswright.com

Friday, August 12, 2011

Reviews of obscure books: Silk and Stone, by Dinah Dean

It's been well over a year since my last entry in the Reviews of Obscure Books series, so I figured it was about time for a new one. This is my copy of Dinah Dean's Silk and Stone, and when you find a book as obscure as this one is, you don't care that one of its past owners slapped an ugly bookplate on the front cover rather than on the flyleaf. Well, actually that's not true, but I'll deal with it.

Among others, Dean has written six mostly unconnected novels that take place in Waltham Abbey in Essex between the 11th and 19th centuries. Silk and Stone, the 2nd in this unofficial series, is set during the civil wars between King Stephen and Empress Matilda in the 1140s. But while the main characters all end up in the East of England, the novel begins on a pilgrimage far to the east and south.

Norman lady Mabilia de Wix, her 17-year-old daughter Elys, and their maid are in Rome, having traveled there in the company of Mabilia's haughty brother, Templar knight Sir Richard de Hastings. Elys's older brother Matthew has a wound in his foot that refuses to heal, and the women have made pilgrimages to holy places all over England and France in the hopes of curing him. All have failed, and they don't understand why. Novelist Diana Norman would have made a slyly irreverent remark about this over-the-top situation, and indeed I expected one, but here, the novel's gentle humor mingles with sadness. Unless Matthew lives, the family's noble line will die out.

If that's not bad enough, Elys hates the thought of going into a convent. Mabilia has plans to retire to the cloister, seeing it as the safest place during these traumatic times of constant war, and wants to see Elys settled there too. Elys's dowry has already been given to the nuns, so she has no hope for a decent marriage. Elys has other plans, though. An accomplished needlewoman, she thinks she has what it takes to be a professional broiderer.

Aylwin of Winchester, a master mason from a noble Saxon bloodline, sympathizes with Elys's predicament, and they become friends as he, his friend Sir Fulk, and her family wander back to England together. Her quest for independence gains ground in the town of Waltham Abbey; she impresses Father Warmand with her skill, and he hires her to design and sew an elaborate cope, or church vestment.

With her unorthodox choice of career, her refusal to become a nun, her mother's and uncle's disapproval, and Sir Fulk's unwillingness to marry her despite his obvious admiration, Elys has her hands full. Aylwin has feelings for her, but Elys is still blind to his attentions. Matthew's days are numbered, too; only a miracle can cure him. Fortunately, one may be at hand.

This isn't a good book on which to test the 50-page rule. Today's commercial fiction is obliged to grip the reader's attention immediately, but the initial few chapters of this one are slow. Imagine the pacing of a pilgrimage in the Middle Ages, and you'll get an idea of how slow. Things pick up as the plot begins to cohere, happily, and as Elys emerges as the novel's central figure.

Her plight is easy to understand — who would want to be forced into a nunnery? — but she belongs to her time rather than ours. Her romance with Aylwin develops realistically, with the shadow of the Norman Conquest, some seventy years earlier, still lingering in the background. She also doesn't realize how fortunate she is, not until later. Through the depiction of Elys's older sister Judith, who is now called Sister Helen, readers get to see the bitter result of a woman's regret-filled life.

Dean presents a wonderfully detailed tapestry of the English medieval world, presenting the day-to-day occupations and concerns of nobility, craftspeople, and churchmen, although the weave isn't always as fine as it could be. In some scenes, she spoon-feeds information on England's political history; in others, she drops readers into a pile of medieval terminology and lets them sort out what's what. I liked the latter approach. The word "mystery" is used in the sense of "miracle," and to her credit, Dean explores her characters' religious mindsets without making them seem holier-than-thou. Instead, their faith feels like a natural part of their existence, which it was.

In her author's note, placed at the very beginning, Dean writes that many of her characters once lived, and that much of her plot is historically based rather than fictional. Lady Mabilia, Sir Richard, Matthew, and several of the townspeople are among the real ones, all mentioned in a chronicle written forty years later.

Dinah Dean's Silk and Stone was published by Barrie & Jenkins, London, in hardcover in 1990 (382pp). The RomanceWiki page has a complete bibliography of her work. Should you be interested in a copy of this one, there are a couple of reasonably-priced ones on Amazon UK. For now.

