The Wars of the Roses between the Lancaster and York dynasties, and the fate of the Princes in the Tower, have been the subject of numerous historical novels. Each posits its own solution to this real-life mystery from 15th-century England, but the larger story has become well-known to readers of the genre. With her latest novel inspired by women from her family tree, Elizabeth St.John manages to shine an entirely new light on familiar happenings.

The author’s heroine – Lady Elysabeth (St.John) Scrope, who narrates – is someone who would have had a front-row seat to key events and was linked by blood, marriage, or promise to nearly all the major players. Yet I hadn’t heard of her. It feels like her story has been hiding in plain sight all these years, just waiting for someone to discover it. The Godmother’s Secret is a wonderful novel: well-paced, richly characterized, and infused with the author’s theme of how loyalties can influence choices and divide families.

The wife of Yorkist baron John “Jack” Scrope of Bolton Castle, Elysabeth is also the older half-sister of Lancastrian heiress Margaret Beaufort. In the year 1470, Henry VI, last king of the Lancastrian branch of the Plantagenets, asks Elysabeth to witness the birth of, and stand as godmother to, the newborn York heir, thus “placing a cuckoo in the York nest,” as Margaret puts it. Though wary of this undesired responsibility, Elysabeth takes her holy oath to safeguard young Ned's welfare very seriously, even as it sets her against family members and even her husband. Her narrative charts the complex, dangerous path that follows the rise and fall of Fortune’s wheel, as various individuals from the York and Lancaster contingents challenge one another, often with subterfuge, and seek ascendancy.

Besides Elysabeth herself, one of the few who holds the York princes’ welfare close to her heart, there are many other finely delineated characters. The incessant scheming of Margaret Beaufort, with her unique blend of piety and maternal ambition, proves incredibly vexing for her older sister. That said, Elysabeth feels protective towards Margaret, who was forced to marry too young and remains devoted to her only son, Henry Tudor. The love story between Elysabeth and husband Jack unfolds in a moving way, even as she weighs whether to assert her will and flout his wishes. This is also the rare story that fleshes out the personalities of the young princes, Ned and Dickon. The era was an uneasy time for royal children.

This epic novel moves quickly, though it’s worth slowing down to savor the language (“men may fight across hill and dale, but the women draw their own York and Lancaster battle lines across planked and herb-strewn chamber floors”). Elysabeth has multiple secrets to keep, including the Princes’ fate, but another is the existence of her own sovereynté – the agency to decide things for herself. Her determination to chart her own path underlies her actions in this well-researched and engrossing book.

The Godmother's Secret was published in October; thanks to the author for sending me a Kindle copy. See also my earlier reviews of the author's Lydiard Chronicles: The Lady in the Tower, By Love Divided, and Written in Their Stars.

Monday, November 28, 2022

Tuesday, November 22, 2022

Mademoiselle Revolution by Zoe Sivak presents the Haitian and French Revolutions from a new viewpoint

Sivak’s bold debut is an original take on the Haitian and French Revolutions, seen from the viewpoint of a biracial woman awakening to her privilege and learning how to wield it in liberty’s name.

In 1791, Sylvie de Rosiers, eighteen and beautiful, is the cosseted only daughter of a coffee planter in Saint-Domingue, a French colony in the West Indies. Her father’s status means she was born free, unlike the Black mother she never knew, and she disdains politics in favor of standard feminine pursuits. But the island’s enslaved people are rising in rebellion. After she sees Vincent Ogé executed for his racial justice activism, Sylvie realizes her complicity in the horrific system.

The action scenes are strikingly written as Sylvie and her half-brother Gaspard narrowly escape being killed and, eventually, sail to Paris, where they stay with their kindly aunt. Among their neighbors are the Duplay family and their soon-to-be-famous tenant, Maximilien Robespierre. As Sylvie’s mind expands through their conversations, she falls into an affair with Robespierre’s confidante and mistress, Cornélie Duplay, though admires Robespierre deeply and can’t get him off her mind.

It takes audacity to insert a fictional character amidst the French Revolution’s major players, but Sivak manages to pull it off. That said, Sylvie can be reckless—leaving the house in pearls with impoverished sans-culottes nearby isn’t the brightest move—and the prose occasionally lands heavily. The scope is impressively wide-ranging as Sylvie, from her unique vantage as a woman of color, observes the shifts between different political factions and realizes her power and its limitations.

