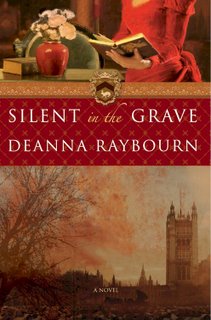

Last April, I spotted Deanna Raybourn's Silent in the Grave in Publisher's Weekly's list of "galleys to grab" at BookExpo America, and blogged about it. While at BEA in DC in June, I met Deanna at her signing booth, and we chatted about the blog, historical fiction in general, and the exciting "headless woman" treatment her novel was going to get (at left; the cover of the galley I received showed an earlier version).

Last April, I spotted Deanna Raybourn's Silent in the Grave in Publisher's Weekly's list of "galleys to grab" at BookExpo America, and blogged about it. While at BEA in DC in June, I met Deanna at her signing booth, and we chatted about the blog, historical fiction in general, and the exciting "headless woman" treatment her novel was going to get (at left; the cover of the galley I received showed an earlier version).Silent in the Grave begins a trilogy starring Lady Julia Grey, an unwitting and unlikely amateur detective. Her adventure begins in 1866. Her inattentive husband, Sir Edward Grey, has just collapsed and died during a dinner party at his London townhouse. The family doctor blames Edward’s longstanding heart condition, and Julia believes him, despite suggestions by Edward’s private inquiry agent, Nicholas Brisbane, that it was murder. It’s over a year later when Julia comes across compelling evidence that proves Brisbane was right. She engages Brisbane’s services, and during their investigation, she uncovers unpleasant and frequently sordid facts about her late husband’s behavior, as well as surprising truths about herself.

Despite its length, Silent in the Grave is a gripping, fast-paced read that balances its darker aspects with deft humor, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Deanna is a sixth-generation Texan who now makes her home in a Virginia college town. Silent in the Grave is her first novel. More information can be found at her website, www.deannaraybourn.com, or her novel's site, www.silentinthegrave.com.

What attracted you to Victorian England?

Oddly enough, the book was initially conceived as a Regency piece. I wrote the first fifty pages or so with an 1816 setting before I decided it needed to be changed. The Regency was a frothy and sparkling time and dictated a different voice for Julia. Moving the action sixty or seventy years further into the nineteenth century changed that voice entirely. It brought in something darker and edgier, and I think the repression and shadowed sexuality of the Victorians is much more in keeping with the story than the vivacity and lightness of Regency manners. It also changed the domestic technology, so that necessitated a fresh batch of research. I gnashed my teeth for awhile over that, but ultimately it served the book much better to change the historical setting.

Lady Julia narrates her story in the first person, which is somewhat unusual for a historical mystery. Why did you choose to write from her viewpoint, and how did you create her voice?

I actually didn’t choose the viewpoint. Very early on in the plotting phase the first line popped into my head, and I loved it. That established the voice, and it felt right for the book so I went with it.

The members of Julia's family, the Marches, are quite eccentric, to say the least. Are any of them based on real people, historical or otherwise?

The Marches are entirely original. Throughout history, the English aristocracy has been loaded with deliciously eccentric characters, most of them far more outrageous than the Marches. In the case of the Marches, it may have arrested their development a bit as well by allowing them to follow their own whims. The typical person on the street may have their caprices, but they can’t give way to them because they have a job to hold down or children to raise or a house to keep or they’re afraid of what the neighbors might think. The Marches are rich enough to indulge their follies and highly-born enough not to care for anyone’s opinion. Taken as a whole, they remind me a bit of the Mitfords, but they aren’t based on any particular family.

Silent in the Grave includes a fair amount of detail on medicine, and medical research, in Victorian times. How did you go about researching this?

The Internet is a glorious thing. Before researching this book, I had only ever used it for shopping or e-mail, but with this story, I learned how to ferret out pretty much anything I needed to know. I still made endless trips to the library; I consulted a helpful urologist; I e-mailed a staff member at the University of Edinburgh medical school, but for quick fact-checking, nothing beats the Internet.

One of the aspects I enjoyed most was that despite the dark atmosphere, which became more and more pervasive toward the end, you incorporate a good amount of humor into the novel. For example - Julia's morbid Aunt Ursula (aka "the Ghoul"), the missing Tower raven, and the wry comments Julia utters on occasion. I wonder if you could talk a little about the role of humor in historical fiction, and in Silent in the Grave in particular – why was it important to you?

Humor is tremendously important, particularly in historical fiction because it humanizes characters who can so easily stray into sounding pedantic or dry without it. On the other hand, it is essential to use it subtly or the historic atmosphere is shattered. And there are different kinds of humor in the book. Julia banters with her sister, Portia, and they trade friendly insults, but that interaction is completely different in tone from the scathing sarcasm she might direct at Nicholas, or the wryness of her personal observations in the narrative. Humorous characters, such as the Ghoul, were put in deliberately to lighten the tone of the book and provide a balance to the darker elements. I didn’t want the grim circumstances of a murder investigation to define the relationships in the book. It was important to me that real life peek around the curtains and wink at the reader from time to time.

