The lives of trailblazing English proto-feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and her daughter, Frankenstein author Mary Shelley, overlapped by only eleven days, as Wollstonecraft tragically died from postpartum infection in 1797. In her second novel, Silva (Mr. Dickens and His Carol, 2019) probes the perspective of another literary icon, imagining the older Mary, weakened from childbirth, telling her life story to her baby at her midwife’s suggestion.

Mary’s passionate declaration of selfhood carries readers on a wide-ranging, deep journey where she eloquently voices the circumstances shaping her views, her strong attachments to other independent thinkers, like Fanny Blood, and her struggles to escape societal constraints. Raised in a large family where her father abused her mother, she grows infuriated by gender inequality and aims to enlighten women who participate in their own diminution.

Related with superb detail on late-eighteenth-century locales and intellectual pursuits, Mary’s experiences leave her initially doubting the possibility of equal marriage between men and women. This absorbing tale of courage, sorrow, and the dance between independence and intimacy delivers a sense of triumphant catharsis.

Love and Fury was published by Flatiron in May, and I'd turned in this review for Booklist (the final version was published in their historical fiction issue on May 15th). Allison & Busby will publish the novel in the UK in mid-June. Terrific book, with a beautiful cover. You can read an excerpt at the author's website.

Monday, May 31, 2021

Sunday, May 30, 2021

Historical fiction giveaway for Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month

In March, at the time of the blog's 15th anniversary, I'd mentioned I'd be posting a giveaway sometime soon. I decided to offer one during Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month (May), since this gives me the chance to offer up copies of four excellent historical novels, set in different countries within Asia and by writers of Asian heritage. All were five star reads for me.

Here are the books and links to my earlier reviews:

Janie Chang, The Library of Legends, which follows a real and mystical journey through war-torn 1937 China.

Charmaine Craig, Miss Burma, an engrossing novel of family, politics, and the history of modern Burma, based on the lives of the author's mother and grandparents.

Min Jin Lee, Pachinko, the bestselling, critically acclaimed novel of Korean life in 20th-century Japan.

Sujata Massey, The Widows of Malabar Hill, an original mystery (first in a series) starring the only female lawyer in 1920s Bombay.

To enter, fill in the form below. (For email subscribers, please visit the original blog post to enter the giveaway.) Deadline is Sunday, June 6th, a week from today. The winners will be randomly chosen and notified after the deadline. This giveaway is being funded by me, and is open to all readers in countries where Amazon or Book Depository delivers, except where prohibited by local laws.

Good luck!

Tuesday, May 25, 2021

Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead, an adventurous historical fiction epic about daring, unconventional women

Great Circle is a richly spacious novel about a bold female pilot who feels simultaneously larger-than-life and intimately real. Marian Graves leaves behind a logbook from her final flight in 1950, when she attempted to circumnavigate the globe longitudinally. “My last descent won’t be the tumbling helpless kind but a sharp gannet plunge,” she writes, just before disappearing over Antarctica. A fictional character, Marian sits alongside historic aviators like Amy Johnson and Elinor Smith, whose tales are highlighted in asides, but her path is her own.

Marian’s early life is similarly dramatic. As infants in 1914, she and twin brother Jamie are saved from a burning ship and sent to Missoula, Montana, to stay with their uncle, an artist with a gambling problem. Two barnstormer pilots ignite Marian’s urge to expand her world, but flying lessons are costly and inappropriate for girls.

Seeking direction and funding, she forms a reluctant attachment to Barclay McQueen, a wealthy, controlling bootlegger. Jamie, a vegetarian and pacifist, is equally captivating. Like Marian, he enters into relationships that spur him to confront his values.

Their stories run alongside that of Hadley Baxter, a contemporary actress whose messy love life is sabotaging her career. By playing Marian in a new biopic, she hopes to begin anew. Hadley’s account initially feels superficial in comparison, but as she researches her subject, the timelines have an exciting interplay, and missing pieces click into place.

The characters’ journeys encompass many locales – 1920s Montana, wild remote Alaska, WWII England with the Air Transport Auxiliary, a cloud’s opaque, dizzying interior – yet the research feels weightless. The vast black crevasse Marian glimpses while flying over western Canada comes to symbolize life’s darknesses: how do we move past situations that threaten to swallow us whole? Imbued with adventurous spirit and rendered in gorgeous language, this is an epic worth savoring.