Cinematic details unfold on the page as violent discord plays out on Paris’s streets and Sylvie ponders the similarities and differences between the two revolutions. Thought-provoking and passionate, this story marks Sivak as an author worth watching.

Mademoiselle Revolution was published by Berkley in August (I reviewed it for the Historical Novels Review, from a NetGalley copy).

In 1791, Sylvie de Rosiers, eighteen and beautiful, is the cosseted only daughter of a coffee planter in Saint-Domingue, a French colony in the West Indies. Her father’s status means she was born free, unlike the Black mother she never knew, and she disdains politics in favor of standard feminine pursuits. But the island’s enslaved people are rising in rebellion. After she sees Vincent Ogé executed for his racial justice activism, Sylvie realizes her complicity in the horrific system.

The action scenes are strikingly written as Sylvie and her half-brother Gaspard narrowly escape being killed and, eventually, sail to Paris, where they stay with their kindly aunt. Among their neighbors are the Duplay family and their soon-to-be-famous tenant, Maximilien Robespierre. As Sylvie’s mind expands through their conversations, she falls into an affair with Robespierre’s confidante and mistress, Cornélie Duplay, though admires Robespierre deeply and can’t get him off her mind.

It takes audacity to insert a fictional character amidst the French Revolution’s major players, but Sivak manages to pull it off. That said, Sylvie can be reckless—leaving the house in pearls with impoverished sans-culottes nearby isn’t the brightest move—and the prose occasionally lands heavily. The scope is impressively wide-ranging as Sylvie, from her unique vantage as a woman of color, observes the shifts between different political factions and realizes her power and its limitations.

Cinematic details unfold on the page as violent discord plays out on Paris’s streets and Sylvie ponders the similarities and differences between the two revolutions. Thought-provoking and passionate, this story marks Sivak as an author worth watching.

Mademoiselle Revolution was published by Berkley in August (I reviewed it for the Historical Novels Review, from a NetGalley copy).

Thursday, November 17, 2022

Historical novel showcase for University Press Week 2022, part 2

Here's the second half of the University Press Week celebration at Reading the Past, with nine other new and forthcoming historical novels (by seven authors) from a variety of university presses.

A story of local dramas and racism in a "sundown town" (where Black people were warned to stay away after dark) in rural Illinois in the 1960s, James Janko's What We Don't Talk About is out this month from the University of Wisconsin Press. (Published November 2022)

Code of Honor is the 16th novel in the Peter Wake nautical adventure series from award-winning novelist Robert N. Macomber. Over the past twenty years, the series has moved from small, Florida-based Pineapple Press to McBooks Press, a publisher of adventure fiction, and now to the Naval Institute Press. This latest entry follows Wake, now Rear Admiral after a decades-long career in the U.S. Navy, through the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05. (Published April 2022)

Mercer University Press in Macon, Georgia, publishes multiple historical novels each year. John Pruitt's Tell It True centers on the murder of a Black lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army reserve and the subsequent investigation, which pulls in the stories of journalists, politicians, the police, and more during a time of Civil Rights protests in summer 1964. (Published October 2022)

Laura Secord's An Art, a Craft, a Mystery is unusual for the genre is that it's a work of adult fiction written as poetry. It comes from Livingston Press, the literary imprint at the University of West Alabama. Set in mid-17th-century Connecticut, the novel reveals the little-known stories of two real-life women who were accused of witchcraft. (Published February 2022)

In terms of literary works, Stephen F. Austin State University (SFA) Press specializes in East Texas and regional settings. Anne Sloan's Her Choice features a female journalist covering the 1928 Democratic National Convention in Houston as the city attempts damage control after a lynching takes place there days before the crowds arrive. (Published November 2022)

The lives of early 20th-century residents of the Southwest also figure in C. W. Smith's Girl Flees Circus, about an aviatrix making a sudden appearance in a tiny New Mexican town, upending everyone's lives (and her own). From the University of New Mexico Press, which has an active fiction list and has also published juvenile fiction. (Published September 2022)

