This first in a four-part series takes place in a scrupulously researched mid-10th century Ireland amid warring clans and Danish invaders. Subtitled “a medieval Christian romance,” Man of Sorrows centers several families and two different love stories, each of which is daring for its time and for the genre.

Mara, a fifteen-year-old shepherdess, receives divine visitations that predict the future (like her late mother’s demise) and direct her to marry a man who will “humble himself by the sign of the cross.” After she sees a sign that her proposed husband is her best friend Áine’s brother, Marcan, she knows she’ll have trouble convincing him: Marcan is a pious monk at the Cill Dálua community who transforms vellum into beautiful, illuminated manuscripts.

Because he thinks he unwittingly caused his mother’s and brother’s deaths, Marcan accepts the abbot’s harsh rule. His father, needing Marcan to tend flocks at home, had waited to give him to the church, as he was duty-bound to do with his firstborn, and Marcan feels God is punishing him for the delay. The second romance involves the cross-class relationship between Áine and Davan, nephew of Chief Cennedigh of the Dal Cais, in a subplot that offers multiple surprises.

In this short novel, Stroh proficiently interweaves multiple viewpoints and plot threads without losing the reader’s attention. The characters and their religious beliefs feel period-appropriate. Mara’s steadfastness is admirable, and Marcan’s internal pain is evident as he struggles to determine God’s purpose for his life. The writing style ranges from smooth to overly formal and cumbersome (“I exist but to guard his means so that he might dote upon you”). The novel also needs a stronger copyedit. With the trials they undergo, Mara and Marcan deserve a happy ending, and it’s rewarding to see how they achieve it.

Man of Sorrows was published by Olivia Kimbrell Press in 2022; I wrote this review for the Historical Novels Review's August 2023 issue. The next three books in the series, which feature different characters from this book and are set two decades later, in the 960s, are Rise of Betrayal, Lord of Vengeance, and Stone of Division. Cill Dálua is now known as Killaloe, a town and parish in County Clare.

Thursday, August 31, 2023

Saturday, August 26, 2023

The Island of Doves sweeps readers away to historic Mackinac Island

My father’s family are Michiganders, going back to the state’s rustic pioneer days in the mid-19th century. When I was growing up, we spent many summer weeks visiting my grandmother and other relatives, and some of these excursions involved trips to Mackinac (pronounced “Mackinaw”) Island, a picturesque isle sitting in the middle of Lake Huron, between Michigan’s Lower and Upper Peninsulas. The romantic time-travel film Somewhere in Time, set in 1912 and decades later, took place there.

Kelly O’Connor McNees’ The Island of Doves is also set on Mackinac, quite a bit earlier – in the 1830s, when the small piece of land was loosely populated by Odawa Indians, French settlers and traders, Métis families who were the descendants of both, and white Presbyterians relocating to Michigan from the east. One of its main attractions are the beautiful images of Mackinac’s unspoiled wilderness and waterscapes, and the depictions of life on the frontier: tending gardens, producing maple syrup, sewing moccasins, traveling by sled dog and canoe.

McNees’ two heroines are easy to warm to. As the wife of one of Buffalo’s leading business moguls, Susannah Fraser has no material wants. Her husband Edward is physically and emotionally abusive, though, and Susannah, being a proud woman, tries to endure the pain on her own, preferring to spend her days tending plants in her greenhouse. Magdelaine Fonteneau, an adventurous widow in her forties of part-Odawa, part-French heritage, lives permanently on Mackinac but has amassed a small fortune as a fur trader. Having lost both her younger and older sisters decades earlier – in particular, young Josette had been killed by a jealous suitor – she opens her home to Susannah when she needs a safe haven. Susannah’s maid and a kindly nun in Buffalo arrange for her escape via steamboat. The trials on the voyage force Susannah (who now uses the last name Dove) to confront life’s unsavory side but also go far in teaching her self-sufficiency.