Great Circle was published by Knopf this month, and I'd reviewed it for May's Historical Novels Review from a NetGalley copy. If you're not convinced yet to put it on your TBR, read Ron Charles's review at the Washington Post, which recommends it as "perfect summer novel." All of his reviews are terrific and worth reading regardless.

Marian’s early life is similarly dramatic. As infants in 1914, she and twin brother Jamie are saved from a burning ship and sent to Missoula, Montana, to stay with their uncle, an artist with a gambling problem. Two barnstormer pilots ignite Marian’s urge to expand her world, but flying lessons are costly and inappropriate for girls.

Seeking direction and funding, she forms a reluctant attachment to Barclay McQueen, a wealthy, controlling bootlegger. Jamie, a vegetarian and pacifist, is equally captivating. Like Marian, he enters into relationships that spur him to confront his values.

Their stories run alongside that of Hadley Baxter, a contemporary actress whose messy love life is sabotaging her career. By playing Marian in a new biopic, she hopes to begin anew. Hadley’s account initially feels superficial in comparison, but as she researches her subject, the timelines have an exciting interplay, and missing pieces click into place.

The characters’ journeys encompass many locales – 1920s Montana, wild remote Alaska, WWII England with the Air Transport Auxiliary, a cloud’s opaque, dizzying interior – yet the research feels weightless. The vast black crevasse Marian glimpses while flying over western Canada comes to symbolize life’s darknesses: how do we move past situations that threaten to swallow us whole? Imbued with adventurous spirit and rendered in gorgeous language, this is an epic worth savoring.

Great Circle was published by Knopf this month, and I'd reviewed it for May's Historical Novels Review from a NetGalley copy. If you're not convinced yet to put it on your TBR, read Ron Charles's review at the Washington Post, which recommends it as "perfect summer novel." All of his reviews are terrific and worth reading regardless.

Sunday, May 23, 2021

Edward Rutherfurd's China takes an epic, multi-perspective look at 19th-century Chinese history

For his newest epic about an intriguing world locale, Rutherfurd (Paris, 2013) dives into seventy years of Chinese history, beginning in 1839, as circumstances lead to the First Opium War, through the Boxer Rebellion and after.

The novel has a tighter scope, time-wise, than his usual canvas, which allows for in-depth exploration of an overarching theme: China’s subjugation by Western powers, particularly Britain.

Taking the long view, Rutherfurd adeptly dramatizes the impact of and fallout from major events, including the Taiping Rebellion and the destruction of Beijing’s Summer Palace. His characters, among them British merchants, missionaries, Chinese government officials, peasants, pirates, and an artisan who rises high in service at the imperial palace through unusual means, assert their individuality while embodying beliefs on different sides of China’s internal and external conflicts.

The protagonists are predominantly men, but many fascinating women also feature in the story. Though the first third feels overly drawn-out, the novel takes an entertaining, educational journey through China’s rich and complex history, geography, art, and diverse cultures across a tumultuous epoch.

Edward Rutherfurd's China was published by Doubleday this May in the US, and I wrote this review (based on a PDF sent to me) for Booklist. The novel is 800pp long, and these days I find longer books easier to read in electronic form, so the PDF worked just fine. Your mileage may vary, though, and I have most of Rutherfurd's earlier novels in hardcover. My favorite among his work is The Princes of Ireland, the first in his two-book Dublin saga.

The novel has a tighter scope, time-wise, than his usual canvas, which allows for in-depth exploration of an overarching theme: China’s subjugation by Western powers, particularly Britain.

Taking the long view, Rutherfurd adeptly dramatizes the impact of and fallout from major events, including the Taiping Rebellion and the destruction of Beijing’s Summer Palace. His characters, among them British merchants, missionaries, Chinese government officials, peasants, pirates, and an artisan who rises high in service at the imperial palace through unusual means, assert their individuality while embodying beliefs on different sides of China’s internal and external conflicts.

The protagonists are predominantly men, but many fascinating women also feature in the story. Though the first third feels overly drawn-out, the novel takes an entertaining, educational journey through China’s rich and complex history, geography, art, and diverse cultures across a tumultuous epoch.

Edward Rutherfurd's China was published by Doubleday this May in the US, and I wrote this review (based on a PDF sent to me) for Booklist. The novel is 800pp long, and these days I find longer books easier to read in electronic form, so the PDF worked just fine. Your mileage may vary, though, and I have most of Rutherfurd's earlier novels in hardcover. My favorite among his work is The Princes of Ireland, the first in his two-book Dublin saga.