Norwegian-Danish novelist Sigrid Undset won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1928; her best-known work is her three-volume epic of a woman's tumultuous life in medieval Norway, Kristin Lavransdatter. Tiina Nunnally received acclaim for the modern translation. More recently, she took on the project of translating Undset's Olav Audunssøn saga, also set in 13th-century Norway. (The previous translation was published as The Master of Hestviken.) Details at the website of its publisher, the University of Minnesota Press, mention that their edition of Olav Audunssøn is the first English version of this series in nearly 100 years. The first three volumes have appeared so far. Read more at The Modern Novel website. (Published 2020-2022)

Monday, November 14, 2022

Celebrating University Press Week 2022 with a historical novel showcase (and resources for potential authors)

Happy University Press Week! Held this year on November 14-18, this annual celebration recognizes the excellence and innovations in university press publishing. The event is sponsored currently by the Association of University Presses, which revived it in 2012, meaning it's now in its 11th year.

Happy University Press Week! Held this year on November 14-18, this annual celebration recognizes the excellence and innovations in university press publishing. The event is sponsored currently by the Association of University Presses, which revived it in 2012, meaning it's now in its 11th year. University presses are known for publishing the latest in scholarly research via monographs and journals. Authors and readers may not realize, though, that many university presses are also active publishers of fiction for a general readership. The historical novels from these presses often have a regional focus or common theme, such as Western fiction or international fiction in English translation. That said, university presses don't chase the latest trends, so you'll find topics and settings treated here that may not be picked up by large commercial publishers. As such, they make an integral contribution to the historical fiction landscape.

Interested in considering a university press for your historical fiction manuscript? Please see Finding a Publisher at the AUP site, and look especially at the subject area grid to see which member presses publish fiction. You typically won't need a literary agent, but if you have one, they can assist with the process. Also see Who can be published by a university press? While authors of scholarly monographs may need a terminal degree, this varies by genre and doesn't usually apply to fiction.

Now on to the books! Below are eight new and upcoming historical novels from university presses. This is the first of two posts.

Hoopoe is the fiction imprint of the American University in Cairo Press, and they specialize in novels from the Middle East, especially works in translation. Ibrahim al-Koni's The Night Will Have Its Say, translated by Nancy Roberts, is set in the late seventh century CE amid the Arab conquests of North Africa. Read an interview with the author at the Hoopoe Fiction blog. (Published November 2022)

Bison Books, the trade imprint of the University of Nebraska Press, emphasizes literature of the "trans-Mississippi West." Kate Anger's debut The Shinnery, inspired by historical events, tells a coming-of-age story about a young woman in 1890s Texas who gets mixed up with the wrong man. (Published September 2022)

Native Oklahoman (and English professor at the University of Oklahoma) Rilla Askew went with the University of Oklahoma Press for publication of her newest historical novel, Prize for the Fire, biographical fiction about Tudor-era writer and preacher Anne Askew (no known relation), who was burned at the stake for heresy in 1546. The author's Depression-era historical novel Harpsong was published by the same press in 2007. Read her launch interview with Anne Easter Smith at the Historical Novel Society website. (Published October 2022)

Douglas Bauer's The Beckoning World, just out from the University of Iowa Press, tells the story of a coal miner who achieves his dream of playing major-league baseball in the early 20th century, against the background of the Spanish influenza pandemic. (Published November 2022)

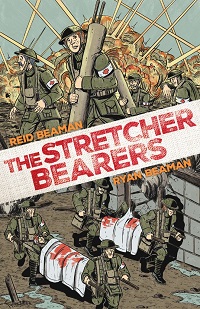

Dead Reckoning, the U.S. Naval Institute's graphic novel imprint, has been publishing military-themed historical fiction and nonfiction for several years. Read about the background to their publishing program at Publishers Weekly. The Stretcher Bearers by brothers Reid Beaman and Ryan Beaman centers on a group of young men who strive to save their fellow soldiers during WWI's Meuse-Argonne Offensive. (Published April 2022)

From the University of Virginia Press comes Crusoe's Footprint by Martinique-born French novelist Patrick Chamoiseau (trans. Jeffrey Landon Allen and Charly Verstraet), a novel that incorporates Creole history in its magical-realism retelling of the story of Daniel Defoe's character Robinson Crusoe. (Published November 2022)