The plot centers on relationships and character growth, as Susannah gains independence and Magdelaine learns to accept that her adult son, Jean-Henri, has a calmer personality than that of his ambitious, risk-taking late father. The story dwells more on religious differences, particularly those between Protestants and Catholics, than race relations at the time. I had hoped for something deeper in that respect. The story is rewarding, though, with the writing as smooth and clear as the pristine waters near Magdelaine’s home. It’s a pleasant journey into a little-known aspect of America’s past. The author’s notes reveal that Magdelaine is closely based on a historical figure, and her story is also worth knowing.

The Island of Doves was published by Berkley in 2014. I read this book (from my own collection) at the start of the pandemic, wrote a review, then got distracted and forgot I hadn’t posted it! So I thought I would do so now.

Kelly O’Connor McNees’ The Island of Doves is also set on Mackinac, quite a bit earlier – in the 1830s, when the small piece of land was loosely populated by Odawa Indians, French settlers and traders, Métis families who were the descendants of both, and white Presbyterians relocating to Michigan from the east. One of its main attractions are the beautiful images of Mackinac’s unspoiled wilderness and waterscapes, and the depictions of life on the frontier: tending gardens, producing maple syrup, sewing moccasins, traveling by sled dog and canoe.

McNees’ two heroines are easy to warm to. As the wife of one of Buffalo’s leading business moguls, Susannah Fraser has no material wants. Her husband Edward is physically and emotionally abusive, though, and Susannah, being a proud woman, tries to endure the pain on her own, preferring to spend her days tending plants in her greenhouse. Magdelaine Fonteneau, an adventurous widow in her forties of part-Odawa, part-French heritage, lives permanently on Mackinac but has amassed a small fortune as a fur trader. Having lost both her younger and older sisters decades earlier – in particular, young Josette had been killed by a jealous suitor – she opens her home to Susannah when she needs a safe haven. Susannah’s maid and a kindly nun in Buffalo arrange for her escape via steamboat. The trials on the voyage force Susannah (who now uses the last name Dove) to confront life’s unsavory side but also go far in teaching her self-sufficiency.

The plot centers on relationships and character growth, as Susannah gains independence and Magdelaine learns to accept that her adult son, Jean-Henri, has a calmer personality than that of his ambitious, risk-taking late father. The story dwells more on religious differences, particularly those between Protestants and Catholics, than race relations at the time. I had hoped for something deeper in that respect. The story is rewarding, though, with the writing as smooth and clear as the pristine waters near Magdelaine’s home. It’s a pleasant journey into a little-known aspect of America’s past. The author’s notes reveal that Magdelaine is closely based on a historical figure, and her story is also worth knowing.

The Island of Doves was published by Berkley in 2014. I read this book (from my own collection) at the start of the pandemic, wrote a review, then got distracted and forgot I hadn’t posted it! So I thought I would do so now.

Saturday, August 19, 2023

Alys Clare's mystery The Cargo from Neira leads its physician protagonist into the 17th-century spice trade

The bustling, cutthroat spice trade forms the enticing backdrop for the fifth volume in Clare’s mystery series featuring country doctor Gabriel Taverner in early 17th-century Devon. If you haven’t read the previous four books, no need to worry, since it stands alone well. Banda Neira, the place of the title, is a remote Indonesian island that was the world’s main source for nutmeg, a spice in high demand in Europe for its food preservation and reputed medicinal properties.

In February 1605, Gabriel gets drawn into a mystery when the coroner’s manservant fetches him to view a body on the banks of the river Tavy, with the hopes he’ll conceal it was a suicide since these victims would be damned for eternity and their family penalized. The poor soul is a woman, single and six months pregnant, which could explain her desperate circumstances.

To Gabriel’s shock, the woman soon revives. Gabriel tends to her at Rosewyke, his home, but she’s petrified, unhappy to be alive, and unwilling to talk. Then a second body, a man’s, turns up in a cesspit in a seedy quayside alley of Plymouth with several costly nutmegs in his mouth. Gabriel feels the two incidents must be connected, especially after an attempted break-in at Rosewyke that terrifies his patient and gets him firmly into sleuthing mode.

The principal cast are a congenial bunch whose close-knit relationships contrast nicely with the danger stalking them. Gabriel’s sister, Celia, is a sharp-witted young widow, while housekeeper Sallie prepares comforting meals at a moment’s notice. Most intriguing are the changes within Gabriel as his investigation proceeds. A former ship’s surgeon now living shoreside after an injury, he starts feeling a strong pull to return. While abrupt, the viewpoint switches prove enlightening, and the mystery’s resolution, which offers surprises for Gabriel and the reader, is admirably well-plotted.