Among others, Dean has written six mostly unconnected novels that take place in Waltham Abbey in Essex between the 11th and 19th centuries. Silk and Stone, the 2nd in this unofficial series, is set during the civil wars between King Stephen and Empress Matilda in the 1140s. But while the main characters all end up in the East of England, the novel begins on a pilgrimage far to the east and south.

Norman lady Mabilia de Wix, her 17-year-old daughter Elys, and their maid are in Rome, having traveled there in the company of Mabilia's haughty brother, Templar knight Sir Richard de Hastings. Elys's older brother Matthew has a wound in his foot that refuses to heal, and the women have made pilgrimages to holy places all over England and France in the hopes of curing him. All have failed, and they don't understand why. Novelist Diana Norman would have made a slyly irreverent remark about this over-the-top situation, and indeed I expected one, but here, the novel's gentle humor mingles with sadness. Unless Matthew lives, the family's noble line will die out.

If that's not bad enough, Elys hates the thought of going into a convent. Mabilia has plans to retire to the cloister, seeing it as the safest place during these traumatic times of constant war, and wants to see Elys settled there too. Elys's dowry has already been given to the nuns, so she has no hope for a decent marriage. Elys has other plans, though. An accomplished needlewoman, she thinks she has what it takes to be a professional broiderer.

|

| The legendary tomb of King Harold II, which resides in Waltham and is mentioned in the novel |

With her unorthodox choice of career, her refusal to become a nun, her mother's and uncle's disapproval, and Sir Fulk's unwillingness to marry her despite his obvious admiration, Elys has her hands full. Aylwin has feelings for her, but Elys is still blind to his attentions. Matthew's days are numbered, too; only a miracle can cure him. Fortunately, one may be at hand.

This isn't a good book on which to test the 50-page rule. Today's commercial fiction is obliged to grip the reader's attention immediately, but the initial few chapters of this one are slow. Imagine the pacing of a pilgrimage in the Middle Ages, and you'll get an idea of how slow. Things pick up as the plot begins to cohere, happily, and as Elys emerges as the novel's central figure.

Her plight is easy to understand — who would want to be forced into a nunnery? — but she belongs to her time rather than ours. Her romance with Aylwin develops realistically, with the shadow of the Norman Conquest, some seventy years earlier, still lingering in the background. She also doesn't realize how fortunate she is, not until later. Through the depiction of Elys's older sister Judith, who is now called Sister Helen, readers get to see the bitter result of a woman's regret-filled life.

|

| The nave of Waltham Abbey |

In her author's note, placed at the very beginning, Dean writes that many of her characters once lived, and that much of her plot is historically based rather than fictional. Lady Mabilia, Sir Richard, Matthew, and several of the townspeople are among the real ones, all mentioned in a chronicle written forty years later.

Dinah Dean's Silk and Stone was published by Barrie & Jenkins, London, in hardcover in 1990 (382pp). The RomanceWiki page has a complete bibliography of her work. Should you be interested in a copy of this one, there are a couple of reasonably-priced ones on Amazon UK. For now.

Tuesday, August 09, 2011

Book review: The Last Time I Saw Paris, by Lynn Sheene

Lynn Sheene takes risks with her heroine, Claire Harris Stone, by making her a gold-digging Manhattan socialite. In May 1940, with the world on the brink of war, she shamelessly flirts with her husband's German clients to soften them up for business deals. Over the course of her debut novel The Last Time I Saw Paris, Sheene successfully transforms Claire into a woman who's much more selfless and sympathetic, but just as courageous and hard-edged - thanks to the considerable risks Claire takes for herself.

When her husband discovers she's not the blue-blood she claimed to be, Claire flees New York for Paris, the promised City of Light, hoping to connect up with a former lover. Germany has just invaded Poland, but Claire is still taken aback when the Nazis move in to occupy the city. (Her naïveté defies belief at times, especially given her street-smarts in other respects.) She takes refuge with an aristocratic florist, Madame Palain, who employs her under the table. Claire agrees to help the Resistance only because they can provide the fake identity papers she needs.