Columbia University Press has published translations of many works of literature from Asia. Translated into English by Pao-fang Hsu, Ian Maxwell, and Tung-jung Chen, Puppet Flower by Yao-Chang Chen dramatizes the Rover incident of 1867, a political crisis ignited by the wreck of an American merchant ship in southern Taiwan and subsequent acts of retaliation, as seen from multiple viewpoints. (To be published April 2023)

Patricia L. Hudson's debut novel, Traces, reveals American frontier history from the viewpoints of Rebecca Boone, wife of Daniel, and two of their daughters, Susannah and Jemima, combining detailed historical research with logical supposition. Read more about it in the author's interview for The Southern Review of Books and in the Historical Novels Review's New Voices column. It was published by the University of Kentucky Press's Fireside Industries imprint, which focuses on stories of rural America and Appalachia. (Published November 2022)

Saturday, November 12, 2022

Review of Olesya Salnikova Gilmore's The Witch and the Tsar, myth-inspired historical fantasy set in 16th-century Russia

In the vein of Madeline Miller’s Circe and other feminist takes on long-enduring myths, Gilmore’s debut novel takes a fresh look at Baba Yaga, depicting her not as an evil hag but as a half-mortal woman who shoulders the burden of saving Russia’s people from tyranny and malevolent gods during Ivan the Terrible’s reign.

Daughter of Mokosh, an ancient earth goddess, Yaga is a skilled healer who helps clients who visit her hut in the remote Russian woods. Though centuries old, she appears no more than thirty and misses living in a community, but she’s learned her lesson about involving herself in human affairs. That is, until Anastasia Romanovna, the tsaritsa, calls upon their longtime friendship. Anastasia has been poisoned, and after healing her, Yaga returns to Moscow and the royal court to safeguard Anastasia’s life—and finds herself facing characters with whom she has a painful history, and who may be manipulating Tsar Ivan to their own dreadful purposes.

Set amid the political turmoil of 16th-century Russia, a woefully underutilized setting in fiction, The Witch and the Tsar incorporates impressive world-building—the necessary scaffolding for an immersive experience in both historical fiction and fantasy. The novel is about as ideal a crossover between the genres that it’s possible to achieve, with vivid details on colorful period clothing, palace décor, and the brooding taiga as well as otherworldly rituals and capricious divine beings. Though packed with bursts of action, the story is quite thoughtful and paced accordingly.

The overall tone is dark, though Yaga’s chicken-legged hut, Little Hen, is adorable and lightens the mood on occasion. Yaga can be overly naïve, given her true age and experience, though Gilmore succeeds in showing her emotional growth and the full range of her mortal and divine natures. This deep-dive into Russian history and folklore presents a rich cultural panorama.

The Witch and the Tsar was published by Berkley/Ace on September 20; I reviewed it for November's Historical Novels Review. The novel will be published in the UK by HarperVoyager in December.

Daughter of Mokosh, an ancient earth goddess, Yaga is a skilled healer who helps clients who visit her hut in the remote Russian woods. Though centuries old, she appears no more than thirty and misses living in a community, but she’s learned her lesson about involving herself in human affairs. That is, until Anastasia Romanovna, the tsaritsa, calls upon their longtime friendship. Anastasia has been poisoned, and after healing her, Yaga returns to Moscow and the royal court to safeguard Anastasia’s life—and finds herself facing characters with whom she has a painful history, and who may be manipulating Tsar Ivan to their own dreadful purposes.

Set amid the political turmoil of 16th-century Russia, a woefully underutilized setting in fiction, The Witch and the Tsar incorporates impressive world-building—the necessary scaffolding for an immersive experience in both historical fiction and fantasy. The novel is about as ideal a crossover between the genres that it’s possible to achieve, with vivid details on colorful period clothing, palace décor, and the brooding taiga as well as otherworldly rituals and capricious divine beings. Though packed with bursts of action, the story is quite thoughtful and paced accordingly.