The Cargo from Neira was published in May by Severn House, and this review also appears on the Historical Novel Society website. I'm looking forward to reading both the earlier volumes in this series, and later ones as they appear.

In February 1605, Gabriel gets drawn into a mystery when the coroner’s manservant fetches him to view a body on the banks of the river Tavy, with the hopes he’ll conceal it was a suicide since these victims would be damned for eternity and their family penalized. The poor soul is a woman, single and six months pregnant, which could explain her desperate circumstances.

To Gabriel’s shock, the woman soon revives. Gabriel tends to her at Rosewyke, his home, but she’s petrified, unhappy to be alive, and unwilling to talk. Then a second body, a man’s, turns up in a cesspit in a seedy quayside alley of Plymouth with several costly nutmegs in his mouth. Gabriel feels the two incidents must be connected, especially after an attempted break-in at Rosewyke that terrifies his patient and gets him firmly into sleuthing mode.

The principal cast are a congenial bunch whose close-knit relationships contrast nicely with the danger stalking them. Gabriel’s sister, Celia, is a sharp-witted young widow, while housekeeper Sallie prepares comforting meals at a moment’s notice. Most intriguing are the changes within Gabriel as his investigation proceeds. A former ship’s surgeon now living shoreside after an injury, he starts feeling a strong pull to return. While abrupt, the viewpoint switches prove enlightening, and the mystery’s resolution, which offers surprises for Gabriel and the reader, is admirably well-plotted.

The Cargo from Neira was published in May by Severn House, and this review also appears on the Historical Novel Society website. I'm looking forward to reading both the earlier volumes in this series, and later ones as they appear.

Wednesday, August 16, 2023

How I wrote a true story as a novel, a guest post by Julia Park Tracey, author of The Bereaved

Historical fiction and historical nonfiction are interrelated and can be based on the same material. But when an author gets an idea for a new project, how do they decide which route to take? Read about Julia Park Tracey's experience below, and many thanks to the author for her thought-provoking essay!

~

How I Wrote a True Story as a Novel

Julia Park Tracey

I first started writing The Bereaved (a novel) as nonfiction. I'm a journalist by trade, and that means I look for facts and figures and actual quotes and information. I had just finished editing the second of two books called The Doris Diaries, about a teenager flapper in the Roaring Twenties. They were my great aunt’s diaries that I had inherited after she died. I had done a ton of background research, everything from teenagers in society, what were they eating and drinking, cars and technology, social upheaval, medical practices, clothes and fashion, and so on. I wrote a long introduction, several appendices, and indexed both books.

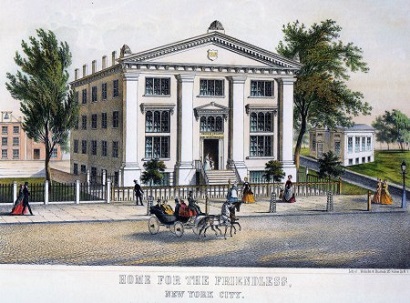

As a journalist and a part-time scholar of women’s history, I fully intended to take the story of The Bereaved—the true story of my third great grandmother and how she lost four of her children to the Orphan Trains, and how she tried to get them back—and tell it as nonfiction. In fact, I was excited at becoming known as a writer of women's history and telling untold stories.

I knew all of the facts of this story. But I wasn't quite sure how I was going to tell it. I laid it out chronologically and looked at the details, and I read several books of creative nonfiction about historical events. I took my outline with me to the Community of Writers at the Olympic Valley in Lake Tahoe and shared it with my group. The other writers gave me a lot of great ideas—for how to write a novel. So did the male leader of my group in my one-on-one meeting.

I was outraged. Are they saying that women should write novels instead of serious history? I spent a lot of time in the next two months raging internally about the misogyny inherent in that idea. But at the same time, I wanted to know what it was like to be Martha Seybolt Lozier.