Saturday, May 22, 2021

A note for email subscribers to Reading the Past: mailing list migration next weekend

On April 14, I got an email from Google letting me know that its FeedBurner email subscription feature would be discontinued in July. FeedBurner is the application that powers the "Subscribe by email" widget used by Blogger, which I've been using for the past dozen years.

Software changes can be annoying, but free technology services don't last forever, and I'm glad FeedBurner has been up and running reliably for so long.

Since I got the news about the change, I've been looking for another product so that readers could receive new blog posts via email, and finally settled on Mailchimp.

I plan to migrate the list of email subscribers to the new Mailchimp platform over Memorial Day weekend in the US (May 29-31). If you're currently subscribed via email, you'll continue to be subscribed after the move. I expect everything will go smoothly (fingers crossed!).

The new emails will be coming from my address rather than from Google.com, so if you're a subscriber, you may want to add my email (sarah at readingthepast dot com) to your approved senders list so you don't miss anything.

Anyone who signed up for email updates within the last two weeks is already on the new mailing list. Also, anyone who doesn't receive new posts via email but would like to, please sign up via the Subscribe by Email box on the left-hand sidebar of the blog.

Thanks so much for reading my posts, however you choose to do so!

Software changes can be annoying, but free technology services don't last forever, and I'm glad FeedBurner has been up and running reliably for so long.

Since I got the news about the change, I've been looking for another product so that readers could receive new blog posts via email, and finally settled on Mailchimp.

I plan to migrate the list of email subscribers to the new Mailchimp platform over Memorial Day weekend in the US (May 29-31). If you're currently subscribed via email, you'll continue to be subscribed after the move. I expect everything will go smoothly (fingers crossed!).

The new emails will be coming from my address rather than from Google.com, so if you're a subscriber, you may want to add my email (sarah at readingthepast dot com) to your approved senders list so you don't miss anything.

Anyone who signed up for email updates within the last two weeks is already on the new mailing list. Also, anyone who doesn't receive new posts via email but would like to, please sign up via the Subscribe by Email box on the left-hand sidebar of the blog.

Thanks so much for reading my posts, however you choose to do so!

Thursday, May 20, 2021

Review of the final book in Alison Weir's Six Tudor Queens Series: Katharine Parr, The Sixth Wife

Henry VIII was neither her first nor her last husband, yet it’s Katharine Parr’s status as his sixth wife, naturally, that commands the most attention. Weir’s admirable conclusion to her Six Tudor Queens series reveals Katharine as a woman of intellect, kindness, and strategic acumen who plays the long game to attain her heart’s desires.

Twice-widowed when she marries Henry, she brings a diverse range of experiences to her queenship. Weir smoothly knits all these life segments together, showing how Katharine’s background shapes her character and beliefs.

Raised amid a loving family that respects women’s education, she first weds a nobleman’s son and secondly an older, Catholic baron. The story strikes a clear path through the complicated political and religious circumstances of 1520s-40s England as the action sweeps from Lincolnshire to Yorkshire during the Pilgrimage of Grace to dazzling London.

In choosing Henry over personal happiness, Katharine, secretly Protestant, seeks to guide the realm in that direction. She comes to love the King, despite his age and infirmities, but influential women tend to acquire enemies.

Her relations with her stepchildren are handled with realistic nuance, and Henry’s death drops her into intense romantic intrigue. This wide-ranging novel expertly showcases Katharine’s courageous, eventful life and many noteworthy accomplishments.

Katharine Parr, The Sixth Wife was published by Ballantine this month in the US, and by Headline Review in the UK. I wrote this review for Booklist and it appeared in the April 15th issue.

This is the fifth book in the series I've reviewed... all except the first book, which focused on Katherine of Aragon. This book and the third, Jane Seymour, The Haunted Queen, are my favorites. With this one, I particularly liked how Weir devoted so much time to Katharine's life before her marriage to Henry VIII; she was well-educated and traveled quite a bit within England. She had five stepchildren in all, including, of course, the future Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I.

Now that this series is complete, I wonder what direction Weir will take next with her fiction.

Twice-widowed when she marries Henry, she brings a diverse range of experiences to her queenship. Weir smoothly knits all these life segments together, showing how Katharine’s background shapes her character and beliefs.

Raised amid a loving family that respects women’s education, she first weds a nobleman’s son and secondly an older, Catholic baron. The story strikes a clear path through the complicated political and religious circumstances of 1520s-40s England as the action sweeps from Lincolnshire to Yorkshire during the Pilgrimage of Grace to dazzling London.