On p.260, Julia comments that she "adored history, not the dry dates and boring battles, but the stories and people who populated them." Does her statement reflect your own views on history as well - and if not, how do they differ?

History can be painfully dry. The key to making it come alive is not to neglect the human element. Everyone knows Wellington decimated Napoleon at Waterloo, but the story becomes much more interesting when you discover that part of Napoleon’s defeat allegedly came from his inability to mount a horse and survey the battlefield due to raging hemorrhoids. Bloody Mary Tudor becomes a great deal less monstrous and much more pitiful when you move past the burnings at Smithfield and realize she was so desperate to have a child she managed to mistake terminal cancer for a pregnancy she joyfully announced to the court. Facts are only as interesting as the stories behind them.

One scene finds Julia glancing at books in her study, reminiscing about treasured reads from her youth. She remarks that many were "romantic stories with dark, brooding men with mysterious pasts and scornful glances" which, to her anger and chagrin, left her with an overactive imagination. Nicholas Brisbane fits the image of the classic tortured hero in some ways, but not in others. How did you develop his character?

Julia just sprang from my head like Athena, fully-formed. Nicholas was WORK. I did start with the idea of dark and brooding because I wanted a man who would quicken Julia’s pulse and play into her fantasies, but I wanted him flawed, deeply and perhaps irreparably flawed. I knew there had to be some experimentation on his part with illicit substances, but I wanted it to be from medical necessity. I wanted Nicholas to be full of contradictions: from a good family, but socially questionable; of aristocratic blood, but mixed with something else; well-connected, but technically in trade. And I knew he needed a mysterious past full of secrets even I don’t know. He has traveled the world, and on his travels he has collected scars and souvenirs and arcane bits of knowledge that are occasionally useful. The one thing he has never found is a woman as engaging as Julia Grey. Ultimately, I wanted to create a character so complex that even if Julia did end up spending the whole of her life with him, she would never fully understand him.

Throughout the novel, I noticed you took care to use British spellings and terminology. As an American author writing about historical England, what are some other cross-cultural issues you felt you had to pay special attention to? How did you get into the mindset for writing about Victorian times?

My reading is primarily British, which helps enormously. Besides the obvious research materials, I read novels either set or written in the time period. If I’m in the mood to putter in the kitchen, I read Nigella Lawson or Rita Konig rather than American authors. If I’m thinking about gardens, I pull out my Beverley Nichols. Even if I’m taking a break from “work” mode and reading something frothy, it’s usually British chick lit, not American. There is something about British writing that manages to be both exotic and extremely comforting at the same time. One of the most gratifying compliments I’ve received was from the head of my publisher’s UK office; he was surprised the writer was American—he assumed I was British! But my father is only a first-generation American, so I’m not too far removed in any case. For me, the most difficult aspect was not establishing a British voice, it was establishing an upper-class, nineteenth-century voice. The aristocracy inhabits a rarified world that can be extremely difficult for an outsider to comprehend. But the more I read, the more I realized how little has changed. If you go beyond formal writing and read personal correspondence or diaries, Victorians could be strikingly informal and recognizable to a modern reader.

What are some of the more interesting or odd facts you uncovered during the research process?

I borrowed a textbook from a kindly urologist full of pictures that still give me nightmares. It was useful, but VERY disturbing.

With your double major in English and history, it seems almost logical that you ended up writing historical fiction. What about the genre attracted you?

Actually, it happened the other way around. I double-majored in English and history because I wanted to write historical fiction. I wasn’t entirely certain what specific genre I wanted to target, but I had always written, and what I wrote was always set in the past. My English courses taught me dramatic structure, how to pick apart characters, how to look at a story from a critical standpoint; my history courses taught me research skills. Both disciplines have proven extremely helpful, perhaps English more so.

Thanks, Deanna, for your willingness to do the interview. Silent in the Grave was published in January 2007 by MIRA ($21.95 US / $26.95 Can) in hardback, 509pp, ISBN 0-7783-2410-9.

Great interview! I'll have to look for this one.

ReplyDeleteSounds like another book for my To Buy list.

ReplyDeleteReally, the internet is a dnagerous place; that To Buy list totally doesn't sync with my purse and blogs like yours don't improve that. :)

My apologies. That's a big problem for me too.

ReplyDeleteI love learning about the author. It's always great to hear why they wrote something, their original intentions and their perspective on their characters. I will definitely add this book to my reading list. I am always looking to ad more period piece novels. Well Done!

ReplyDeleteThanks, I'm happy you liked the interview!

Delete