So I bought some fabric and I bought a pattern for a Civil War dress; I cut it out and started sewing by hand. I sat in that wicker chair by the window and stitched lace and facings and top-stitched. I continued my hand sewing, between bouts of further research into her days and her era, while thinking about Martha and her children.

And as I sewed, I started thinking about all the things that Martha knew.

She knew how a pound of butter felt in the hand. How an old hen’s pulse beat against her fingers before she twisted its neck. How the feathers made a thin wet pop as she pulled them from the cooling skin.

That was the first paragraph that I wrote: Some of the things that Martha would know from living on a farm. And I knew that the language of living on a farm was what informed her character. I kept hearing Martha in my thoughts—what she might think about things and what she might have to do.

Managing the eggs: They need to be wiped but not washed. They’ll keep for weeks, but store them away from onions, fish, the smokehouse.

Ducks rose from the water loud with their honking voices, their clumsy splashing, the rapid beat of wings. How did Canada geese make flight so graceful, while ducks just seemed late and worried and fatigued? Like herself.

I kept writing what I was thinking about. And then when November rolled around and it was time for NaNoWriMo, I took advantage of the thirty days of enforced writing and coughed up a 50,000-word draft. Later, I went back through and wrote it again, adding another 40,000 words. Martha took shape, and so did her children, and so, too, The Bereaved.

Instead of writing in a journalistic style, I was writing a close third person, telling Martha’s story and (gasp) filling in the details that I imagined, that I invented: The color of her hair, her eyes. Her relationship with her in-laws. The terrible thing that made her flee from the farm. And so on—breaking the sacred journalism rule that Everything Must Be True.

I reality, there are many facts I don’t know about Martha. I have not yet seen a photo, if any exist. I found her burial site but not when she died. I have seen her signature but I don’t know her voice or anything she might have said directly. All of my quotes are imagined.

For a journalist like me, that was hard to do—but Martha and her story are worth it.

The Bereaved: A Novel—Historical fiction by Julia Park Tracey; Sibylline Press, August 2023; 270 pages; ISBN 9781736795422. $18.

Julia Park Tracey, a journalist of 40 years, is the author of seven books. Her latest is The Bereaved, historical fiction about a destitute widow who takes her children to an aid society in New York City for safekeeping, but the agency sends them out on the Orphan Train, and the bereaved mother must find her children again (based on the story of her third great grandmother). Find her online, any platform, @juliaparktracey.

Sunday, August 13, 2023

Mona Susan Power's A Council of Dolls evokes Dakota women's survival across three generations

Power, an enrolled Standing Rock Sioux tribal member, has penned an original saga detailing how forced colonization impacts three generations of Dakhóta women. She writes sensitively from each young protagonist’s viewpoint while also showing how their childhood ordeals affect them and their families over time.

In the 1960s, Sissy grows up in Chicago with her loving father and troubled mother, Lillian. We then learn Lillian’s history in 1930s North Dakota as she and her sister, Blanche, are sent to an Indian boarding school in Bismarck, where their cruel assimilation into white culture leads to a tragedy Lillian can’t recover from. In the 1900s, Lillian’s mother, Cora, travels to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania and survives the attempted stripping of her heritage.

Each girl has a doll who feels fully alive to her, serving as her confidant and protector. The final account, where an adult Sissy analyzes the dolls’ roles, processes her ancestors’ pain, and reclaims their power is beautifully healing and hopeful. This heart-wrenching account of inherited trauma and resilience is perceptively told.

A Council of Dolls was published by Mariner/HarperCollins on August 8; I wrote this review for Booklist. Not easy to encapsulate four separate stories into a 175-word review! There's much I had to leave out or only hint at. As Susan Power, the author has also written several other novels, including The Grass Dancer (1997), a saga spanning generations that's set on a reservation in North Dakota and likewise reflects her Sioux heritage.

In the 1960s, Sissy grows up in Chicago with her loving father and troubled mother, Lillian. We then learn Lillian’s history in 1930s North Dakota as she and her sister, Blanche, are sent to an Indian boarding school in Bismarck, where their cruel assimilation into white culture leads to a tragedy Lillian can’t recover from. In the 1900s, Lillian’s mother, Cora, travels to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania and survives the attempted stripping of her heritage.