The overall tone is dark, though Yaga’s chicken-legged hut, Little Hen, is adorable and lightens the mood on occasion. Yaga can be overly naïve, given her true age and experience, though Gilmore succeeds in showing her emotional growth and the full range of her mortal and divine natures. This deep-dive into Russian history and folklore presents a rich cultural panorama.

The Witch and the Tsar was published by Berkley/Ace on September 20; I reviewed it for November's Historical Novels Review. The novel will be published in the UK by HarperVoyager in December.

Tuesday, November 08, 2022

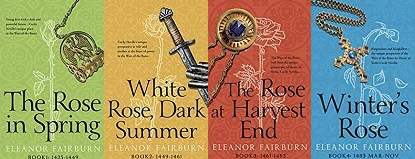

The historical novels of Irish writer Eleanor Fairburn are available again

Eleanor Fairburn (1928-2015), whose real name was Eva (Lyons) Fairburn, was a highly regarded historical novelist and mystery writer. She wrote under various pseudonyms; you can find a lengthy biography of her, with details on her work, at the National Museum of Ireland. Within the historical fiction genre, she specialized in re-creating the lives of medieval and Renaissance women who had unfairly been forgotten and whose actions were frequently deemed scandalous in their time.

Most of her historical novels were never published in the United States, and I only became aware of them because I'd been collecting fiction about royalty. Novels about royal women were in vogue in the UK in the 1960s-1980s, and among them, Fairburn's novels stand out for their deft portraits of complex heroines and the circumstances they lived through. The books weren't easy to find (many were published before I was born), and some never appeared on the secondhand market because they were so rare.

In 2010, I wrote a review of Fairburn's The Golden Hive for this blog, as part of one of the reading challenges that were so popular then. Its subject is Nesta of Deheubarth, an 11th-century Welsh noblewoman who became a mistress of England's King Henry I. The Golden Hive was published in 1966, and the writing still had a freshness that drew me in. If you follow Elizabeth Chadwick on social media, you'll know that she's also written a novel about Nesta (The King's Jewel) that will be out in April 2023, and I look forward to seeing her take on the character.

After my post went up, I was excited to get an email from the author herself. She thanked me for the review, said it was a nice surprise to find it, and that she was hoping to interest her publisher in reprinting. I wrote back that I hoped that would happen. Fast forward twelve years, and the other day I came upon new editions of Fairburn's novels on Amazon, published by the Fairburn Estate, with new introductions and beautifully designed covers. Thanks to the rise of indie publishing, more readers today will be able to easily obtain her books without going through used book dealers.

Their subjects are as follows. Links go to the Kindle editions, but they're also available in paperback.

The Cecily Quartet, photo at top, is a series of four novels about Cecily of York, mother of Edward IV and Richard III during England's War of the Roses, imagining her life from childhood through old age. The note on Amazon says the series was republished for its 50th anniversary.

Crowned Ermine reveals the life story of heiress Anne of Brittany, who became twice queen of France in the 15th century.

Fairburn's The Green Popinjays is about Lady Lucia de Thweng, termed the "Helen of Cleveland." The author's first historical novel, it delved into the life and motivations of a woman of notoriety from 13th-century Yorkshire who married three times, divorced one of her husbands, and had several children out of wedlock. Read more about Lucia at the Cleveland & Teesside Local History Society.

The White Seahorse covers the life of Graunya "Grace" O'Malley, Irish pirate queen during the Elizabethan era.

and The Golden Hive is detailed as above. Three of Fairburn's mysteries written as Catherine Carfax, with settings ranging from Victorian England to then-contemporary France and Ireland, are also newly available. If you decide to pick any of these up, please let me know your thoughts!

Sunday, November 06, 2022

Serena Burdick's The Stolen Book of Evelyn Aubrey tells a Victorian tale of family mystery and delicious revenge

If you could get back at someone who profoundly wronged you, even if it upends your life, would you do it? This is the question facing Evelyn Aubrey, a once-adored wife in turn-of-the-20th-century Oxfordshire, England. For her, the opportunity proves too seductive to resist.

In 1898, after ditching her stolid fiancé, Evelyn dives headlong into a passionate marriage with William Aubrey, a writer basking in the success of his recent debut novel. She expects their life at his ancestral home, Abbington Hall, to center on their shared literary interests—Evelyn is penning her own book—but a bout of writer’s block transforms William into a cold, jealous creature who steals her manuscript and publishes it under his own name.