In choosing Henry over personal happiness, Katharine, secretly Protestant, seeks to guide the realm in that direction. She comes to love the King, despite his age and infirmities, but influential women tend to acquire enemies.

Her relations with her stepchildren are handled with realistic nuance, and Henry’s death drops her into intense romantic intrigue. This wide-ranging novel expertly showcases Katharine’s courageous, eventful life and many noteworthy accomplishments.

Katharine Parr, The Sixth Wife was published by Ballantine this month in the US, and by Headline Review in the UK. I wrote this review for Booklist and it appeared in the April 15th issue.

This is the fifth book in the series I've reviewed... all except the first book, which focused on Katherine of Aragon. This book and the third, Jane Seymour, The Haunted Queen, are my favorites. With this one, I particularly liked how Weir devoted so much time to Katharine's life before her marriage to Henry VIII; she was well-educated and traveled quite a bit within England. She had five stepchildren in all, including, of course, the future Edward VI, Mary I, and Elizabeth I.

Now that this series is complete, I wonder what direction Weir will take next with her fiction.

Sunday, May 16, 2021

Trendspotting: the many new historical novels with "Last" in their titles

Have you noticed that the titles of many new historical novels have a certain air of finality?

The novels above are all from 2021. And that's not the last of them. It wasn't until I'd read and reviewed a few of these that I realized how many "Last" titles there were.

(Shown above: The Last Tiara by M.J. Rose; The Last Garden in England by Julia Kelly; The Last Green Valley by Mark Sullivan; The Last Night in London by Karen White; The Last Bookshop in London by Madeline Martin; The Last One Home by Shari J. Ryan.)

But that's not all. Searching online quickly brought up many more. There were so many titles to choose from that I had to be selective.

The novels above are all from 2021. And that's not the last of them. It wasn't until I'd read and reviewed a few of these that I realized how many "Last" titles there were.

(Shown above: The Last Tiara by M.J. Rose; The Last Garden in England by Julia Kelly; The Last Green Valley by Mark Sullivan; The Last Night in London by Karen White; The Last Bookshop in London by Madeline Martin; The Last One Home by Shari J. Ryan.)

But that's not all. Searching online quickly brought up many more. There were so many titles to choose from that I had to be selective.

(Above: Last Night at the Telegraph Club by Malinda Lo; The Last Bathing Beauty by Amy Sue Nathan; The Last Dance of the Debutante by Julia Kelly, forthcoming; The Last Days of Ellis Island by Gaelle Josse; The Last Mona Lisa by Jonathan Santlofer; The Last Checkmate by Gabriella Saab. These last two are out later this year.)

When you think about it, "Last" titles are a natural fit for historical novels, as they signal the depiction of a time or event that has since faded into the past.

(Above: The Last Train to London by Meg Waite Clayton; Her Last Flight by Beatriz Williams; Millicent Glenn's Last Wish by Tori Whitaker; The Last Passenger by Charles Finch; The Last Tea Bowl Thief by Jonelle Patrick; The Last Train to Key West by Chanel Cleeton.)

When you think about it, "Last" titles are a natural fit for historical novels, as they signal the depiction of a time or event that has since faded into the past.

(Above: The Last Train to London by Meg Waite Clayton; Her Last Flight by Beatriz Williams; Millicent Glenn's Last Wish by Tori Whitaker; The Last Passenger by Charles Finch; The Last Tea Bowl Thief by Jonelle Patrick; The Last Train to Key West by Chanel Cleeton.)

I'm sure we aren't seeing the last of this title trend.

Friday, May 14, 2021

Chanel Cleeton's The Most Beautiful Girl in Cuba follows three bold women during the Cuban War of Independence

Chanel Cleeton’s fourth historical novel explores the nature of freedom on multiple levels, from the dynamics of international politics to the individual dilemmas of three bold women. They all become embroiled, in different ways, in Cuba’s fight for independence. They also find themselves caught between society’s expectations and the images they want to craft for themselves.

Set in the late 19th century, the book’s subject is the lead-up to the Spanish-American War, an event rarely touched upon in historical fiction, especially from the female viewpoint.

As the Cuban people strive to overturn the repressive rule of their Spanish colonizers, Evangelina Cisneros, a young Cuban woman, is thrust into a grim women’s prison in Havana under false political charges. She’s a historical figure, and her plotline aligns with real-life history. The other two protagonists are Grace Harrington, an American newspaper journalist working for William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal, and Marina Perez, a Cuban farmer’s wife forced to leave her home with her family, travel across the ruined countryside, and endure dire conditions in a reconcentration camp.