Each girl has a doll who feels fully alive to her, serving as her confidant and protector. The final account, where an adult Sissy analyzes the dolls’ roles, processes her ancestors’ pain, and reclaims their power is beautifully healing and hopeful. This heart-wrenching account of inherited trauma and resilience is perceptively told.

A Council of Dolls was published by Mariner/HarperCollins on August 8; I wrote this review for Booklist. Not easy to encapsulate four separate stories into a 175-word review! There's much I had to leave out or only hint at. As Susan Power, the author has also written several other novels, including The Grass Dancer (1997), a saga spanning generations that's set on a reservation in North Dakota and likewise reflects her Sioux heritage.

Tuesday, August 08, 2023

Isabel Allende's The Wind Knows My Name draws parallels between stories of child migrants in modern history

In her compassionate novel, Allende draws powerful parallels between child migrants in 1938 Austria and at America’s southern border in 2019, evoking the tragic universality of war’s innocent young victims.

Samuel Adler is only five when his desperate mother, her home and world destroyed during Kristallnacht in Vienna, places him on a Kindertransport train to England. The antisemitic violence his family experiences feels visceral and immediate on the page.

Decades later, in 1981, Leticia Cordero arrives in the United States with her father, the sole survivors of their immediate family after a massacre in their El Salvadoran village. Later, in 2019, seven-year-old Anita Díaz and her mother, Marisol, are victims of the Trump administration’s family separation policies after they cross from Mexico into Arizona, fleeing a threatening home environment in El Salvador.

All these stories converge during the pandemic, starting when social worker Selena Durán gets lawyer Frank Angileri to take Anita’s case pro bono and help reunite her with Marisol, who may have been deported. By then, Samuel is an 86-year-old widower in San Francisco, and if anyone can relate to Anita’s plight firsthand, he can.

Frank’s rapid transformation from suave would-be seducer (he finds Selena very attractive) to conscientious human rights defender is too convenient, and their conversations about immigration policies seem designed to feed readers background information. But all the viewpoints alternate smoothly, and Allende has a particularly delicate touch in depicting children.

Samuel’s journey from Austria to England to America intertwines with his love for music, while young Anita, who is blind, retreats into an imaginary world to cope. Not only does Allende depict the heroic acts people undertake to help underage migrants, but she underscores the courage of those who do so at great risk to themselves.

The Wind Knows My Name was published by Ballantine (US/Can) and Bloomsbury (UK/Australia). It was translated into English by Frances Riddle. This review was cross-posted to the Historical Novel Society's website.

Samuel Adler is only five when his desperate mother, her home and world destroyed during Kristallnacht in Vienna, places him on a Kindertransport train to England. The antisemitic violence his family experiences feels visceral and immediate on the page.

Decades later, in 1981, Leticia Cordero arrives in the United States with her father, the sole survivors of their immediate family after a massacre in their El Salvadoran village. Later, in 2019, seven-year-old Anita Díaz and her mother, Marisol, are victims of the Trump administration’s family separation policies after they cross from Mexico into Arizona, fleeing a threatening home environment in El Salvador.

All these stories converge during the pandemic, starting when social worker Selena Durán gets lawyer Frank Angileri to take Anita’s case pro bono and help reunite her with Marisol, who may have been deported. By then, Samuel is an 86-year-old widower in San Francisco, and if anyone can relate to Anita’s plight firsthand, he can.

Frank’s rapid transformation from suave would-be seducer (he finds Selena very attractive) to conscientious human rights defender is too convenient, and their conversations about immigration policies seem designed to feed readers background information. But all the viewpoints alternate smoothly, and Allende has a particularly delicate touch in depicting children.

Samuel’s journey from Austria to England to America intertwines with his love for music, while young Anita, who is blind, retreats into an imaginary world to cope. Not only does Allende depict the heroic acts people undertake to help underage migrants, but she underscores the courage of those who do so at great risk to themselves.

The Wind Knows My Name was published by Ballantine (US/Can) and Bloomsbury (UK/Australia). It was translated into English by Frances Riddle. This review was cross-posted to the Historical Novel Society's website.

