------

An 18th-century Feminist Takes on an Unfair, Feudal Practice

by Nancy Means Wright

“Property, ” Mary Wollstonecraft wrote in her flaming Vindication of the Rights of Man (1790), “should be fluctuating, which would be the case if it were more equally divided amongst all the children of a family. Else it is an everlasting rampart, in consequence of a barbarous feudal institution that enables the elder son to overpower talents and depress virtue.”

The “feudal institution” Mary decried in her rebuttal to the reactionary Edmund Burke, was the law of primogeniture. In practice since the Norman conquest, a father’s fortune would go directly to the eldest son, and so on down the male line—the objective being to keep estates intact from generation to generation.

“Security of property: Behold in a few words, the definition of English ‘liberty,’” was Mary’s ironic reply to Burke, who not only upheld the practice but had attacked Mary’s mentor, Unitarian Dr. Richard Price who like Mary, was thrilled with the Liberté, Égalité ideals of the French Revolutionaries.

“To this selfish principle (primogeniture),” she declared, “every nobler one is sacrificed!”

The practice was ensured by means of entail, a legal arrangement under which the father had only an allowance and life interest in the estate, which was then entailed to the eldest son. Any sale of the property was prevented by law, resulting in vast estates owned by extravagantly rich families. By the mid-19th century, one quarter of all British land was held by a mere 701 individuals. Primogeniture, they insisted, was the only way to ensure political and economic stability, and so remained on the law books until 1925!

Mary’s grandfather had amassed a small fortune as master silk weaver, but her father squandered it in his attempt to become a gentleman farmer. He failed at every move, and drank away much of the inheritance. Mary’s autocratic brother Ned didn’t inherit enough money to became a man of leisure, like many elder brothers, but he did practice law, and kept for himself the small legacy assigned to his six siblings. So after her mother’s death, elder daughter Mary was left with no money, but all the responsibility for her younger brothers and sisters.

At fourteen, Mary’s brother Henry was apprenticed to an apothecary-surgeon, and then disappeared from record. But Mary outfitted James for a naval career, and sent Charles off to make his fortune in America (with middling success). She helped her sister Eliza escape an abusive husband; yet unable to remarry, Eliza had to earn her way as governess. Governessing was the fate of the youngest sister, Everina, as well, and for a time, of Mary herself—“a most humilating occupation!” Her whole short life, Mary sent the little money she earned from her writing to prop up her siblings, along with her feckless father.

No wonder then, that early on, as Virginia Woolf put it, life for Mary became “one cry for justice!” And justice was sorely needed, according to philosopher Francis Bacon, who wrote that tempted by money and power, elder sons were likely to become “disobedient, negligent and wasteful.”

Like Mary, 18th-century Nelly Weeton valued family ties and responsibilities, even rejecting an offer of marriage to keep house for her elder brother Tom after their father died at sea. But Tom, who as a boy was close to Nelly, married a woman who wanted no part of the sister. He ultimately stole the little legacy their mother left Nelly, and virtually sold her into servitude. A desperate marriage to a tyrant who appropriated her teaching money, and after a separation, denied her entry to their daughter, turned Nelly’s life to abject misery. Mary Wollstonecraft’s stepsister, Claire Clairmont, had a similar loss when her indifferent lover, poet Lord Byron, an only son, refused all visits to their daughter, who at eight years of age died alone in a convent.

Although loving and supportive, Jane Austen’s elder brother Edward took advantage of the system through the practice of surrogate heirship and its device of name changing, aimed at keeping estates whole. Edward was adopted by a distant cousin, Thomas Knight, and gave up the name of Austen for Knight when he inherited. Biographer David Nokes suggested that Jane felt abandoned by her brother, although Jane’s only known comment was: “I must learn to make a better K.”

Yet the poison of primogeniture is paramount in Austen’s novels. In Pride and Prejudice the Bennet estate is entailed to the pompous Mr. Collins, clergyman cousin to Mr. Bennet who had no sons, leaving the silly Mrs. Bennet, who finds the subject of entail “beyond the reach of reason,” to scheme up husbands for her five daughters. Should she fail in the event of her husband’s death, mother and daughters would have no home or income. In Northanger Abbey, Austen portrays elder brother Frederick as corrupt and cruel, while in Mansfield Park elder Tom is everyone’s party boy. Austen questions the validity of primogeniture when she makes younger brother Edmund the good son, although the latter loses the young woman he loves because he isn’t rich enough and is destined to become a boring (to her) clergyman. Happily, in the long run, he discovers he’s better off without her.

The disparity of riches between elder and younger brothers was huge, often creating a wide rift between siblings. In a lecture on Shakespeare’s King Lear, Samuel Coleridge notes “the mournful alienation of brotherly love…in children of the same stock.” 19th century Anthony Trollope’s novels are full of younger sons pursuing heiresses, or simply seeking a comfortable bachelorhood without an expensive wife—whereas the elder son must marry in order to produce an heir—think Henry the Eighth!

But considering the fates of Henry’s wives, it was females who were the true victims. For most females there was little money or opportunity to find a suitable husband; some indigent ladies found a taboo against marrying beneath them and remained spinsters. But the main drawback, as Mary Wollstonecraft makes clear in her A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, was failure to receive an equal education. A lack of proper schooling, she allowed, often contributed to a pampered indolence in females, and “a false regard for wealth and status over reason and true moral values.” In her own life, her mother indulged her first born son, neglecting Mary, though it was Mary, not Ned, who lay nights in front of her mother’s bedchamber to waylay the drunken husband.

No doubt Mary was, in part, vindicating the abuses of her own life in her rebuttal to conservative Edmund Burke who considered primogeniture an anchor of social order, but she had known the “demon of property…to encroach on the sacred rights” of legions of unhappy men and women.