Madame Palain knows the importance of beauty during hard times and vows to keep her shop open. The floral deliveries Claire makes to Nazi gatherings at swanky hotels gives her the chance to gain intelligence for her contacts, who include an Englishman named Thomas Grey - a friend of her old lover. As she and Grey walk through the Luxembourg Gardens together, exchanging information, their opinions toward one another gradually shift until she comes to care for him and his safety more than she does for herself. Then her cover is blown, for a second time.

The novel offers up a vivid yet stark vision of a cultured European city at one of its darkest hours. Danger is ever-present; people are detained, carted away, and shot for the slimmest of "offenses," and fear and desperation become a tragic part of life. But despite the unease that grips northern France, the indomitable spirit of Paris endures and is described in terms that suit its nature. One park is "a stately woman, her well-bred bones showing through the ravages of the season." The plot grows increasingly suspenseful as the months and years pass under the Occupation, and as Claire is exposed to greater peril.

The ending raises more questions than it answers, but The Last Time I Saw Paris is well worth reading for its page-turning storyline, edgy atmosphere, and progressive insight into the character of a determined woman with a strong instinct for survival.

The Last Time I Saw Paris appeared in May from Berkley at $15/$17.50 in Canada (trade paperback, 354pp).

When her husband discovers she's not the blue-blood she claimed to be, Claire flees New York for Paris, the promised City of Light, hoping to connect up with a former lover. Germany has just invaded Poland, but Claire is still taken aback when the Nazis move in to occupy the city. (Her naïveté defies belief at times, especially given her street-smarts in other respects.) She takes refuge with an aristocratic florist, Madame Palain, who employs her under the table. Claire agrees to help the Resistance only because they can provide the fake identity papers she needs.

Madame Palain knows the importance of beauty during hard times and vows to keep her shop open. The floral deliveries Claire makes to Nazi gatherings at swanky hotels gives her the chance to gain intelligence for her contacts, who include an Englishman named Thomas Grey - a friend of her old lover. As she and Grey walk through the Luxembourg Gardens together, exchanging information, their opinions toward one another gradually shift until she comes to care for him and his safety more than she does for herself. Then her cover is blown, for a second time.

The novel offers up a vivid yet stark vision of a cultured European city at one of its darkest hours. Danger is ever-present; people are detained, carted away, and shot for the slimmest of "offenses," and fear and desperation become a tragic part of life. But despite the unease that grips northern France, the indomitable spirit of Paris endures and is described in terms that suit its nature. One park is "a stately woman, her well-bred bones showing through the ravages of the season." The plot grows increasingly suspenseful as the months and years pass under the Occupation, and as Claire is exposed to greater peril.

The ending raises more questions than it answers, but The Last Time I Saw Paris is well worth reading for its page-turning storyline, edgy atmosphere, and progressive insight into the character of a determined woman with a strong instinct for survival.

The Last Time I Saw Paris appeared in May from Berkley at $15/$17.50 in Canada (trade paperback, 354pp).

Saturday, August 06, 2011

Book review: Before Ever After, by Samantha Sotto

Get ready for the unexpected when you pick up this offbeat, incredibly enjoyable novel, which will transport you on a memorable journey through Europe old and new.

American expat Shelley Gallus had put her life on hold after her husband, Max, was killed in a Madrid train bombing three years earlier. When a man who is his spitting image rings her doorbell in London, claiming to be Max’s grandson, Paolo, Shelley refuses to believe this time-bending impossibility. That is, until the similarities between Max and Paolo’s beloved and seemingly ageless "Nonno" become too profound to ignore.

She and Paolo board a plane for the Philippines, where he believes Max has resurfaced. Shelley’s reminiscences about how she and Max first met form the heart of the novel, and although its structure jumps around a lot, the story is easy to follow. Max had been her guide on a laid-back package tour through the back roads of Europe that Shelley joined on impulse.

As the tour group’s VW van rumbles along from the steps of Montmartre to Switzerland’s Emmental Valley, and from the red-roofed skyline of Slovenia's capital to the shadow of Mt. Vesuvius, Max recounts folkloric vignettes from history, each one set further back in time. Each is a perfect little slice of the past featuring ordinary people, their difficult times, and how they fought to save their loved ones.