It takes a little while to get used to all three viewpoints and the switches among them, but the stories come together in a powerful way.

Competition between Hearst’s paper and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World is cutthroat, and Grace places herself in the thick of it. Operating under the principle that it’s important not just to report on the news, but act on it, the Journal aims to pressure the United States into backing Cuban independence. When Hearst learns about Evangelina languishing in prison, the paper takes her up as a symbol of injustice, declares her the “most beautiful girl in Cuba,” and plans to break her out. Under the guise of a laundress, Marina delivers secret messages for the rebels while worrying desperately about her beloved husband, who’s separated from her and their daughter while fighting for freedom.

I thoroughly enjoyed this multifaceted view of this pivotal historical time: the view of late 19th-century Cuba from the Cuban and American perspectives, the action-intensive plot, and the women’s different but equally touching love stories. Their emotionally grabbing quests for self-determination run alongside that of Cuba in this wide-ranging and page-turning tale.

Set in the late 19th century, the book’s subject is the lead-up to the Spanish-American War, an event rarely touched upon in historical fiction, especially from the female viewpoint.

As the Cuban people strive to overturn the repressive rule of their Spanish colonizers, Evangelina Cisneros, a young Cuban woman, is thrust into a grim women’s prison in Havana under false political charges. She’s a historical figure, and her plotline aligns with real-life history. The other two protagonists are Grace Harrington, an American newspaper journalist working for William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal, and Marina Perez, a Cuban farmer’s wife forced to leave her home with her family, travel across the ruined countryside, and endure dire conditions in a reconcentration camp.

It takes a little while to get used to all three viewpoints and the switches among them, but the stories come together in a powerful way.

Competition between Hearst’s paper and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World is cutthroat, and Grace places herself in the thick of it. Operating under the principle that it’s important not just to report on the news, but act on it, the Journal aims to pressure the United States into backing Cuban independence. When Hearst learns about Evangelina languishing in prison, the paper takes her up as a symbol of injustice, declares her the “most beautiful girl in Cuba,” and plans to break her out. Under the guise of a laundress, Marina delivers secret messages for the rebels while worrying desperately about her beloved husband, who’s separated from her and their daughter while fighting for freedom.

I thoroughly enjoyed this multifaceted view of this pivotal historical time: the view of late 19th-century Cuba from the Cuban and American perspectives, the action-intensive plot, and the women’s different but equally touching love stories. Their emotionally grabbing quests for self-determination run alongside that of Cuba in this wide-ranging and page-turning tale.

The Most Beautiful Girl in Cuba was published by Berkley on May 4th; I read it from a NetGalley copy.

Tuesday, May 11, 2021

Books shine a light during dark times in The Last Bookshop in London by Madeline Martin

As you can guess, Madeline Martin’s The Last Bookshop in London is a book about books. It celebrates the power of literature to whisk you out of “real life” and into a different, wholly realized world filled with characters you come to care about. Furthermore, it accomplishes this feat itself.

Martin is a prolific writer of historical romance; this is her first work of mainstream historical fiction, and I hope she stays in this new genre a while longer. Her story manages to be simultaneously inspiring and unflinchingly realistic in its depiction of Londoners enduring the Blitz.

In 1939, Grace Bennett and her best friend, Viv, leave their sleepy Norfolk village and head to London, where they share a room in the comfortable house owned by Mrs. Weatherford, a childhood friend of Grace’s late mother. They both need work, and Grace needs a reference, since her unpleasant uncle, whose shop she worked in, refused to give her one.

Mrs. Weatherford cajoles the grumpy proprietor of the Primrose Hill Bookshop, Mr. Evans, into employing Grace as an assistant for six months. He warns Grace not to get attached to the place, whose dusty, disorganized shelves have their own eccentric charm. Grace works hard in cleaning and rearranging the books, and one frequent customer, the handsome George Anderson, introduces her to the love of reading. As for Mr. Evans, one quickly suspects he has a soft heart under all the bluster.

Through Grace, Martin presents an on-the-ground view of London’s people and streets as the rumbles of war grow louder. Men are called up, including Mrs. Weatherford’s gentle son; children line up to be evacuated to the countryside; wives and mothers join service organizations while worrying about their loved ones’ safety. Many images here will stay with me, thanks to well-placed period details. We see the white chairs and bright yellow towels in Mrs. Weatherford’s homely kitchen and the Anderson air-raid shelter (the “Andy”) in her back garden. During the Blitz, as German bombs fall, we see the various ways Londoners react to these devastating strikes on their neighborhoods: some readily seek shelter, while others, tired of these nightly occurrences, start refusing to leave their homes.

