A superb achievement, Pulitzer Prize-winner Harding’s (Enon, 2013) third novel fictionalizes a shameful true episode from American history. In 1912, the mixed-race residents of Malaga Island off Maine’s coast, people living there for generations, were forcibly removed for reasons of “public health” and tourism development. The pseudoscience of eugenics lay behind the decision.

In Harding’s version, Esther Honey is the matriarch of a poor, close-knit family of African and Irish descent; other residents on Apple Island include the Lark family, the McDermott sisters, their Penobscot foster children, and eccentric carpenter Zachary Hand to God Proverbs.

When retired schoolteacher Matthew Diamond arrives to preach and educate the island’s young people, he recognizes his prejudice but finds several gifted pupils, including 15-year-old, light-skinned Ethan Honey, a talented artist. Events spiral downward when a committee from the Governor’s Council takes notice and comes to investigate. The injustice they impose feels infuriating.

Harding combines an engrossing plot with deft characterizations and alluring language deeply attuned to nature’s artistry. The biblical parallels, which naturally align with the characters’ circumstances, add depth and enhance the universality of the themes.

Readers must gingerly parse some winding, near-paragraph-long sentences, but this gorgeously limned portrait about family bonds, the loss of innocence, the insidious effects of racism, and the innate worthiness of individual lives will resonate long afterward.

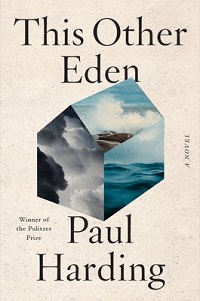

This Other Eden was one of the best novels I read in 2022, and it will be published next week by W.W. Norton. I wrote this review for Booklist's December 1st issue.

For more background on Malaga Island along with photographs, please see the article The Shameful Story of Malaga Island by historian William David Barry, published in Down East magazine in November 1980. Also, per Wikipedia: "On April 7, 2010, Maine legislators finally issued an official statement of regret for the Malaga incident, but did so without notifying descendants and other stakeholders either before or after the fact. The 'public' apology didn't become known to the public until nearly four months later, when an article appeared in a monthly magazine, Down East, which also procured a statement of regret by Governor John Baldacci."

▼

About Me

- Sarah Johnson

- Collection management librarian, readers' advisor, avid historical fiction reader, NBCC member. Book review editor for the Historical Novels Review and Booklist reviewer. Recipient of ALA's Louis Shores Award for book reviewing (2012). Blogging since 2006.

No comments:

Post a Comment