Back on the plane with Paolo, Shelley realizes that perhaps Max’s stories were more than that. Perhaps they were his way of telling the truth about himself.

Sotto’s deceptively slim debut is as rich and satisfying as one of Max's famous baked egg and cheese breakfasts, minus the calories and cholesterol. Its tone moves from zany to thoughtful to painfully sad and back again, all the while evoking the lengths people travel for love.

Before Ever After was published by Crown in August at $23.00/$25.95 in Canada (hardcover, 294pp). Stop on over to the author's website for back story, her blog, a virtual tour of the places in the book, and pics of the cutest little VW van. This review was first published in August's Historical Novels Review.

American expat Shelley Gallus had put her life on hold after her husband, Max, was killed in a Madrid train bombing three years earlier. When a man who is his spitting image rings her doorbell in London, claiming to be Max’s grandson, Paolo, Shelley refuses to believe this time-bending impossibility. That is, until the similarities between Max and Paolo’s beloved and seemingly ageless "Nonno" become too profound to ignore.

She and Paolo board a plane for the Philippines, where he believes Max has resurfaced. Shelley’s reminiscences about how she and Max first met form the heart of the novel, and although its structure jumps around a lot, the story is easy to follow. Max had been her guide on a laid-back package tour through the back roads of Europe that Shelley joined on impulse.

As the tour group’s VW van rumbles along from the steps of Montmartre to Switzerland’s Emmental Valley, and from the red-roofed skyline of Slovenia's capital to the shadow of Mt. Vesuvius, Max recounts folkloric vignettes from history, each one set further back in time. Each is a perfect little slice of the past featuring ordinary people, their difficult times, and how they fought to save their loved ones.

Back on the plane with Paolo, Shelley realizes that perhaps Max’s stories were more than that. Perhaps they were his way of telling the truth about himself.

Sotto’s deceptively slim debut is as rich and satisfying as one of Max's famous baked egg and cheese breakfasts, minus the calories and cholesterol. Its tone moves from zany to thoughtful to painfully sad and back again, all the while evoking the lengths people travel for love.

Before Ever After was published by Crown in August at $23.00/$25.95 in Canada (hardcover, 294pp). Stop on over to the author's website for back story, her blog, a virtual tour of the places in the book, and pics of the cutest little VW van. This review was first published in August's Historical Novels Review.

Wednesday, August 03, 2011

An interview with Sonia Gensler, author of The Revenant

You'll find Sonia Gensler's The Revenant shelved in the Teen Paranormal Romance section at your local bookstore. However, it has far more in common with creepy supernatural mysteries like Patricia Clapp's Jane-Emily and Sarah Waters' The Little Stranger than it does with Twilight and its ilk.

The year is 1896, and 17-year old Willemina Hammond is desperate. To escape a home situation she detests, she boards a train from Tennessee to Indian Territory and steals the identity of one of her former classmates. But Willie's assumed role as an English teacher at the Cherokee Female Seminary in Tahlequah, Oklahoma is nothing like she expects.

Willie struggles to gain authority over her cliquish pupils, who are the same age as she is, and whose upper-class background gives them a sophistication she herself doesn't have. Then Willie learns that her bedroom used to belong to a former student who drowned in the river last year. What's causing the tapping on her window after dark — is it poor Ella's ghost, and if so, what does Ella want to tell her? What ever happened to the boy rumored to be Ella's lover? And can a romance between Willie and Eli Sevenstar, a handsome older student at the male seminary across town, ever work out?

Willie struggles to gain authority over her cliquish pupils, who are the same age as she is, and whose upper-class background gives them a sophistication she herself doesn't have. Then Willie learns that her bedroom used to belong to a former student who drowned in the river last year. What's causing the tapping on her window after dark — is it poor Ella's ghost, and if so, what does Ella want to tell her? What ever happened to the boy rumored to be Ella's lover? And can a romance between Willie and Eli Sevenstar, a handsome older student at the male seminary across town, ever work out?