Much later, in 2006 Berkeley, California, Abigail Phillips finds a photograph of her late mother with a young man—the father she knew nothing about—and learns he was the great-grandson of Evelyn Aubrey, a redhead with Gibson Girl looks who she strongly resembles. Abigail travels to England to learn about the mysterious Evelyn, who vanished the same day William’s scandalous final book was published.

As with many multi-period novels, the historical thread is the more compelling, with twists aplenty and a period-accurate theme of sexist double standards. “It still surprises him that I am his equal, and it surprises me that he would think of me as anything less,” writes Evelyn about her new husband in her journal—words that hit home.

To give her a deeper character arc, Burdick makes Abigail a directionless woman in her early thirties (she seems much younger), and Abbington Hall’s current residents accept her story with astonishing ease. Abigail’s journey toward maturity is ultimately touching, and the mystery of Evelyn’s fate unfolds in both timelines with growing suspense. This gothic-tinged novel tells an empowering tale of betrayal and delicious revenge.

The Stolen Book of Evelyn Aubrey was published by Park Row/HarperCollins in the US on November 1 (I reviewed it for November's Historical Novels Review).

In 1898, after ditching her stolid fiancé, Evelyn dives headlong into a passionate marriage with William Aubrey, a writer basking in the success of his recent debut novel. She expects their life at his ancestral home, Abbington Hall, to center on their shared literary interests—Evelyn is penning her own book—but a bout of writer’s block transforms William into a cold, jealous creature who steals her manuscript and publishes it under his own name.

Much later, in 2006 Berkeley, California, Abigail Phillips finds a photograph of her late mother with a young man—the father she knew nothing about—and learns he was the great-grandson of Evelyn Aubrey, a redhead with Gibson Girl looks who she strongly resembles. Abigail travels to England to learn about the mysterious Evelyn, who vanished the same day William’s scandalous final book was published.

As with many multi-period novels, the historical thread is the more compelling, with twists aplenty and a period-accurate theme of sexist double standards. “It still surprises him that I am his equal, and it surprises me that he would think of me as anything less,” writes Evelyn about her new husband in her journal—words that hit home.

To give her a deeper character arc, Burdick makes Abigail a directionless woman in her early thirties (she seems much younger), and Abbington Hall’s current residents accept her story with astonishing ease. Abigail’s journey toward maturity is ultimately touching, and the mystery of Evelyn’s fate unfolds in both timelines with growing suspense. This gothic-tinged novel tells an empowering tale of betrayal and delicious revenge.

The Stolen Book of Evelyn Aubrey was published by Park Row/HarperCollins in the US on November 1 (I reviewed it for November's Historical Novels Review).

Tuesday, November 01, 2022

Gill Hornby's Godmersham Park takes a witty, observant look at Jane Austen's family

Within the umbrella of historical fiction, one finds the category of biographical novels, works re-imagining the stories of real-life people from the past. Gill Hornby’s Godmersham Park, centering on a woman who worked for Jane Austen's family, ranks among the best of them.

Hornby’s protagonist is Anne Sharp, who arrives at the comfortable estate of Godmersham Park in rural Kent in 1804 to become governess to Fanny Austen, eldest daughter of Jane’s brother Edward. Anne is brand new to this role; she was raised as the beloved only daughter of a respectable man who mysteriously cast her off after her mother’s death, leaving her only a small annual income of £35. (We learn why as the novel progresses. Although little is known of the historical Anne Sharp’s background, Hornby makes a logical guess at the reason.)

Perplexed by her unexpected circumstances, Anne, aged 31, needs to walk a fine line with her exacting new mistress, Elizabeth Austen. “Miss Sharp” must be intelligent but not too clever; she must be proper and respectable without attracting male attention. Most of all, she should avoid all excesses, including – ironically – any enthusiasm for female education: “You are not here to turn my daughter into a bluestocking,” Mrs. Austen tells her. “Oh, but of course—” she replies, though we learn that “Anne could think of little else finer.”

