Good reading to all of you in the New Year!

Countless historical novels use long-hidden love letters to cinch the connection between two parallel narratives. Kayte Nunn’s The Forgotten Letters of Esther Durrant, set on the Isles of Scilly near Cornwall, shows how a talented author can revitalize this trope and make it distinctive and unexpected. Moving between the early 1950s and 2018, the story evokes the rustic coastal beauty of its isolated setting as it follows a marine scientist’s uncovering of a young mother’s forced stay at an island sanitarium.

A blurb on the back of Tracy Rees’ Florence Grace (from fellow novelist Joanna Courtney) describes it as “so very wise, as if it contains half the answers to life.” The quote is actually accurate. Florrie Buckley, an orphaned teenager from a remote corner of Cornwall in 1850, comes into a surprising inheritance and moves to join her newfound relatives in London, where she slowly adjusts to upper-class ways and forms new relationships but remains uniquely herself. Full of entertaining personalities and the protagonist’s lively narration, with a good balance of light and dark.

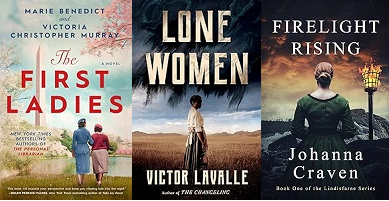

Victor LaValle’s dark historical fantasy Lone Women opens with a shocker: Adelaide Henry, daughter in a Black farming family in 1915 California, flees the scene of her parents’ brutal murder for a homesteading site in Montana, toting a painfully heavy trunk too dangerous to be opened. Let’s just say I had questions. As a “lone woman” in a harsh environment, Adelaide must form alliances with other would-be settlers but needs to discover who to trust. Inventive and not for the squeamish, this novel is a defiantly original take on the multicultural settlement of the American West.

Anyone who’s traveled to the Holy Isle of Lindisfarne in Northumberland knows it’s a special place. First in a trilogy, Johanna Craven’s Firelight Rising takes place there in 1715, as Eva Blake, her siblings, and their families have grudgingly returned after two decades' absence, just as an underground Jacobite movement is stirring. As the Blakes restore their decrepit home, they contend with mysteries of the past and present-day dangers. A highly atmospheric story brimming with romance and mystery and a stellar sense of place.

Historical Stories of Exile is an anthology of thirteen short stories, each taking a different angle on its theme. All of the authors are talented historical novelists, and their contributions provide an appealing assortment of settings. Among my favorites were Anna Belfrage’s “The Unwanted Prince,” the heartbreaking true story of a young boy forced to part from his home and loving mother; Cryssa Bazos’ “The Exiled Heart,” retelling the love story between Prince Rupert of the Palatinate and his jailer’s daughter in Austria; Elizabeth St.John’s “Into the Light,” a 17th-century tale of religious disharmony and new beginnings; and Amy Maroney’s “Last Hope for a Queen,” evoking the valiant spirit of Queen Charlotta of Cyprus in the 15th century.

The Pilot’s Daughter by Meredith Jaeger is another dual-narrative story, split between the late WWII years and Jazz Age New York. An office girl at the San Francisco Chronicle, recently informed of her pilot father’s MIA status, comes upon love letters intimating that he’d had an affair. For answers, she turns to her aunt Iris, who has her own secret past as one of Ziegfeld’s dancers in the ‘20s. An engrossing novel about meeting life on its own terms, partly inspired by a real-life crime, the murder of the flapper called the “Broadway Butterfly.”

The Weight of Ink by Rachel Kadish tightly interweaves the stories of two modern academics, a stern older woman and a male American grad student who's used to charming his way into people's good graces, with that of a young Sephardic Jewish woman who handles correspondence for a blind rabbi in exile in Restoration-era London. As the modern pair uncover details about the scribe who signed herself “Aleph,” a deeper succession of mysteries unfolds. Over 500 pages long, brilliant on a sentence level and in its entirety, this National Jewish Book Award winner somehow achieves thriller-like pacing as it celebrates the undeniable quest for learning and delves into perennial human themes. This is right up there with A.S. Byatt’s Possession in my view, and more accessible. A magnificent read.