The Cherokee Female Seminary was a real place, an institution of higher learning for wealthy Cherokee girls and lower-class scholarship students. Its building — a three-story, turreted structure that resembles a castle — is now part of the Northeastern State University campus. I loved walking through the rooms of the seminary along with Willie, noting the fully stocked library and gleaming wood tables and chairs. Willie's awkward experiences in front of a classroom ring true, the depiction of late 19th-century Cherokee life is seen from an intriguing new perspective, and the ghost story is eerie and unpredictable. The Revenant is an engrossing read which should appeal equally well to adults and YAs.

I hope you'll enjoy the following interview!

I wasn't familiar with the term "revenant" before picking up your book. What's the difference between a revenant and a regular ghost, if there is such a thing?

I don’t think there really is a difference. Revenant, with its French origins, seemed a more old-fashioned and romantic word to me than ghost, and over the course of the story I was able to give a double meaning to its definition of “one who returns.” I think the term can include creatures such as vampires or zombies, but obviously I didn’t go in that direction for this story!

How do you get into the right mood for writing scary scenes, like the ones in which Willie hears mysterious tapping at her window very late at night?

No one has asked this question before! Actually, it’s sort of the same as when I write romantic scenes. I rarely try to “set the mood” – I don’t have to be scared in order to write a scary scene. At times I try to remember moments when I was scared, but I have to be thinking pretty calmly and objectively in order to write about those moments. When the scene is stubbornly refusing to flow, I might review scary scenes from favorite ghostly novels for inspiration.

Now that I see how mundane my answer is, I’m tempted to light candles and play spooky music next time I have to write a scary scene, just to see how that affects the process!

I found your depiction of the Cherokee students and their families fascinating and enlightening, because it's a chapter of their history - and a segment of the population - you don't often read about. What sort of research did you do to ensure that the Cherokee characters were portrayed correctly?

For my research I visited the Oklahoma Historical Society and the Northeastern State University Archives. I also had the benefit of reading Devon Mihesuah’s Cultivating the Rosebuds: The Education of Women at the Cherokee Female Seminary, 1851-1909 as well a collection of oral histories entitled Cherokee Female Seminary Years, edited by Maggie Culver Fry. These books, along with the photographs, school catalogs, architectural plans, etc. obtained through the archives, gave me a pretty clear background on the history of the town, seminaries, and people. Once I had a draft, I arranged for an introduction to Dr. Richard Allen, former English teacher and current policy analyst for the Cherokee Nation. He kindly agreed to read the manuscript for me and offered valuable insights on historical context and characterization.

What sorts of things did you discover while doing on-site exploration of the old seminary building that you wouldn't have known about otherwise?

I think it was during a tour that I learned what parts of the building were off-limits to male seminary students. When invited to the school, boys were allowed access to the first floor, but could only step as far as the first landing on the staircase to the second floor. They were NOT to go to near the girls’ bedrooms. This wasn’t surprising information by any means, but it did get me thinking about certain plot points . . .

I know it may not be fair to ask a teacher to choose a favorite student, but were there any of the girls (or boys) whose backstory or character you enjoyed developing the most?

Fannie and Larkin Bell weren’t necessarily my favorite characters, but I did enjoy fleshing them out as the “mean girl” and her rakish older brother. It was especially fun to imagine their home for the Christmas party scenes – the house was loosely based on Rose Cottage in Park Hill, the home of Chief John Ross. Fannie is a royal pain, but I tried to show her strengths as well as flaws. I like to imagine that her frightening experiences at the seminary tempered her vanity and snobbery.

Willie's enthusiasm for Shakespeare's plays comes through clearly to her students at the Cherokee Female Seminary. Back when you were a teacher, did you have any favorite Shakespeare plays to read and act out with your classes?

I required my English II students to act out the assassination scene from Julius Caesar every year. They usually had a great time with that. It was a complicated and often maddening effort to throw costumes and props together and, after much rehearsing, film the scene. The experience certainly made for a great discussion when the students compared their version to the same scene in the 1970 film adaptation of the play, which portrays the assassination very . . . vividly.

Were there any fascinating tidbits you picked up during the writing process that you wanted to use in The Revenant but were unable to?