Through it all, Grace and her customers take refuge in stories, which they find a wonderful distraction. We get to experience the appeal of many classic novels as Grace discovers them for herself. Being interested in literary history, I found it especially enlightening to learn about the new books that became top sellers at the bookshop, which ones flopped, and why. After reading about it here, Winifred Holtby’s South Riding is the latest addition to my to-be-read stack.

It’s not surprising that The Last Bookshop in London has been on bestseller lists. It’s an absorbing crowd-pleaser of a novel about preserving hope during dark times, a theme that many of us today can get behind.

The Last Bookshop in London was published by Hanover Square in April. Thanks to the publisher for approving a NetGalley copy.

Martin is a prolific writer of historical romance; this is her first work of mainstream historical fiction, and I hope she stays in this new genre a while longer. Her story manages to be simultaneously inspiring and unflinchingly realistic in its depiction of Londoners enduring the Blitz.

In 1939, Grace Bennett and her best friend, Viv, leave their sleepy Norfolk village and head to London, where they share a room in the comfortable house owned by Mrs. Weatherford, a childhood friend of Grace’s late mother. They both need work, and Grace needs a reference, since her unpleasant uncle, whose shop she worked in, refused to give her one.

Mrs. Weatherford cajoles the grumpy proprietor of the Primrose Hill Bookshop, Mr. Evans, into employing Grace as an assistant for six months. He warns Grace not to get attached to the place, whose dusty, disorganized shelves have their own eccentric charm. Grace works hard in cleaning and rearranging the books, and one frequent customer, the handsome George Anderson, introduces her to the love of reading. As for Mr. Evans, one quickly suspects he has a soft heart under all the bluster.

Through Grace, Martin presents an on-the-ground view of London’s people and streets as the rumbles of war grow louder. Men are called up, including Mrs. Weatherford’s gentle son; children line up to be evacuated to the countryside; wives and mothers join service organizations while worrying about their loved ones’ safety. Many images here will stay with me, thanks to well-placed period details. We see the white chairs and bright yellow towels in Mrs. Weatherford’s homely kitchen and the Anderson air-raid shelter (the “Andy”) in her back garden. During the Blitz, as German bombs fall, we see the various ways Londoners react to these devastating strikes on their neighborhoods: some readily seek shelter, while others, tired of these nightly occurrences, start refusing to leave their homes.

Through it all, Grace and her customers take refuge in stories, which they find a wonderful distraction. We get to experience the appeal of many classic novels as Grace discovers them for herself. Being interested in literary history, I found it especially enlightening to learn about the new books that became top sellers at the bookshop, which ones flopped, and why. After reading about it here, Winifred Holtby’s South Riding is the latest addition to my to-be-read stack.

It’s not surprising that The Last Bookshop in London has been on bestseller lists. It’s an absorbing crowd-pleaser of a novel about preserving hope during dark times, a theme that many of us today can get behind.

The Last Bookshop in London was published by Hanover Square in April. Thanks to the publisher for approving a NetGalley copy.

Sunday, May 09, 2021

Those Who Are Saved by Alexis Landau, a tense novel of motherly love during WWII

Times of war force people into agonizing decisions with haunting repercussions. In her uneven yet hard-hitting sophomore novel, Landau (The Empire of the Senses, 2015) introduces Vera Volosenkova, a wealthy Russian Jewish immigrant in 1940 France.

After receiving notice to report for internment, she and her husband, Max, worried about conditions in the camp, place their four-year-old daughter, Lucie, into her governess Agnes’ care. They assume they won’t be away long, and Agnes “can always bring Lucie home with her to Oradour-sur-Glane,” Vera reasons.

Nearly five years later, in California, Vera contemplates her broken marriage and stalled writing career. She and Max were unable to reclaim Lucie before escaping, and Vera constantly second-guesses her choice. Subsumed by anxiety and feeling lost, Vera begins an affair with a Hollywood screenwriter, Sasha, a kind man with a complicated past.

The plot feels fragmented and slow midway through, and anyone familiar with French WWII history will guess the basic outline. Landau confidently illuminates her settings and her characters’ psyches, though, and Vera’s unwavering resolve to find Lucie amid the chaos of postwar France feels arrestingly real.

Those Who Are Saved was published by Putnam in February; I wrote this review for Booklist's Jan 1 issue (reprinted with permission).