“I glow,” she cried, “with indignation!”

------

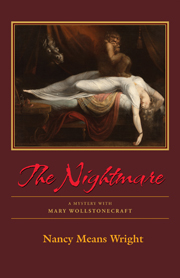

Nancy Means Wright’s latest novel is The Nightmare: a Mystery with Mary Wollstonecraft (Perseverance Press, September, '11). www.nancymeanswright.com

Mary Wollstonecraft’s stepsister, Claire Clairmont ... no.

ReplyDeleteClaire Clairmont Mary Godwin Shelley's tepsister -- Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin was Mary Godwin's mother, who died early in the girl's life.

Love, C.

I do not know what is going on with the internets these days, with the constant dropping of letters and words phrases from between proofing and submitting.

ReplyDeleteThat was supposed to be:

"Claire Clairmont was Mary Godwin Shelley's stepsister -- because Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin was Mary Godwin's mother, who died early in the girl's life, leaving William Godwin free to re-marry Claire's mother."

Love, C.

Ah, my embarrassing error, Foxessa. I know, of course, it was Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley's stepsister.I've read five biographies! I dumbly left off the last two names. Thanks for catching me up on this! (Nancy)

ReplyDeleteThank you for this informative post Nancy. I enjoyed reading it.

ReplyDeleteThanks for you kind comment, Phastings! And thanks to historian Sarah Johnson for offering me post-time on her wonderful site. So much to learn from everyone here!

ReplyDeleteEvery book on women should have info on their legal/political status. Otherwise it's a very incomplete picture.

ReplyDeleteNancy, maybe you can explain something I've always wondered about (re your mention of Pride & Prejudice): if the Bennet estate is entailed to the male line, and cousin Collins is the heir, why is he a Collins instead of a Bennet? Did someone back in his family tree change his name as you mentioned (first time I'd heard of that practice)? Because otherwise he'd be related to Mr Bennet through his mom or grandma Bennet who married a Collins (presumably), and would therefore be unable to inherit via the entail. Ah, the details that keep you up at night.

ReplyDeleteIf I recall the law of entail correctly, an entail could only be broken if the second (and third?) generation consented to break it--that is, everyone had to consent at once. Usually that didn't happen, but it was legally possible. Estates could also, rarely, be entailed on the female line.

ReplyDeleteYounger sons were generally expected to enter the Church, the Army (military), or the Law. In theory, this would provide them with the means of living. However, if the oldest brother failed to honor his responsibilities, and no independent legacy was willed to other siblings, then yes, the system had room for considerable abuses, including the ones you've mentioned.

Thanks for a really interesting post!

@ Suzanne

ReplyDeleteHere's a link that offers a possible explanation. :)

http://austenacious.com/?p=2198

I meant Susanne--sorry, misspelled your name.

ReplyDeleteI agree with you, Shelley. We need that information to have an honest, in-depth portrait of a woman--historical or modern. Have you seen many books on women that don't refer to their legal / political status? Or some that do and that you've enjoyed reading?

ReplyDeleteFascinating post. I'm definitely going to look for Wright's novel!

ReplyDeleteProvocative question re: the name difference, Susanne--and I'll check on the link you mention, Lucy--thanks for that! I don't recall Austen giving an explanation, but it could well be as you suggest, the name change that happened to Austen's brother--one reason for Austen giving a different name in P&P. Surely Mr Bennet was cruel in announcing the takeover by his cousin, Mr Collins, who, "when I am dead, may turn you all out of this house, as soon as he pleases."

ReplyDeleteThanks for your comment, Audra. What a great portrait by your post! I'd love to see a close-up.

ReplyDeleteHello, all: I just checked on Lucy's link (thanks again, Lucy), which concludes that one of Mr Collins's male ancestors must have changed his name (which happened 3 times in Austen's family), or adopted a boy for this purpose. OR, for convenience, Austen didn't want to have two male characters with the same name!! I'll bet this figured into her thinking.

ReplyDeleteThis is a great conversation - thanks for following up so quickly with everyone's comments, Nancy! It's been a pleasure to have you as a guest author again on the site. The question about Mr Collins should have occurred to me before now. What a convoluted state of affairs for genealogists!

ReplyDeleteI did, in a contemporary mystery, come across a "modern" entail, which apparently still exist here and there in the UK (modern as opposed to entails connected to medieval estates granted with titles of nobility, which still, I guess, technically belong to the Crown).

ReplyDeleteThe only way to break it was if the current owner of the property (who was presumably of age) and also the heir to the property according to the rules of the entail--who also had to be of legal age--both agreed to break it. In the mystery, someone wanted the entail to stay in place (possibly because it would cover some skulduggery, IIRC) and thus tried to murder either the father or the sole (underage) child--it didn't matter which!

The same thing happens in the first season of the BBC / PBS Downton Abbey series: a cousin with a different name who is male is the heir since the current occupant's children are all female. This is the point of the first series.

ReplyDeleteThe second series -- well it's WWI. All the while watching the first season, every young or youngish man that appears, I wondered, will you be alive next year? Or the year after that?

I didn't care a pin for the presumably passed over female -- but her feminist younger sister -- o my! She shall come into her own surely in this second season -- all this by way of saying that here is another who agrees with Shelley's statement!

Love, C.

I can't wait till the next Downton Abbey series comes to North America! BTW,we've been continuing this primogeniture conversation on CrimethruTime, Sarah. More intriguing comments to learn from...

ReplyDeleteHi Nancy, I'm a longtime lurker on CrimeThruTime so have been enjoying the conversation there too! And I really must see Downton Abbey for myself.

ReplyDelete