During the research process I went on one of the Haunted Seminary Hall tours, which are offered every October by Northeastern State University graduate students. At one point the guide took us to the second floor and, after pushing aside a tile from the drop ceiling, showed us what certainly looked like footprints on the original plaster ceiling. It was quite eerie, and no one had an explanation for it. I wish I could have worked that into the story somehow, but the proper way to include it never came to me.

Although Willie's only seventeen, the role she assumes puts her in an unusual position - she's expected to associate with other adults rather than students of her own age. For this and other reasons, I could easily see your book appealing to both YAs and adults. Did you deliberately set out to write a novel for the YA market, or didn't you have an age group in mind?

I did set out to write The Revenant as a YA book, but with the knowledge that YA has considerable crossover appeal to the adult market these days. The teen years are inherently full of drama and conflict, and I feel that most adults still have vivid memories of that time in their lives. I also liked the idea of my protagonist putting on a performance, and in this case, she was pretending to be an adult – a common fantasy for teens.

Thank you, Sonia!

------

The Revenant was published in June by Knopf in hardback ($16.99/$18.99 Canadian, 322pp). Visit Sonia's website at www.soniagensler.com for biographical information plus more historical background on the novel.

The year is 1896, and 17-year old Willemina Hammond is desperate. To escape a home situation she detests, she boards a train from Tennessee to Indian Territory and steals the identity of one of her former classmates. But Willie's assumed role as an English teacher at the Cherokee Female Seminary in Tahlequah, Oklahoma is nothing like she expects.

Willie struggles to gain authority over her cliquish pupils, who are the same age as she is, and whose upper-class background gives them a sophistication she herself doesn't have. Then Willie learns that her bedroom used to belong to a former student who drowned in the river last year. What's causing the tapping on her window after dark — is it poor Ella's ghost, and if so, what does Ella want to tell her? What ever happened to the boy rumored to be Ella's lover? And can a romance between Willie and Eli Sevenstar, a handsome older student at the male seminary across town, ever work out?

Willie struggles to gain authority over her cliquish pupils, who are the same age as she is, and whose upper-class background gives them a sophistication she herself doesn't have. Then Willie learns that her bedroom used to belong to a former student who drowned in the river last year. What's causing the tapping on her window after dark — is it poor Ella's ghost, and if so, what does Ella want to tell her? What ever happened to the boy rumored to be Ella's lover? And can a romance between Willie and Eli Sevenstar, a handsome older student at the male seminary across town, ever work out?The Cherokee Female Seminary was a real place, an institution of higher learning for wealthy Cherokee girls and lower-class scholarship students. Its building — a three-story, turreted structure that resembles a castle — is now part of the Northeastern State University campus. I loved walking through the rooms of the seminary along with Willie, noting the fully stocked library and gleaming wood tables and chairs. Willie's awkward experiences in front of a classroom ring true, the depiction of late 19th-century Cherokee life is seen from an intriguing new perspective, and the ghost story is eerie and unpredictable. The Revenant is an engrossing read which should appeal equally well to adults and YAs.

I hope you'll enjoy the following interview!

I wasn't familiar with the term "revenant" before picking up your book. What's the difference between a revenant and a regular ghost, if there is such a thing?

I don’t think there really is a difference. Revenant, with its French origins, seemed a more old-fashioned and romantic word to me than ghost, and over the course of the story I was able to give a double meaning to its definition of “one who returns.” I think the term can include creatures such as vampires or zombies, but obviously I didn’t go in that direction for this story!

How do you get into the right mood for writing scary scenes, like the ones in which Willie hears mysterious tapping at her window very late at night?

No one has asked this question before! Actually, it’s sort of the same as when I write romantic scenes. I rarely try to “set the mood” – I don’t have to be scared in order to write a scary scene. At times I try to remember moments when I was scared, but I have to be thinking pretty calmly and objectively in order to write about those moments. When the scene is stubbornly refusing to flow, I might review scary scenes from favorite ghostly novels for inspiration.

Now that I see how mundane my answer is, I’m tempted to light candles and play spooky music next time I have to write a scary scene, just to see how that affects the process!