After receiving notice to report for internment, she and her husband, Max, worried about conditions in the camp, place their four-year-old daughter, Lucie, into her governess Agnes’ care. They assume they won’t be away long, and Agnes “can always bring Lucie home with her to Oradour-sur-Glane,” Vera reasons.

Nearly five years later, in California, Vera contemplates her broken marriage and stalled writing career. She and Max were unable to reclaim Lucie before escaping, and Vera constantly second-guesses her choice. Subsumed by anxiety and feeling lost, Vera begins an affair with a Hollywood screenwriter, Sasha, a kind man with a complicated past.

The plot feels fragmented and slow midway through, and anyone familiar with French WWII history will guess the basic outline. Landau confidently illuminates her settings and her characters’ psyches, though, and Vera’s unwavering resolve to find Lucie amid the chaos of postwar France feels arrestingly real.

Those Who Are Saved was published by Putnam in February; I wrote this review for Booklist's Jan 1 issue (reprinted with permission).

The novel is interlinked with the author's debut, The Empire of the Senses (which I loved), via its secondary characters. It can easily be read alone.

Tuesday, May 04, 2021

Hour of the Witch by Chris Bohjalian, a thrilling novel of 17th-century New England

How far will a woman go to escape an abusive husband? In Puritan Boston in 1662, divorces are rarely granted, but Mary Deerfield, a beautiful 24-year-old goodwife, sees no alternative. Barren after five years of marriage to Thomas, a prosperous miller in his mid-forties, Mary conceals bruises beneath her coif and brushes off concerns from her adult stepdaughter.

Thomas has a pattern of returning “drink-drunk” from the tavern, taking his anger out on Mary, and apologizing the next morning. Their indentured servant, who admires Thomas, never sees any violence, only a husband properly correcting his wife. Then comes the evening when Thomas attacks Mary’s left hand with a fork.

Mary has allies, most notably her caring, wealthy parents. But in a culture that views women as subservient helpmeets, and with no witnesses to Thomas’s cruelty, Mary’s petition has slim chances. She must also tread carefully: the Hartford witch-hunts weigh on people’s minds, some of her behavior appears suspicious, and Satan’s temptations lurk everywhere.

Themes of women’s agency in a patriarchal society are common in historical novels, but this fast-moving, darkly suspenseful novel stands out with Bohjalian’s extraordinary world-building skills. From speech patterns to the detailed re-creation of colonial households to the religious mindset, the historical setting is very credible.

The rich have finer options—Mary’s mother wears vivid colors, for instance—but her father struggles to get across that the three-pronged forks he imports from abroad are just utensils, not the “Devil’s tines.” Mary isn’t an outspoken iconoclast but a product of her era, and readers will worry for her—for many reasons, which become clear as the story progresses.

The quotes opening each chapter, taken from court proceedings occurring later on, diminish some of the novel’s surprises. Nonetheless, the plot moves with increasing urgency that will have readers racing toward the ending.

Hour of the Witch is published today by Doubleday; I reviewed it from NetGalley for the Historical Novels Review. If this doesn't convince you to read it, also check out Diana Gabaldon's recent review for the Washington Post.

Thomas has a pattern of returning “drink-drunk” from the tavern, taking his anger out on Mary, and apologizing the next morning. Their indentured servant, who admires Thomas, never sees any violence, only a husband properly correcting his wife. Then comes the evening when Thomas attacks Mary’s left hand with a fork.

Mary has allies, most notably her caring, wealthy parents. But in a culture that views women as subservient helpmeets, and with no witnesses to Thomas’s cruelty, Mary’s petition has slim chances. She must also tread carefully: the Hartford witch-hunts weigh on people’s minds, some of her behavior appears suspicious, and Satan’s temptations lurk everywhere.

Themes of women’s agency in a patriarchal society are common in historical novels, but this fast-moving, darkly suspenseful novel stands out with Bohjalian’s extraordinary world-building skills. From speech patterns to the detailed re-creation of colonial households to the religious mindset, the historical setting is very credible.

The rich have finer options—Mary’s mother wears vivid colors, for instance—but her father struggles to get across that the three-pronged forks he imports from abroad are just utensils, not the “Devil’s tines.” Mary isn’t an outspoken iconoclast but a product of her era, and readers will worry for her—for many reasons, which become clear as the story progresses.

The quotes opening each chapter, taken from court proceedings occurring later on, diminish some of the novel’s surprises. Nonetheless, the plot moves with increasing urgency that will have readers racing toward the ending.