Wednesday, August 02, 2023

The View from Half Dome, set in the 1930s, evokes the splendor of Yosemite National Park

This lovely tale of coming-of-age and intergenerational friendship takes place against the spectacular natural backdrop of Yosemite National Park during the Depression.

Isabel Dickinson’s dreary life provokes immediate empathy: just sixteen in 1934, she attends high school, cooks, cleans her dingy San Francisco apartment, and watches over her nine-year-old sister while her overworked mother struggles to support the family after Isabel’s dad’s unexpected death. Isabel envies the freedom of her older brother, James, who took a job with the CCC at Yosemite and sends money back to help them pay bills.

After Isabel’s attempt to claim some personal independence ends terribly, she asks a friend to drive her the long distance to James’s campsite, desperate for a new start. This creates some awkwardness – the CCC doesn’t permit visitors – but Enid Michael, the park’s only female ranger and naturalist, offers her a room in the small apartment she shares with her husband, the assistant postmaster.

Enid, a historical figure, led an extraordinary life cultivating Yosemite’s public wildflower garden, writing countless articles about the park that shaped its public perception, and leading popular tourist walks, all under the eye of a sexist supervisor who looked for excuses to fire her. In this novel, Enid’s in her early fifties, an active mountain-climber who shares her considerable knowledge with Isabel.

Enid’s personal story is so interesting that readers may find their attention drawn away from Isabel, but Caugherty sets up a good dynamic between them. While Isabel admires the older woman’s spirit and determination, she dislikes her habit of lavishing food on birds when people elsewhere are starving.

Isabel’s steady path to emotional maturity feels convincing, and the scenes evoking Yosemite’s beauty are poetically described and spiritually invigorating. Young adults will especially enjoy The View from Half Dome, and so will any reader who thirsts for the great outdoors.

This novel was published by Black Rose Writing in April, and I reviewed it for the Historical Novel Society, where it's cross-posted to the HNS website.

Read more about Enid Michael in an article from Backpacker: "The Story of Enid Michael, Yosemite's First Female Naturalist." I'm glad to have had the chance to meet her in the course of reading this novel. And if you'd like to travel-by-novel to Yosemite of nearly a century ago, you'd do well to pick up this book!

Isabel Dickinson’s dreary life provokes immediate empathy: just sixteen in 1934, she attends high school, cooks, cleans her dingy San Francisco apartment, and watches over her nine-year-old sister while her overworked mother struggles to support the family after Isabel’s dad’s unexpected death. Isabel envies the freedom of her older brother, James, who took a job with the CCC at Yosemite and sends money back to help them pay bills.

After Isabel’s attempt to claim some personal independence ends terribly, she asks a friend to drive her the long distance to James’s campsite, desperate for a new start. This creates some awkwardness – the CCC doesn’t permit visitors – but Enid Michael, the park’s only female ranger and naturalist, offers her a room in the small apartment she shares with her husband, the assistant postmaster.

Enid, a historical figure, led an extraordinary life cultivating Yosemite’s public wildflower garden, writing countless articles about the park that shaped its public perception, and leading popular tourist walks, all under the eye of a sexist supervisor who looked for excuses to fire her. In this novel, Enid’s in her early fifties, an active mountain-climber who shares her considerable knowledge with Isabel.

Enid’s personal story is so interesting that readers may find their attention drawn away from Isabel, but Caugherty sets up a good dynamic between them. While Isabel admires the older woman’s spirit and determination, she dislikes her habit of lavishing food on birds when people elsewhere are starving.

Isabel’s steady path to emotional maturity feels convincing, and the scenes evoking Yosemite’s beauty are poetically described and spiritually invigorating. Young adults will especially enjoy The View from Half Dome, and so will any reader who thirsts for the great outdoors.

This novel was published by Black Rose Writing in April, and I reviewed it for the Historical Novel Society, where it's cross-posted to the HNS website.

Read more about Enid Michael in an article from Backpacker: "The Story of Enid Michael, Yosemite's First Female Naturalist." I'm glad to have had the chance to meet her in the course of reading this novel. And if you'd like to travel-by-novel to Yosemite of nearly a century ago, you'd do well to pick up this book!