Although Anne must tamp down her passionate nature with the large Austen brood – as Fanny informs her, new babies arrive with regularity – Hornby brings Anne’s complex persona alive for readers, who can delight in the keen observations and wry remarks she isn’t allowed to speak aloud. Anne’s status as not-quite-family, not-quite-servant makes her an outsider in nearly all respects, which gives her a uniquely perceptive viewpoint on household goings-on. As a boy, Edward Austen had the advantage of being adopted by wealthy distant relatives, and his fortune, when compared to his siblings, creates an unbridgeable divide that Hornby describes with crisp, elegant detail: “The Austens, she now saw, were of the same family and yet two distinct classes. She was witnessing here both sides of the fairy tale.”

As governess, “Miss Sharp” faces other challenges. She is plagued by severe headaches, and the below-stairs servants hate her, but she can’t risk losing her position by complaining about either. On his visits, Henry Austen, Edward’s brother, poses difficulty as well. He recognizes Anne’s intelligence, and she’s alternately vexed and intrigued by his combination of clueless male privilege and thoughtful kindness. Through Fanny’s correspondence with her Aunt Jane, Anne comes to feel an affinity for this Austen relation, which develops into firm friendship when the women meet in person. And while Jane plays a major role later in the story, she doesn’t steal the spotlight. Anne is such a vibrant character that she more than holds her own.

Brimming with the perennial Austen themes of social class and the precariousness of women’s financial situations, Godmersham Park presents a richly evoked Georgian atmosphere, nuanced family dynamics, and numerous quotable lines of witty dialogue. The novel is a treasure for all lovers of character-centered historical fiction, both Austen devotees and not.

Godmersham Park is published in the U.S. by Pegasus Books today, and this review is part of the author's blog tour with Austenprose PR.

Hornby’s protagonist is Anne Sharp, who arrives at the comfortable estate of Godmersham Park in rural Kent in 1804 to become governess to Fanny Austen, eldest daughter of Jane’s brother Edward. Anne is brand new to this role; she was raised as the beloved only daughter of a respectable man who mysteriously cast her off after her mother’s death, leaving her only a small annual income of £35. (We learn why as the novel progresses. Although little is known of the historical Anne Sharp’s background, Hornby makes a logical guess at the reason.)

Perplexed by her unexpected circumstances, Anne, aged 31, needs to walk a fine line with her exacting new mistress, Elizabeth Austen. “Miss Sharp” must be intelligent but not too clever; she must be proper and respectable without attracting male attention. Most of all, she should avoid all excesses, including – ironically – any enthusiasm for female education: “You are not here to turn my daughter into a bluestocking,” Mrs. Austen tells her. “Oh, but of course—” she replies, though we learn that “Anne could think of little else finer.”

Although Anne must tamp down her passionate nature with the large Austen brood – as Fanny informs her, new babies arrive with regularity – Hornby brings Anne’s complex persona alive for readers, who can delight in the keen observations and wry remarks she isn’t allowed to speak aloud. Anne’s status as not-quite-family, not-quite-servant makes her an outsider in nearly all respects, which gives her a uniquely perceptive viewpoint on household goings-on. As a boy, Edward Austen had the advantage of being adopted by wealthy distant relatives, and his fortune, when compared to his siblings, creates an unbridgeable divide that Hornby describes with crisp, elegant detail: “The Austens, she now saw, were of the same family and yet two distinct classes. She was witnessing here both sides of the fairy tale.”

|

| author Gill Hornby |

Brimming with the perennial Austen themes of social class and the precariousness of women’s financial situations, Godmersham Park presents a richly evoked Georgian atmosphere, nuanced family dynamics, and numerous quotable lines of witty dialogue. The novel is a treasure for all lovers of character-centered historical fiction, both Austen devotees and not.

Godmersham Park is published in the U.S. by Pegasus Books today, and this review is part of the author's blog tour with Austenprose PR.

PURCHASE LINKS

AMAZON | BARNES

& NOBLE | BOOK

DEPOSITORY | BOOKSHOP | GOODREADS

AUTHOR BIO

Gill Hornby is the author of the novels Miss Austen, The Hive, and All Together Now, as well as The Story of Jane Austen, a biography of Austen for young readers. She lives in Kintbury, England, with her husband and their four children.

TWITTER | FACEBOOK | BOOKBUB | GOODREADS