Hour of the Witch is published today by Doubleday; I reviewed it from NetGalley for the Historical Novels Review. If this doesn't convince you to read it, also check out Diana Gabaldon's recent review for the Washington Post.

Saturday, May 01, 2021

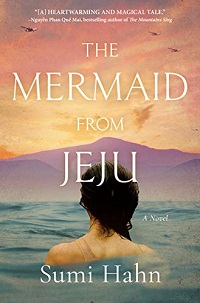

The Mermaid from Jeju by Sumi Hahn, a story of war and family in 20th-century Korea

Korean-born, New Zealand-based author Hahn debuts with a poignant, original book about women’s strength, the human cost of war, and how people come to terms with painful memories. Korea’s Jeju Island is the stunningly rendered setting.

Goh Junja is a young diver of Jeju who, like her mother and grandmother, plunges to the sea floor to collect delicacies to feed her village. Lisa See (The Island of Sea Women) and Mary Lynn Bracht (White Chrysanthemum) have also written novels about these female divers, called haenyeo, and anyone who enjoyed either should read this one, too. They share a wartime setting but differ in style and theme.

The Mermaid from Jeju opens, unusually, with the death of the main character, a doctor’s wife in 2001 Philadelphia, then jumps back to 1944. Eighteen-year-old Junja, having come into her power as a haenyeo after surviving a near-drowning, convinces her mother to let her make the annual trek to Hallasan, a distant mountain, in her place to trade abalone for a piglet. While there, Junja grows intrigued by Suwol, the noble eldest son of the house, and he with her. She returns to Jeju to face her mother’s tragic death, reportedly after a fatal dive. Meanwhile, in the postwar era, the political situation throughout Korea has grown treacherous: the Japanese occupiers have fled, the Americans are landing, and Nationalist forces are tracking down potential communist sympathizers.

The story immerses readers wholly in the culture and history of Jeju, from a terrible real-life tragedy to local myths and elements of Korean spirituality. On the one hand, it’s never didactic; on the other, some aspects don’t become clear to Junja until later, which creates a certain vagueness. When Junja’s widower visits Korea to lay his ghosts to rest, it crystallizes the plot and brings events full circle in a satisfying and meaningful way.

The Mermaid from Jeju was published by Alcove Press in 2020; I reviewed it from a purchased copy for May's Historical Novels Review.

When my husband saw the title of this book, he asked about the setting and then mentioned he'd been to the island, which he called Cheju-do (Cheju island), when he was stationed in Korea with the US Army in 1979-80. Below is one picture he took there, to provide a sense of the geographic landscape. Jeju, a volcanic island, is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Goh Junja is a young diver of Jeju who, like her mother and grandmother, plunges to the sea floor to collect delicacies to feed her village. Lisa See (The Island of Sea Women) and Mary Lynn Bracht (White Chrysanthemum) have also written novels about these female divers, called haenyeo, and anyone who enjoyed either should read this one, too. They share a wartime setting but differ in style and theme.

The Mermaid from Jeju opens, unusually, with the death of the main character, a doctor’s wife in 2001 Philadelphia, then jumps back to 1944. Eighteen-year-old Junja, having come into her power as a haenyeo after surviving a near-drowning, convinces her mother to let her make the annual trek to Hallasan, a distant mountain, in her place to trade abalone for a piglet. While there, Junja grows intrigued by Suwol, the noble eldest son of the house, and he with her. She returns to Jeju to face her mother’s tragic death, reportedly after a fatal dive. Meanwhile, in the postwar era, the political situation throughout Korea has grown treacherous: the Japanese occupiers have fled, the Americans are landing, and Nationalist forces are tracking down potential communist sympathizers.

The story immerses readers wholly in the culture and history of Jeju, from a terrible real-life tragedy to local myths and elements of Korean spirituality. On the one hand, it’s never didactic; on the other, some aspects don’t become clear to Junja until later, which creates a certain vagueness. When Junja’s widower visits Korea to lay his ghosts to rest, it crystallizes the plot and brings events full circle in a satisfying and meaningful way.

The Mermaid from Jeju was published by Alcove Press in 2020; I reviewed it from a purchased copy for May's Historical Novels Review.

When my husband saw the title of this book, he asked about the setting and then mentioned he'd been to the island, which he called Cheju-do (Cheju island), when he was stationed in Korea with the US Army in 1979-80. Below is one picture he took there, to provide a sense of the geographic landscape. Jeju, a volcanic island, is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

|

| 300-foot cliff on Jeju island, off the southern coast of Korea |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)